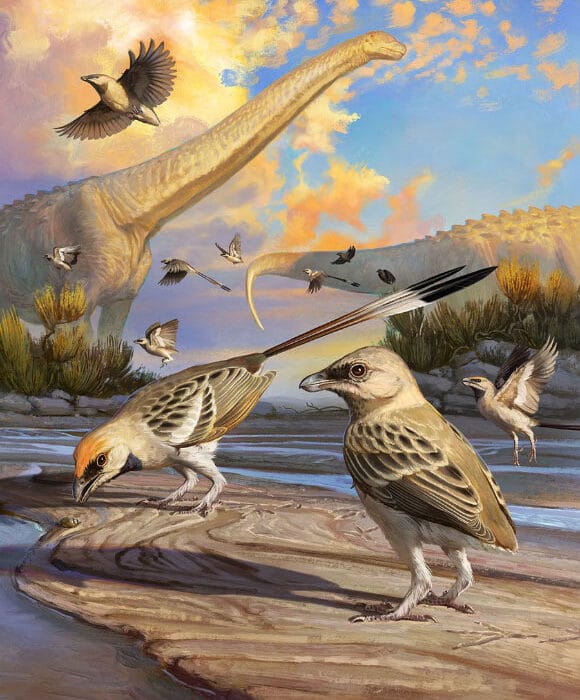

Sixty-six million years ago, the world ended in fire—and then in darkness. An asteroid six miles wide slammed into Earth near what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, releasing energy so immense that it shattered continents, blackened skies, and drove three out of every four species into extinction. Dinosaurs vanished. Giant marine reptiles sank into oblivion. The skies emptied of pterosaurs. But somehow, quietly, improbably, a small and unassuming lineage of lizards lived on.

Today, their descendants are called night lizards—members of the family Xantusiidae—and a new study from Yale University reveals that they not only survived the mass extinction that ended the Age of Dinosaurs, but did so with a set of traits that defy the established rules of survival.

Published in Biology Letters, this study is a story of evolutionary endurance that challenges what scientists thought they knew about mass extinctions—and offers urgent insights into our rapidly changing world.

When the World Burned and Froze

To appreciate the night lizards’ resilience, you must first understand what they survived.

Before the asteroid struck, Earth was lush and teeming. Forests flourished from pole to equator, and dinosaurs dominated every terrestrial niche. Mammals were still small and shadowy. Then came the Chicxulub impact—a cosmic bullet traveling over 43,000 miles per hour.

Within seconds, the planet changed forever. The collision carved a crater over 100 miles wide and 12 miles deep. A firestorm ignited across a thousand-mile radius. Waves taller than skyscrapers slammed coastlines. Superheated debris ejected into orbit returned like a meteor shower, raining molten rock across the planet and igniting wildfires that engulfed entire ecosystems.

But that was only the beginning.

In the following weeks, dust, soot, and chemicals filled the atmosphere, cutting off sunlight and plunging Earth into a cold, dim twilight—an “impact winter” that lasted months or years. Photosynthesis collapsed. Food chains crumbled. Acid rain poisoned oceans already deprived of oxygen. By the time it was over, 75% of all species were gone. The Age of Dinosaurs had ended.

Yet deep in some forgotten corner of the prehistoric landscape, night lizards endured.

An Unlikely Survivor Emerges

The Yale-led team, spearheaded by ecologists and evolutionary biologists, sought to answer a question that has haunted paleontology for decades: how did some species make it through while so many others perished?

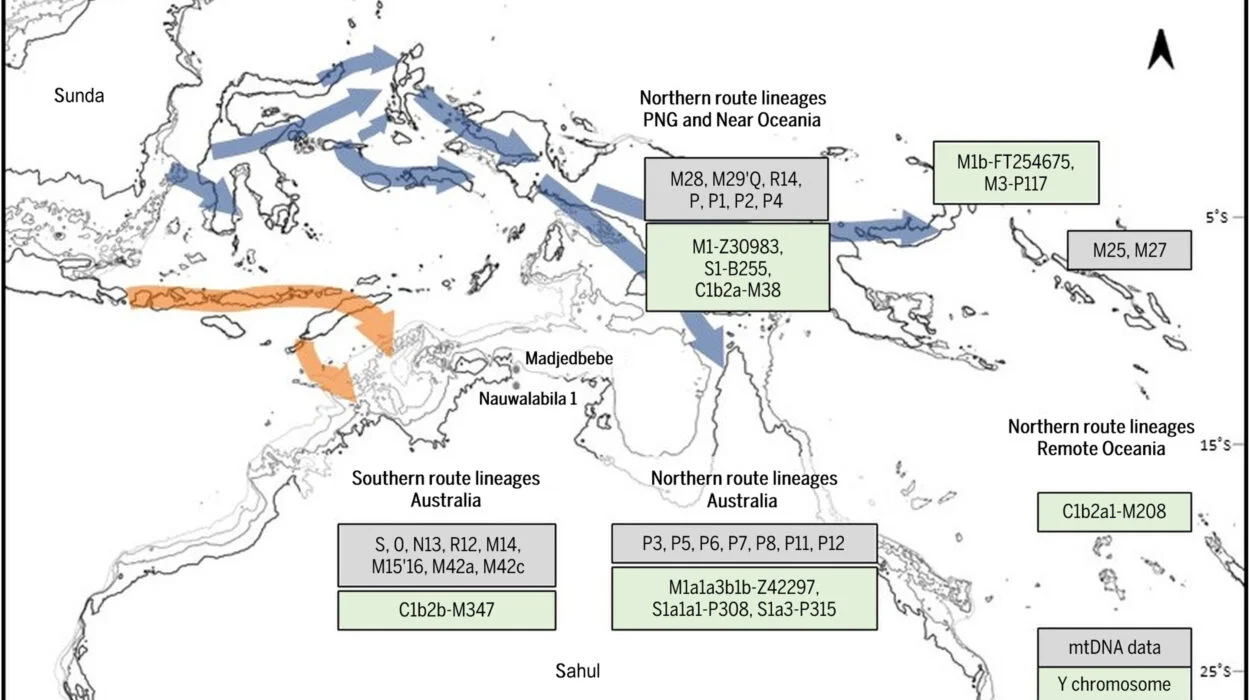

Using advanced phylogenetic “tip-dating” techniques—where DNA data from living species is combined with dated fossils—the researchers traced the family tree of Xantusiidae. Fossil records from the Early Cretaceous to the Miocene across North America and the Caribbean helped anchor the evolutionary timeline.

What they found was astonishing. The 34 living species of night lizards all descend from at least two ancestral lineages that were already thriving 92 million years ago—long before the asteroid fell. That places their survival squarely across the K-Pg boundary, making them one of the rare reptilian lineages to do so.

But what makes this survival even more remarkable is how they did it.

Breaking the Rules of Extinction

Conventional wisdom says that in times of catastrophic upheaval, survival favors species that are widespread, highly mobile, and fast-reproducing. Birds and mammals, for example, tend to recover more rapidly thanks to their larger geographic ranges and high reproductive rates.

Night lizards, by contrast, break every one of those rules.

They’re secretive and slow-moving. Many species inhabit narrow ecological niches, like rock crevices or arid island habitats. And they produce extremely small litters—often just one or two offspring per reproductive cycle. Some, like Cricosaura typica from Cuba, lay a single egg at a time.

Yet these traits, rather than dooming the night lizards, may have helped them persist.

Their isolated microhabitats could have sheltered them from the worst of the fires and atmospheric fallout. Their slow metabolism may have allowed them to survive longer on limited resources. And their sedentary, cryptic lifestyle may have made them less vulnerable to the initial shockwaves of extinction.

“Survival did not depend on broad geographic ranges or large broods,” the authors note. “Instead, night lizards appear to have crossed the extinction threshold while occupying narrow habitats and producing very few offspring.”

Echoes from a Lost World

Genetic clocks pointed to Cricosaura typica as the earliest offshoot of the family, diverging before its North and Central American cousins. Other species, like those from the genera Lepidophyma and Xantusia, didn’t diversify until about 12 million years ago—long after the asteroid’s dust had settled.

On California’s Channel Islands, a giant species of night lizard evolved from mainland ancestors that likely crossed temporary land bridges about 10 million years ago. There, isolated from predators and enriched by new resources, they grew larger and more prolific.

But across the board, the pattern held: night lizards survived not by expanding, but by holding tight to what they had. And then, over millions of years, they slowly adapted to new landscapes shaped by disaster.

A Front-Row Seat to Armageddon

Although no direct fossil evidence places night lizards at ground zero in the Yucatán during the impact, molecular dating suggests their ancestors lived in what is now North and Central America—geographically close to the Chicxulub site.

That proximity, combined with their ancient origins, suggests that these lizards didn’t just survive the extinction event—they witnessed it.

Imagine it: a small, scaly creature nestled in a burrow or beneath a boulder, feeling the Earth tremble as a city-sized asteroid strikes nearby. Ash darkens the sky. Plants vanish. Temperatures plunge. And still, that tiny heartbeat goes on.

Lessons for a Warming Planet

Today, as the world faces its sixth mass extinction—this one driven by human activity—scientists are eager to understand what makes some species more resilient than others.

The night lizard’s story offers a vital lesson. It suggests that survival is not always about being the fastest, biggest, or most prolific. Sometimes, it’s about being patient. Being hidden. Being adaptable in quiet, unexpected ways.

By studying survivors of ancient apocalypses, researchers may better predict which modern species are most at risk—and which may have a fighting chance.

A Whisper from the Deep Past

The survival of night lizards is a whisper from deep time, a reminder that life is more tenacious—and more surprising—than we often realize.

They endured when titanic beasts fell. They crept forward, scale by scale, across epochs of fire and ice. And though the dinosaurs are gone, these little lizards remain, tucked into crevices, basking in the sun, carrying the silent legacy of a world long destroyed.

As we look to the future, they look to the past—and remind us that sometimes, the smallest lives leave the longest echoes.

Reference: Chase D. Brownstein et al, Night lizards survived the Cretaceous–Palaeogene mass extinction near the asteroid impact, Biology Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2025.0157