Beneath your feet, even now, the Earth simmers. We walk on a planet born in fire, shaped by titanic forces we cannot see, and driven by energy deep beneath its crust. Among the most dramatic and awe-inspiring of these forces are volcanoes—fountains of molten rock that burst forth from the depths of the planet. They have the power to obliterate cities, choke skies with ash, and, paradoxically, breathe life into barren lands. From the primordial past to the present moment, volcanoes have played a central role in sculpting the Earth’s surface and crafting the environments in which life has flourished. To understand our world, we must understand the mighty volcano.

A Journey to Earth’s Fiery Core

Imagine descending through the layers of Earth: through the brittle crust, into the viscous mantle, and deeper still to the seething, pressurized core. It is down here, in this infernal interior, that volcanoes are born. While the core is a swirling sea of molten iron, the mantle above it consists of semi-solid rock, hot enough to move slowly over geologic time. This movement gives rise to convection currents—like boiling soup—which, in turn, cause the Earth’s plates to shift and interact.

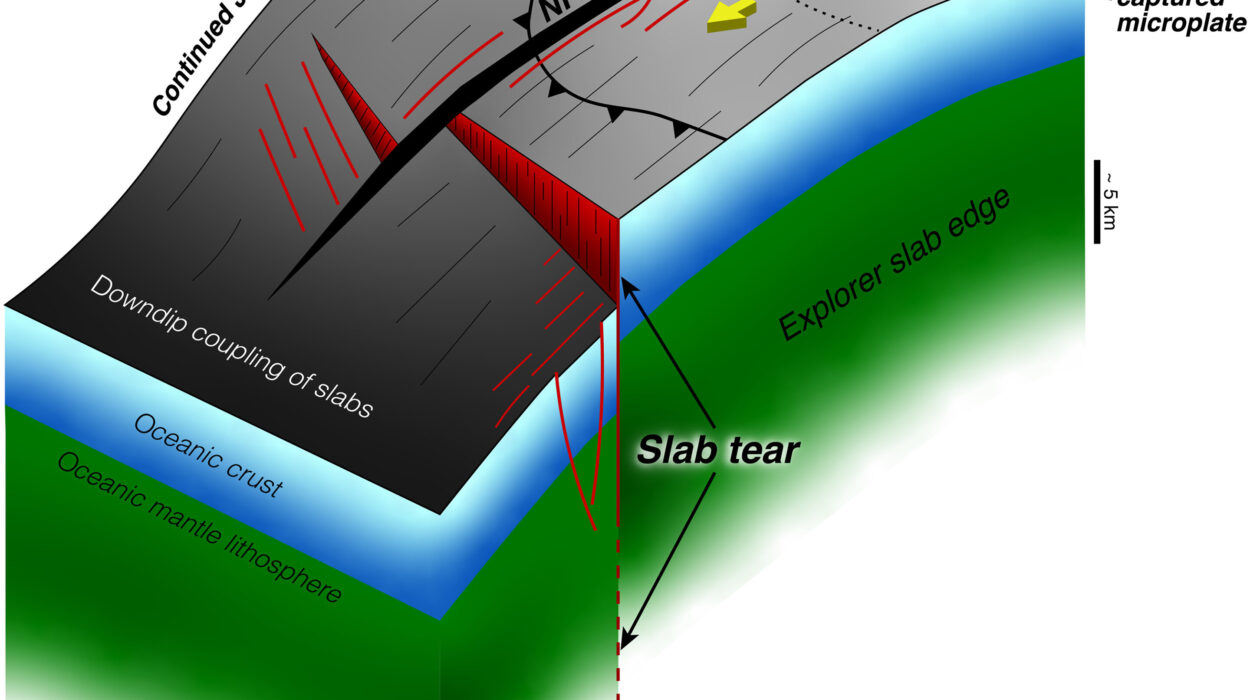

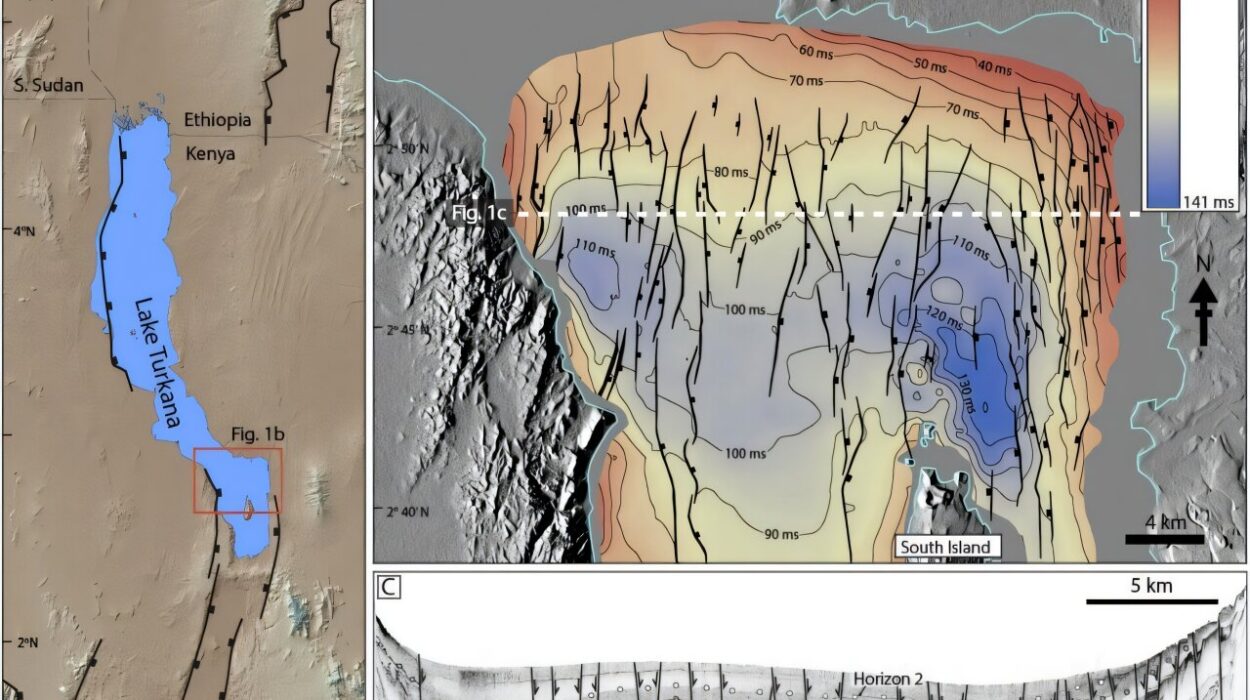

Where these colossal plates meet, split apart, or ride over each other, volcanoes are born. Some rise in subduction zones where an oceanic plate dives beneath a continental one, melting into magma. Others emerge in rift zones where plates pull apart, allowing molten rock to surge upward. Still others bubble up in the middle of plates from hot spots—plumes of magma welling up from deep in the mantle, such as those that birthed the Hawaiian Islands.

Volcanoes are not random accidents of nature; they are written into the architecture of Earth itself. They are the pressure valves of a dynamic planet.

Earth’s Earliest Breath: Volcanoes and the Young Planet

Go back in time, not hundreds or thousands of years, but billions. In Earth’s infancy, the planet was a chaotic hellscape. Meteorites bombarded its surface. The atmosphere, if it could be called that, was a poisonous mix of steam, carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and ammonia. Life had not yet emerged. The surface was a molten wasteland, and volcanoes ruled.

During this era, volcanic activity was far more intense than anything we witness today. These early eruptions released vast quantities of gas and vapor, helping to form Earth’s early atmosphere. The outgassing of volcanoes—releasing water vapor, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen—was crucial. Without volcanoes, Earth might have remained a cold, lifeless rock in space.

Water vapor condensed over time to form the first oceans. Carbon dioxide, which was initially abundant, became trapped in rocks and oceans, eventually allowing oxygen to rise. The very air we breathe today is, in part, a legacy of ancient volcanic eruptions. Volcanoes were midwives to the atmosphere.

Mountains of Fire: Sculptors of Landscapes

Volcanoes do not merely spew fire and fury. They are architects of land. Their eruptions, sometimes violent, sometimes gentle, bring forth new mountains, islands, and valleys. Lava flows cool and harden into rock. Ash settles and builds layers. Over centuries, these materials accumulate, giving birth to towering peaks and island chains.

Consider the Hawaiian Islands—each one a volcanic monument rising from the Pacific. They were built slowly, one eruption at a time, by a single hot spot burning through the moving Pacific Plate. As the plate drifts northwestward, new volcanoes rise while old ones grow dormant and erode into atolls.

In Iceland, volcanoes erupt where the North American and Eurasian plates pull apart, continuously building new land and reshaping the island. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge runs through the country, making it one of the most volcanically active places on Earth.

Volcanoes also create calderas—huge, bowl-shaped depressions formed when a volcano collapses into itself after an eruption. The caldera of Yellowstone, now a supervolcano quietly simmering, is a testament to the cataclysmic power of subterranean pressure.

Even on continents, volcanic mountain ranges like the Andes, Cascades, and Japanese Alps owe their existence to relentless eruptions over millions of years. These volcanoes are not just scars on Earth’s crust—they are monuments to its vitality.

Volcanic Soil and the Bloom of Life

The aftermath of an eruption can look apocalyptic—fields of blackened rock, rivers of cooled lava, forests reduced to ash. But this destruction is not the end of the story. It is the beginning of renewal. Volcanoes, in time, create some of the most fertile lands on the planet.

When volcanic rock breaks down, it releases nutrients such as potassium, phosphorus, and trace elements essential for plant life. Rain and weathering accelerate this process, turning lava flows into rich soil. From the ashes of destruction, green returns.

This is why volcanic regions like Java in Indonesia, the slopes of Mount Etna in Italy, or the farmlands of Rwanda support dense human populations and thriving agriculture. The people who live in these zones often accept the risks of eruption for the rewards of volcanic fertility.

In Hawaii, taro and sweet potatoes flourish in volcanic soil. In Central America, coffee plantations cling to mountainsides formed by long-extinct volcanoes. In Iceland, geothermal energy—also a gift from volcanic activity—powers homes, heats greenhouses, and keeps the island habitable through long winters.

Volcanoes kill. But they also nourish.

Ash in the Sky: Volcanoes and Global Climate

A single eruption can shake the world. Not just the ground, but the sky. When volcanoes eject ash and gases high into the atmosphere, they can cool the entire planet. The particles reflect sunlight, reducing solar energy and temporarily lowering global temperatures.

In 1815, Mount Tambora in Indonesia erupted with such force that it altered the course of history. The eruption ejected so much ash into the stratosphere that global temperatures dropped, leading to what became known as “The Year Without a Summer.” Crops failed across Europe and North America. Famine followed. Even the gloomy skies inspired literature—Mary Shelley wrote “Frankenstein” during that cold, gray summer.

Volcanoes also release sulfur dioxide, which can form sulfate aerosols that linger in the upper atmosphere. These aerosols enhance the cooling effect. In modern times, scientists watch volcanic eruptions closely, not only for their immediate dangers but also for their potential impact on climate.

Interestingly, some climate models even propose using artificially created volcanic effects—called “geoengineering”—to cool the planet in response to global warming. It’s a controversial idea, but it underscores the powerful role volcanoes have played in Earth’s climate system throughout time.

The Ring of Fire and a World on Edge

Look at a map of the Pacific Ocean, and you’ll notice a fiery necklace encircling it. This is the Ring of Fire—a chain of volcanoes and tectonic boundaries stretching from New Zealand through Indonesia, Japan, Alaska, and down the western coasts of the Americas. Nearly 75% of the world’s active and dormant volcanoes lie along this volatile rim.

Why is it so active? Because it is where multiple tectonic plates meet and grind against one another. Subduction zones—where one plate dives beneath another—dominate the Ring of Fire, creating the perfect conditions for explosive volcanoes and deadly earthquakes.

Here, millions of people live in the shadow of volcanoes. Some are monitored constantly, like Japan’s Sakurajima or Washington State’s Mount Rainier. Others, like Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia, have erupted with little warning, taking thousands of lives.

In many of these places, culture and volcano are deeply intertwined. The Ainu people of Japan once worshipped Mount Fuji as a goddess. The people of Indonesia leave offerings to placate Mount Merapi. Even modern nations prepare for eruptions with drills, sensors, and evacuation plans. Living near a volcano means living with both beauty and danger, fertility and risk.

Underwater Fire: Hidden Volcanoes Beneath the Waves

Not all volcanoes stand tall above the land. In fact, most of Earth’s volcanic activity occurs unseen, beneath the oceans. Along the mid-ocean ridges—long chains of underwater mountains—lava continuously seeps out, creating new seafloor and spreading the ocean basins.

These submarine volcanoes shape the ocean floor, give rise to hydrothermal vents, and sustain bizarre ecosystems. Around the vents, superheated, mineral-rich water gushes out, supporting life forms that thrive without sunlight. Here, tube worms, giant clams, and strange bacteria survive on chemosynthesis, not photosynthesis—proof that life can exist in the most extreme places.

These underwater volcanoes also build islands. In time, enough lava accumulates to break the ocean’s surface. This is how the Azores, the Galápagos, and even Iceland came to be.

Earth’s volcanic story is not just one of land and sky—it is also a tale told in the deepest seas.

Volcanoes of the Future: Science, Safety, and Survival

We know more about volcanoes today than ever before. Satellites scan them from orbit. Seismic monitors listen to their rumbles. Gas sensors sniff their emissions. But volcanoes remain notoriously unpredictable. They can slumber for centuries and then awaken in fury.

Scientists now use a variety of tools to forecast eruptions—ground deformation data, gas emissions, seismic activity, even satellite radar. These methods can help provide early warnings and save lives. But forecasting is not a crystal ball. The complexity of volcanic systems means that surprises still happen.

Climate change may influence volcanic risk, too. As glaciers melt and reduce pressure on volcanic systems, eruptions may become more frequent in regions like Iceland and Alaska. Population growth also means more people are living near volcanoes, raising the stakes of every eruption.

Still, the study of volcanoes is not only about danger—it’s about wonder. It’s about understanding the forces that made our continents, built our mountains, and gave birth to the atmosphere. It’s about looking at a plume of smoke rising from the Earth and seeing a message from the planet’s heart.

Conclusion: Fire That Shapes the World

Volcanoes are creators and destroyers. They sculpt continents, give rise to fertile lands, influence global climate, and remind us of Earth’s raw, untamed power. They have shaped the surface of the Earth for billions of years, and they will continue to do so long after we are gone.

In a world that often seems disconnected from its roots, volcanoes are a fierce reminder of our planet’s living, breathing soul. To study them is to peer into Earth’s deep past and glimpse its dynamic future. To live in their shadow is to understand both the peril and the promise of life on a restless planet.

So the next time you see an image of a smoking volcano or hear of an eruption on the news, remember: it is not just a spectacle. It is the Earth shaping itself—again and again—writing its story in fire and stone.