Far below the reach of sunlight, where the ocean presses down with crushing weight, the seafloor quietly records the planet’s most violent moments. Every so often, the ground shudders, slopes collapse, and huge underwater landslides roar downslope like avalanches in the dark. When the chaos settles, thin layers of mud and sand spread across the deep ocean floor. These layers are called marine turbidites, and for decades scientists have treated them like pages in a hidden history book of earthquakes.

But there has always been a problem with this book. Its pages can be misleading.

A storm can churn the ocean. A flood can send sediment racing offshore. Both can leave behind mud layers that look suspiciously like earthquake debris. Without a clear way to tell the difference, scientists have had to live with uncertainty. Were these layers really written by earthquakes, or were they forged by weather?

Now, a new study published in Science Advances offers a way to read the seafloor’s story with far greater confidence. By connecting turbidites directly to the underwater landslides that created them, researchers have found a way to turn a blurry record into a sharply focused timeline of massive earthquakes.

A Blurry Map of a Violent Past

Marine turbidites have long been attractive to scientists trying to reconstruct earthquake histories. On land, erosion and human activity erase traces of ancient quakes. Deep underwater, those traces remain quietly preserved. Each thick pulse of mud can mark a moment when the Earth’s crust suddenly gave way.

Yet the deep ocean is notoriously hard to study. It lies far beyond easy reach, and for years scientists relied on coarse, low-resolution maps that smoothed over crucial details. Without seeing the exact shape of underwater hills, slopes, and scars, it was nearly impossible to link a mud layer on the seafloor to a specific landslide uphill.

That gap left room for doubt. If scientists could not prove where a turbidite came from, they could not prove what caused it. Earthquakes and storms blurred together in the geological record.

This uncertainty mattered deeply. Earthquake timelines guide hazard planning, risk models, and public understanding of seismic danger. A shaky record leads to shaky conclusions.

Diving Deeper Than Ever Before

To sharpen that record, U.S. Geological Survey research geologist Jenna Hill and her colleagues decided to look closer than anyone had before. Off the coast of Crescent City, California, they sent autonomous underwater drones and tethered robots into the depths, where pressure is immense and darkness absolute.

These machines did something revolutionary. They mapped the seafloor in high definition, revealing steep hills, scarred slopes, and sediment pathways in striking detail. What once looked like vague smudges on a map suddenly became crisp landscapes shaped by motion and collapse.

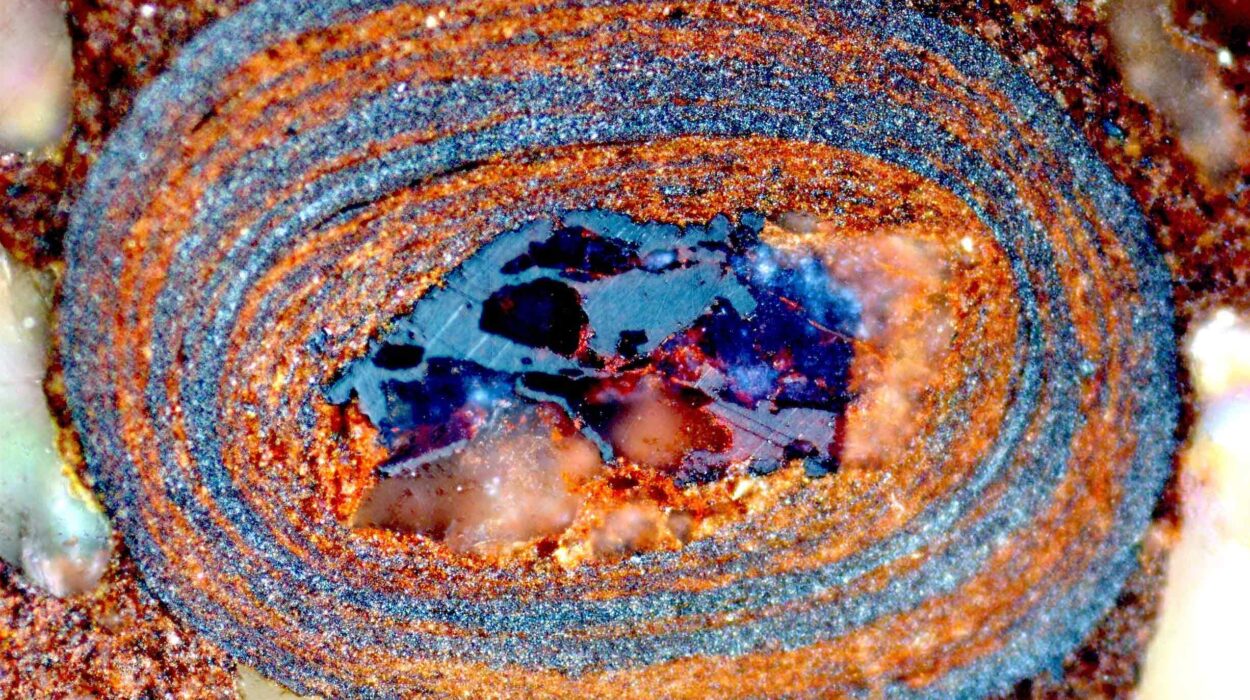

But mapping alone was not enough. To understand timing, the team needed samples. They drilled long tube cores of mud from two places: the turbidite layers spread across the deep ocean floor, and the steep underwater hills where landslides were likely to begin.

These samples carried time within them. Using radiocarbon dating, the researchers could determine how old the mud was, layer by layer. The expectation was straightforward. In most environments, sediment settles from the top down. Older mud lies below, newer mud above. A landslide should scrape off surface layers, exposing older material underneath.

What they found instead was startling.

Mud That Defies Gravity and Time

The mud from the hills and the mud from the seafloor turned out to be the same age.

This result ran counter to basic expectations. If the hills were simply eroding from the top, the material beneath a landslide scar should have been much older than the freshly deposited turbidite below. But the ages matched. Again and again.

The only explanation was that something unusual was happening beneath the seafloor. The hills were not just losing sediment. They were being refilled.

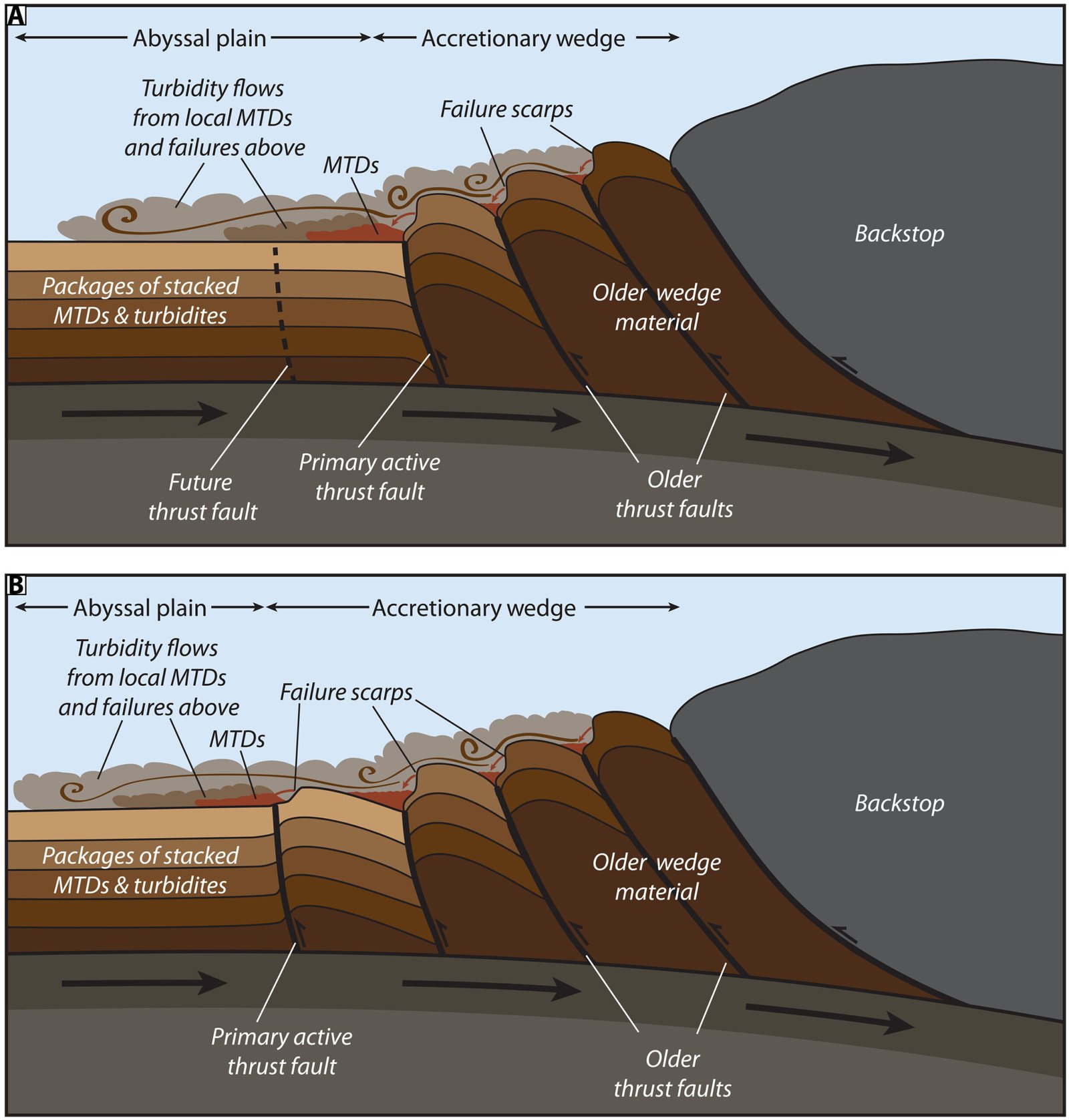

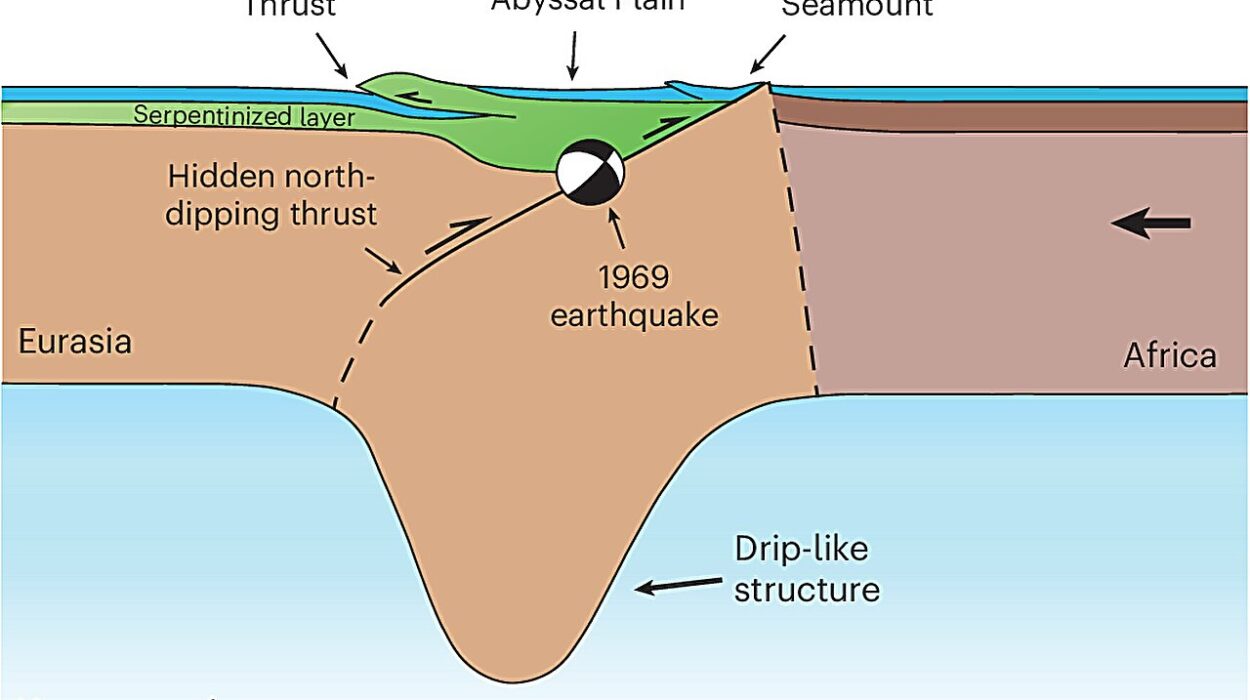

The study area sits on a subduction zone, a place where one tectonic plate slides beneath another. As these plates grind together, immense forces squeeze the Earth’s crust. That pressure pushes fresh mud upward from below the seafloor, lifting it into the tops of steep underwater hills.

Instead of aging quietly, these hills are constantly renewed from underneath. When an earthquake strikes, the newly uplifted mud collapses, racing downslope and spreading across the deep ocean floor as a turbidite. The mud on the hill and the mud below are born at nearly the same moment.

This hidden process turns coincidence into connection. The matching ages are no longer confusing. They are a signature.

When Weather No Longer Fits the Story

This discovery solves one of the biggest problems in turbidite research. The hills that feed these underwater landslides sit in the deep ocean, far removed from the reach of surface storms and floods. Wind, waves, and rain simply cannot disturb them.

That fact changes everything.

If mud from these hills slides downslope, weather is no longer a plausible culprit. The only force powerful enough to trigger such collapses is ground shaking. In other words, earthquakes.

By linking turbidites directly to landslides sourced from deep, storm-proof hills, the researchers gained something rare in geology: confidence. Each layer of mud is no longer just a possible earthquake signal. It is a reliable one.

The seafloor, once an unreliable witness, becomes a trustworthy narrator.

A New Way to Read the Ocean’s Memory

The researchers describe their approach as more than a local success. In their own words, “Our results present a paradigm for marine turbidite paleoseismology and have important implications for site selection and seismoturbidite interpretations along subduction zones globally.”

This is a shift in how scientists choose where to look and how they interpret what they find. By focusing on deep-ocean settings shaped by subduction and refilled from below, researchers can build earthquake histories that are less ambiguous and more precise.

Using this method, the team reconstructed a detailed timeline of massive earthquakes stretching across a 600-mile coastline, from Northern California up to Canada. The record revealed a sobering rhythm. These giant earthquakes occur, on average, every 500 years.

The last one struck in the year 1700.

For the first time, this timeline rests on a foundation that directly ties cause to effect, quake to landslide, landslide to mud layer. The ocean floor is no longer just recording chaos. It is explaining it.

Why This Discovery Matters Now

Understanding earthquake history is not an academic exercise. It shapes how societies prepare for the future. When scientists know how often massive earthquakes strike, they can better estimate risk and urgency.

This new approach sharpens that understanding. It replaces guesswork with evidence rooted in the mechanics of the Earth itself. By proving that certain turbidites can only be caused by earthquakes, the study removes a major source of uncertainty from seismic timelines.

The implications extend beyond one coastline. Subduction zones exist around the world, and the same hidden process of mud being squeezed upward may be quietly shaping earthquake records elsewhere. What was once thought unreadable or unreliable may suddenly become clear.

At the heart of this research is a simple but powerful idea. The deep ocean remembers. With the right tools and the right questions, scientists can finally listen.

Study Details

Jenna C. Hill et al, Widespread abyssal turbidites record megathrust earthquake-triggered landslides and coseismic deformation in the Cascadia subduction zone, Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx6028