Imagine this: you’re suffering from persistent headaches. You’ve tried different medications, visited doctors, and finally, you’re enrolled in a clinical trial. You’re given a new pill that the researchers believe might help. A few days in, you begin to feel better—your headaches diminish, your energy returns, and you can think clearly again. A miracle drug? Not quite. At the end of the trial, you discover you were taking a sugar pill all along—just a capsule filled with starch or lactose, without a single active pharmaceutical ingredient. And yet, it worked.

This phenomenon, known as the placebo effect, is one of the most fascinating, mysterious, and controversial aspects of medicine and psychology. It’s a testament to the power of the mind over the body, a delicate dance between belief and biology, and a phenomenon that has puzzled scientists and physicians for over a century.

But what exactly is the placebo effect? How can something with no real medicinal value produce genuine, measurable changes in health? Are we simply fooling ourselves, or is there a deeper, neurobiological reality at play? This article dives deep into the world of placebos to explore the magic—and science—behind fake pills that can heal real pain.

Defining the Placebo: More Than Just a Dummy Pill

The word “placebo” comes from Latin, meaning “I shall please.” Historically, it was used in medicine to describe treatments given more to appease patients than to cure them. In modern terms, a placebo is any treatment that has no therapeutic effect on the condition it’s intended to treat—no active ingredients, no biological mechanism of action. Placebos can take many forms: sugar pills, saline injections, sham surgeries, or even fake acupuncture.

But what’s extraordinary is that these inert treatments can often lead to real improvements. In clinical trials, patients who receive placebos frequently report reductions in pain, improvements in mood, better sleep, and relief from various symptoms—even when they know they’re taking a placebo.

This effect challenges our traditional understanding of medicine. It forces us to consider not only what we take but what we believe about what we take. In essence, the placebo effect reveals that healing isn’t just about chemicals and cells—it’s also about context, expectation, and the mind’s profound influence over the body.

A Brief History of the Placebo

The placebo effect isn’t new. It’s been lurking in the background of medicine for centuries, long before it was formally named or studied. In the early days of medicine, treatments like bloodletting, leeching, and herbal tonics were often prescribed more for their symbolic or ritual value than for any actual healing properties. These treatments sometimes worked—not because they had therapeutic value, but because patients believed they did.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, as scientific medicine began to emerge, doctors began to observe that patients sometimes improved even when given treatments they knew were inactive. The term “placebo” began to appear in medical literature, initially as a somewhat dismissive label for useless remedies.

But the scientific study of the placebo effect really took off in the mid-20th century. After World War II, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) became the gold standard for testing new drugs. These trials often included a placebo group, and researchers were surprised to find that a significant percentage of patients in this group improved—even though they had received no actual medication. This unexpected finding sparked a wave of research into the placebo effect, transforming it from a medical footnote into a subject of intense scientific interest.

The Science Behind the Placebo Effect

At first glance, the idea that a fake pill could produce real healing might seem like a psychological trick, nothing more than wishful thinking. But modern science has shown that the placebo effect is far more complex—and far more real—than simple self-deception.

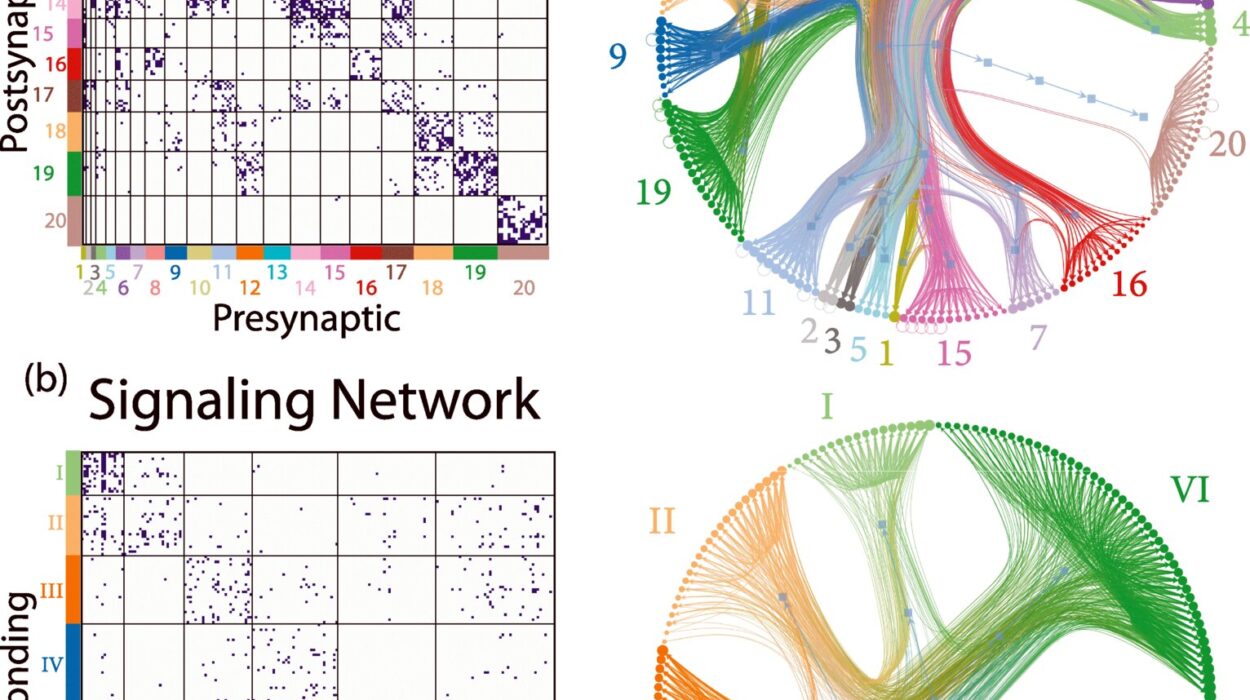

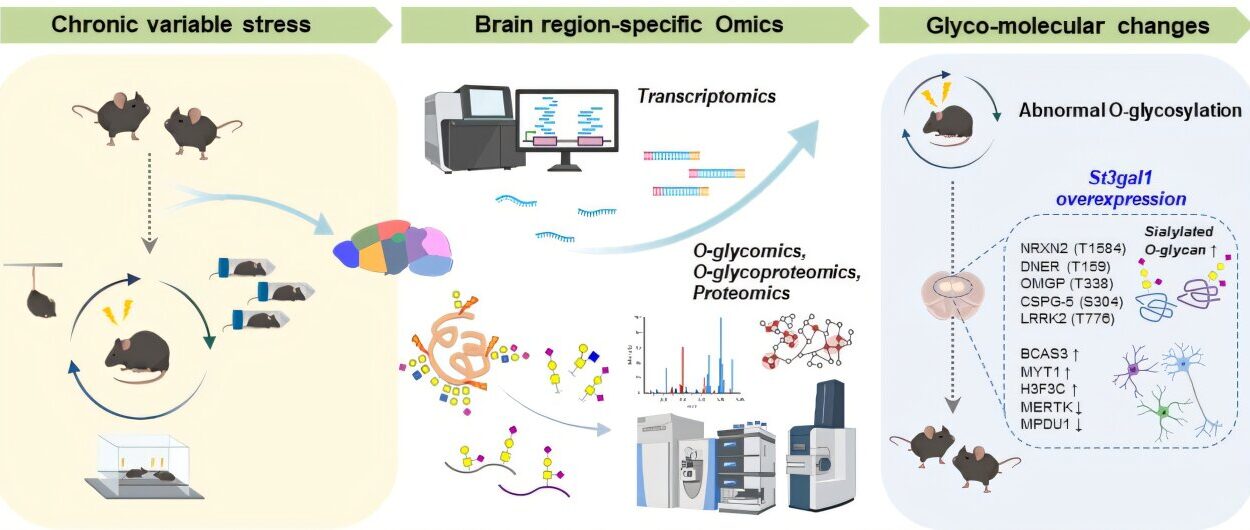

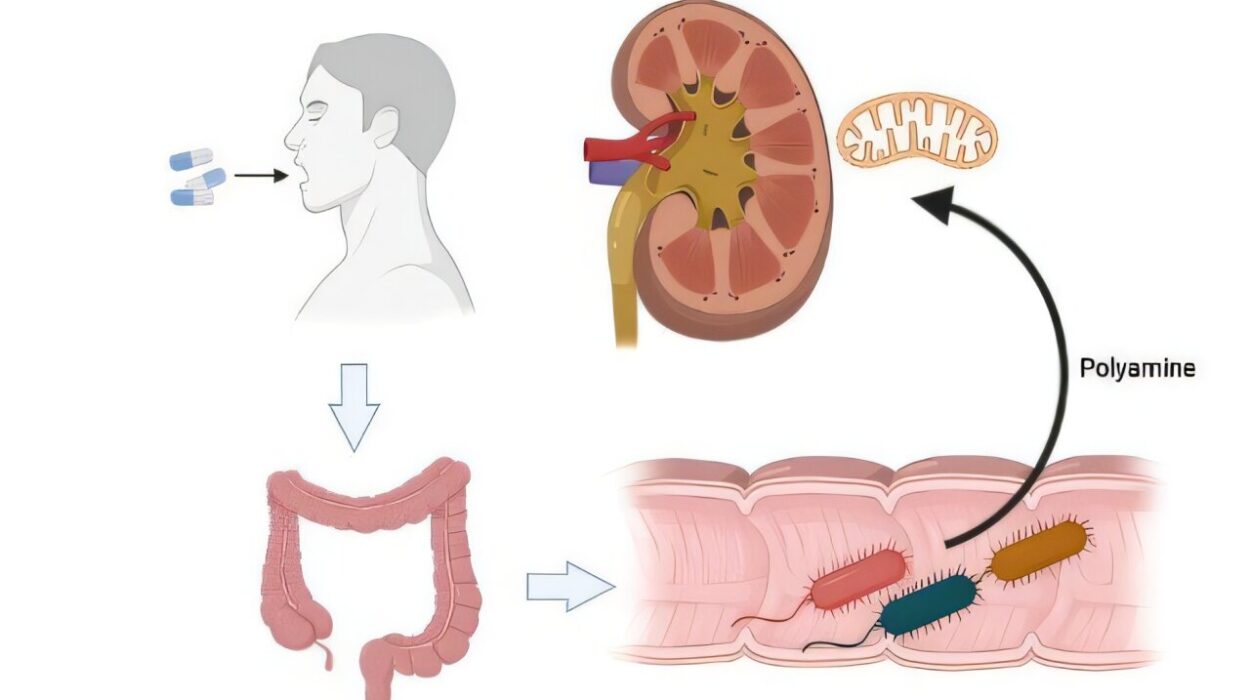

When a person takes a placebo, several things happen simultaneously in the brain and body. Expectations of improvement trigger the brain to release various chemicals, including endorphins (natural painkillers), dopamine (associated with reward and pleasure), and even serotonin (which regulates mood). These chemicals can produce effects similar to those of real drugs, reducing pain, improving mood, and enhancing a sense of well-being.

Functional MRI (fMRI) studies have shown that placebo treatments can activate the same brain regions that are affected by actual medications. For example, in placebo-treated patients with Parkinson’s disease, dopamine production in the brain increases, just as it does with active drugs. In people with depression, placebos can lead to changes in brain activity similar to those seen with antidepressant medications.

This suggests that the placebo effect isn’t just psychological—it’s neurobiological. The brain, through expectation, belief, and context, initiates a cascade of physiological responses that can result in real changes to health.

Conditioning and Expectation: The Mental Mechanisms

Two key psychological processes help explain how the placebo effect works: conditioning and expectation.

Conditioning refers to the learned associations between certain treatments and healing. If you’ve taken a particular medication before and it helped, your brain starts to associate the act of taking that pill with relief. The next time you take something that looks and feels like that medication—even if it’s a placebo—your brain responds as if healing is on the way.

Expectation plays an even more powerful role. When patients believe a treatment will help them, their brains begin to simulate the anticipated improvement. This belief can alter perception, reduce pain, improve symptoms, and even influence immune responses. In some cases, patients have reported side effects from placebos—known as the “nocebo effect”—simply because they expected them.

The doctor-patient relationship also plays a crucial role. The way a treatment is presented, the confidence of the healthcare provider, and the rituals of medicine (white coats, clinical settings, stethoscopes) all contribute to the sense that healing is taking place, which strengthens the placebo response.

Placebos in Pain Management

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for the placebo effect comes from studies of pain. Pain is not just a physical sensation—it’s also shaped by emotions, thoughts, and expectations. This makes it particularly susceptible to the influence of placebos.

Numerous clinical trials have shown that placebo treatments can significantly reduce pain in conditions like migraines, back pain, arthritis, and even post-surgical pain. In some studies, the pain relief experienced from a placebo rivals that of strong analgesics like morphine.

Researchers believe this is due in part to the brain’s release of endogenous opioids, natural chemicals that bind to the same receptors as painkillers. Placebos can trigger this release, leading to genuine analgesia.

Moreover, the way a placebo is administered can affect its potency. Placebo injections tend to be more effective than placebo pills, and even the color, size, and branding of a placebo pill can influence its effectiveness. A large, red capsule labeled as a “strong pain reliever” will likely work better than a small, white, unlabeled tablet—even if both are sugar.

Placebos and Mental Health

Mental health conditions—such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia—are also fertile ground for placebo research. These conditions involve complex interactions between the brain, emotions, and behavior, making them highly responsive to belief and expectation.

Antidepressant trials, for instance, often show high placebo response rates. In some studies, up to 50% of patients taking a placebo report significant improvement. This has led to intense debate in psychiatry about the efficacy of certain drugs and the role of belief in mental health treatment.

Some researchers argue that the placebo effect should be embraced more openly in mental health care. If a sugar pill can help alleviate depression by altering brain chemistry through expectation, then perhaps the therapeutic environment, patient-clinician relationship, and positive reinforcement are just as important as medication.

The Ethical Quandary: Is It Right to Use Placebos?

Despite its remarkable power, the placebo effect presents a thorny ethical dilemma. Is it acceptable for doctors to prescribe treatments that have no active ingredients? Does doing so involve deception, and if so, is it justifiable if it helps the patient?

Traditionally, the use of placebos was considered deceptive and unethical in clinical practice. Doctors were expected to be honest, and giving a placebo implied lying. However, newer studies have shown that placebos can still work even when patients are told they’re taking one. These are called “open-label placebos.”

In these studies, patients are explicitly informed that they’re taking a substance with no active medication, yet they still report improvements. This suggests that the ritual of treatment itself—the act of caring, the context, the hope—can trigger healing, even when there’s no deception involved.

This has opened up a new area of ethical inquiry. Some researchers argue that harnessing the placebo effect, honestly and transparently, could be a valuable part of modern medicine, especially in areas where effective treatments are limited or carry significant side effects.

Placebos in Clinical Trials: Separating Signal from Noise

The placebo effect isn’t just a curious footnote in medicine—it’s a central component of how we evaluate drugs. Every new medication must prove its effectiveness in comparison to a placebo. This means that if a new drug can’t perform better than a sugar pill, it often doesn’t make it to market.

This has raised a paradox in pharmaceutical research: how do you develop drugs that are significantly better than a treatment that already produces meaningful results simply through belief?

The strength of the placebo effect has actually made it harder to test certain medications. In conditions like depression, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic pain, the placebo response is so strong that proving the added benefit of a real drug becomes statistically challenging.

Some companies have even redesigned their trials to include “active placebos”—placebos that mimic the side effects of real drugs to keep patients from guessing whether they’re in the treatment or placebo group. The goal is to ensure that belief and expectation are as evenly distributed as possible across trial arms, allowing for a cleaner comparison.

Placebos Beyond Pills: Surgery, Devices, and Ritual

The placebo effect isn’t limited to pills. In fact, it extends far beyond them—into surgeries, medical devices, and holistic practices.

Sham surgeries have been used in clinical trials to study conditions like knee osteoarthritis and Parkinson’s disease. In these trials, patients undergo the rituals of surgery—anesthesia, incisions, recovery—but no actual therapeutic procedure is performed. Astonishingly, many of these patients experience significant improvements, suggesting that the expectation of surgery can itself be healing.

Similarly, fake acupuncture (where needles are placed randomly or don’t penetrate the skin) can produce benefits comparable to real acupuncture in some studies. The ritual of the treatment—the therapist’s attention, the setting, the process—appears to be a crucial part of its effectiveness.

This insight has led to a reevaluation of alternative medicine. While many such treatments lack scientific evidence of efficacy beyond placebo, the context and experience they offer may still provide real relief. Critics argue that this is not enough to justify their use, while proponents believe that if something helps—even through placebo—it has value.

Harnessing the Power of the Placebo Effect

Rather than dismiss the placebo effect as a nuisance or a trick, many modern clinicians are now looking at how to harness its power ethically and effectively. This involves rethinking the way medicine is practiced—not just focusing on drugs and diagnoses, but also on empathy, communication, and the therapeutic alliance.

Studies show that when doctors express optimism about a treatment, patients are more likely to benefit. When they take time to listen, explain, and connect, the placebo effect is amplified. This suggests that medicine is not just a technical practice but a deeply human one, rooted in trust, meaning, and shared hope.

Some experts advocate for “placebo-enhanced” medicine—a model where the best of biomedical science is combined with strategies that enhance the placebo response. This might include mindfulness, narrative medicine, patient education, and other approaches that engage the mind as well as the body.

Conclusion: The Mind-Body Mystery

The placebo effect stands as one of the most intriguing phenomena in science and medicine. It blurs the boundaries between mind and body, illusion and reality, hope and healing. It forces us to acknowledge that the brain has profound power over the body, and that belief, trust, and care are not just extras—they are essential components of health.

Far from being a quirk or a nuisance, the placebo effect may offer one of the most profound lessons in modern medicine: that healing is not just about chemistry, but also about context, connection, and the mysterious interplay between perception and physiology.

In a world increasingly driven by data and precision, the placebo effect reminds us that sometimes, the simplest things—a kind word, a hopeful gesture, a sugar pill—can trigger the most profound transformations. It challenges us to embrace a more holistic view of healing, where science and story, biology and belief, come together in the service of human well-being.