Far out over the tropical Pacific, the sea stretches endlessly toward the horizon, shimmering under the relentless heat of the Sun. The air is heavy with moisture, and the sea’s surface is warm — warmer than the human body — a silent storehouse of energy waiting to be unleashed. Here, where ocean and atmosphere meet in a delicate dance, something begins to stir. A cluster of thunderstorms, fueled by the rising columns of hot, wet air, starts to spiral, drawn into a pattern both beautiful and ominous. The winds begin to circle, slowly at first, then faster, as though the sky itself has found a rhythm. This is the seed of a typhoon.

A typhoon is not born in a moment. It grows from subtle beginnings — a ripple in the atmosphere, a disturbance in the trade winds — and gathers its strength from the sea. Over days, that ripple may become an organized system, with thunderstorms feeding on the warm ocean water. The Earth’s rotation bends the moving air into a spiral, a phenomenon known as the Coriolis effect. What was once a scattered set of clouds becomes a unified engine of wind, rain, and fury.

When the winds near the center reach sustained speeds of 118 kilometers per hour (about 74 miles per hour), meteorologists declare it a typhoon. At that point, the storm has achieved a self-sustaining structure, with a central eye, spiraling rain bands, and towering walls of cloud. But a typhoon is more than wind speed on a chart; it is a living system, drawing breath from the ocean and exhaling destruction across the land.

The Science Behind the Spiral

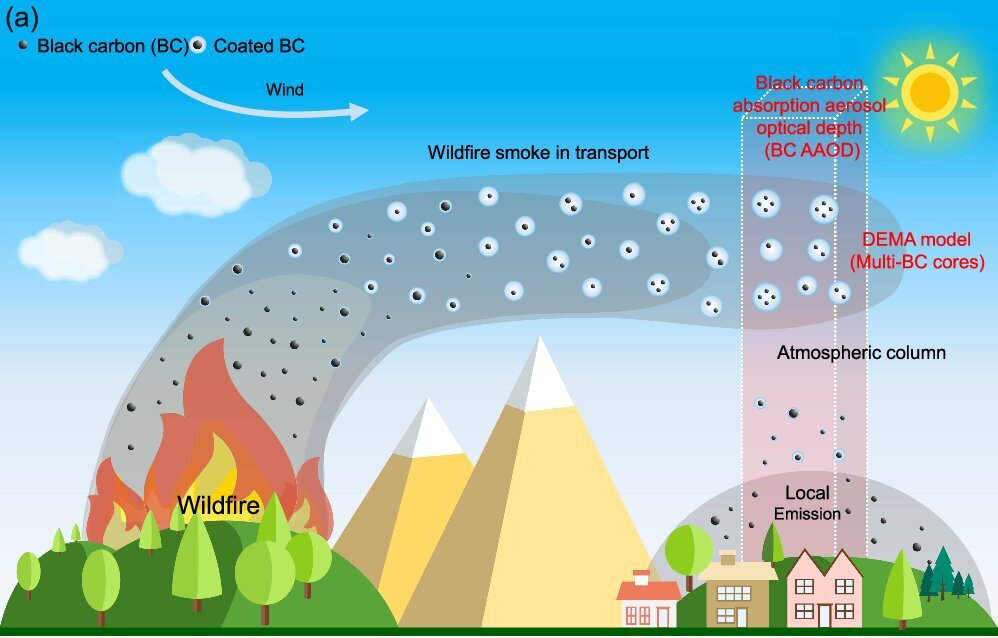

To truly understand what a typhoon is, one must understand the physics that drive it. At its core, a typhoon is a heat engine — a machine that converts the thermal energy of the warm ocean into the kinetic energy of fierce winds. Warm water evaporates into the air above, carrying vast amounts of latent heat. When this moist air rises and cools, the water vapor condenses into clouds and rain, releasing the stored heat into the surrounding atmosphere. This release of energy warms the air, making it lighter and encouraging it to rise even faster.

The rising air creates a zone of low pressure at the surface. Surrounding air rushes in to fill the void, but because the Earth rotates, the incoming winds curve. In the Northern Hemisphere, they spiral counterclockwise; in the Southern Hemisphere, clockwise. As the system intensifies, the spiral tightens and the winds strengthen, creating the classic cyclone structure.

At the heart of the storm lies the eye — a region of relative calm where the skies may clear and the sun may even shine. This is not a place of safety, for surrounding it is the eyewall: a fortress of violent winds and torrential rain, where the storm’s energy is most concentrated. The contrast between the tranquil eye and the roaring eyewall is one of nature’s most dramatic juxtapositions.

Typhoon, Hurricane, or Cyclone?

The word typhoon is a regional name for what scientists call a tropical cyclone. The differences in naming are purely geographic. In the Northwest Pacific Ocean, particularly in the waters near East and Southeast Asia, these storms are called typhoons. In the North Atlantic and the Northeast Pacific, they are called hurricanes. In the South Pacific and Indian Ocean, they are simply cyclones.

Despite the different names, the physical process is the same. All tropical cyclones require warm water — at least 26.5°C (about 80°F) — and favorable atmospheric conditions, including low vertical wind shear, so that the storm’s structure is not torn apart. These requirements mean that typhoons are seasonal, forming most often in late summer and early autumn, when ocean temperatures peak.

The Northwest Pacific is the most active tropical cyclone basin in the world. It produces more storms, and often more intense ones, than any other region. This is why countries like the Philippines, Japan, Taiwan, and China are so frequently in the path of typhoons.

The Power Within

It is difficult to comprehend the sheer energy of a typhoon. A mature storm can be hundreds of kilometers across, with cloud tops reaching more than 15 kilometers into the sky. The winds can exceed 250 kilometers per hour, strong enough to tear roofs from houses, uproot trees, and turn debris into deadly projectiles.

But wind is only part of the danger. Typhoons carry immense amounts of rain, often dumping hundreds of millimeters in a single day. This can cause catastrophic flooding and landslides, particularly in mountainous or densely populated areas. Even more deadly can be the storm surge — a dome of seawater pushed ashore by the storm’s winds. In low-lying coastal regions, storm surges can inundate entire communities, sweeping away buildings and leaving saltwater contamination in their wake.

The total energy released by a large typhoon is almost beyond human imagination. The heat energy given off through cloud formation alone can be equivalent to several hundred times the energy of all the world’s electrical power plants operating simultaneously. This is why, once a typhoon reaches full strength, it can sustain itself for days or even weeks, traveling across vast stretches of ocean.

The Human Cost

Typhoons are not just meteorological events; they are human tragedies and human stories. For those who live in typhoon-prone regions, the arrival of a storm can mean the difference between life as usual and life forever changed.

In the fishing villages of the Philippines, a typhoon’s approach sends boats racing back to port, their crews working urgently to secure them against the coming waves. In the cities of southern China, shopkeepers board up their windows, and residents stock up on food, water, and candles. In Japan, trains are canceled, schools close, and disaster preparedness drills are activated. The tension before landfall is a quiet, collective breath — the waiting for a force that cannot be stopped.

When the storm comes, it is not a single sound but many: the howling of wind through narrow streets, the rhythmic thud of rain on rooftops, the groan of trees bending under strain, the crash of waves breaking over seawalls. Power lines snap, plunging neighborhoods into darkness. Roads vanish under water. People shelter in crowded evacuation centers, huddled together with strangers, sharing news from battery-powered radios.

And then, when the storm passes, the silence returns — but it is a heavy, broken silence. Streets are littered with debris. Houses lie in ruin. The survivors begin the slow, painful work of rebuilding, often with little more than the help of neighbors and the resilience of the human spirit.

Typhoons in History

Throughout history, typhoons have shaped the destinies of nations. In 1274 and again in 1281, Mongol fleets attempting to invade Japan were destroyed by powerful storms, events the Japanese came to call kamikaze, or “divine wind.” These typhoons not only changed the course of Japanese history but also entered cultural memory as acts of divine intervention.

In modern times, typhoons have left their mark in less mythic but equally devastating ways. Typhoon Vera, which struck Japan in 1959, killed more than 5,000 people and remains the deadliest storm in the country’s recorded history. Typhoon Haiyan, which devastated the Philippines in 2013, produced winds among the strongest ever recorded at landfall and left more than 6,000 dead, with millions displaced.

Such storms remind us that, despite advances in forecasting and preparedness, the power of nature can still overwhelm human defenses.

Forecasting and Preparation

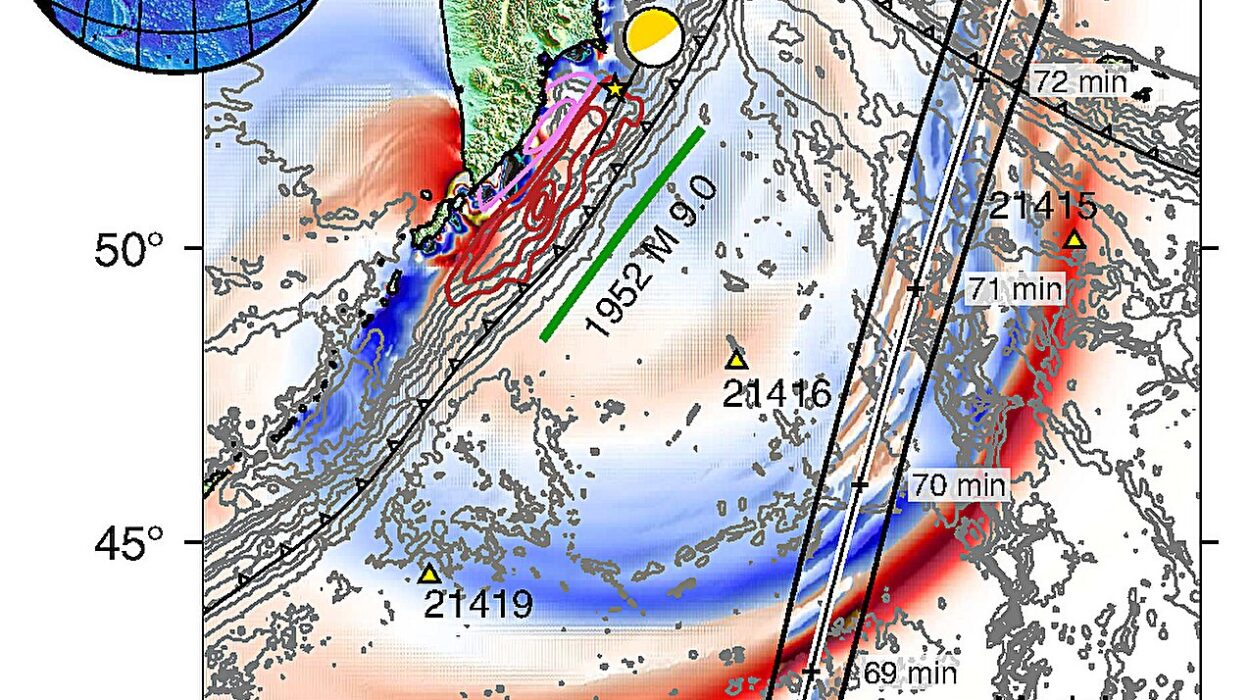

The ability to predict typhoons has improved dramatically over the past century. Meteorologists now use satellites to monitor cloud patterns, ocean temperatures, and wind speeds. Computer models simulate a storm’s possible paths and intensities, allowing governments to issue timely warnings.

Still, forecasting is as much art as science. Small changes in atmospheric conditions can alter a typhoon’s path or strength. A storm predicted to skirt the coast can veer inland; a weakening system can suddenly intensify over a patch of unusually warm water.

Preparation is therefore critical. Coastal communities build seawalls, enforce building codes, and conduct evacuation drills. International cooperation allows data sharing between meteorological agencies. Human adaptation — from improved shelters to better emergency response — has saved countless lives, even as storms themselves grow stronger.

Climate Change and the Future of Typhoons

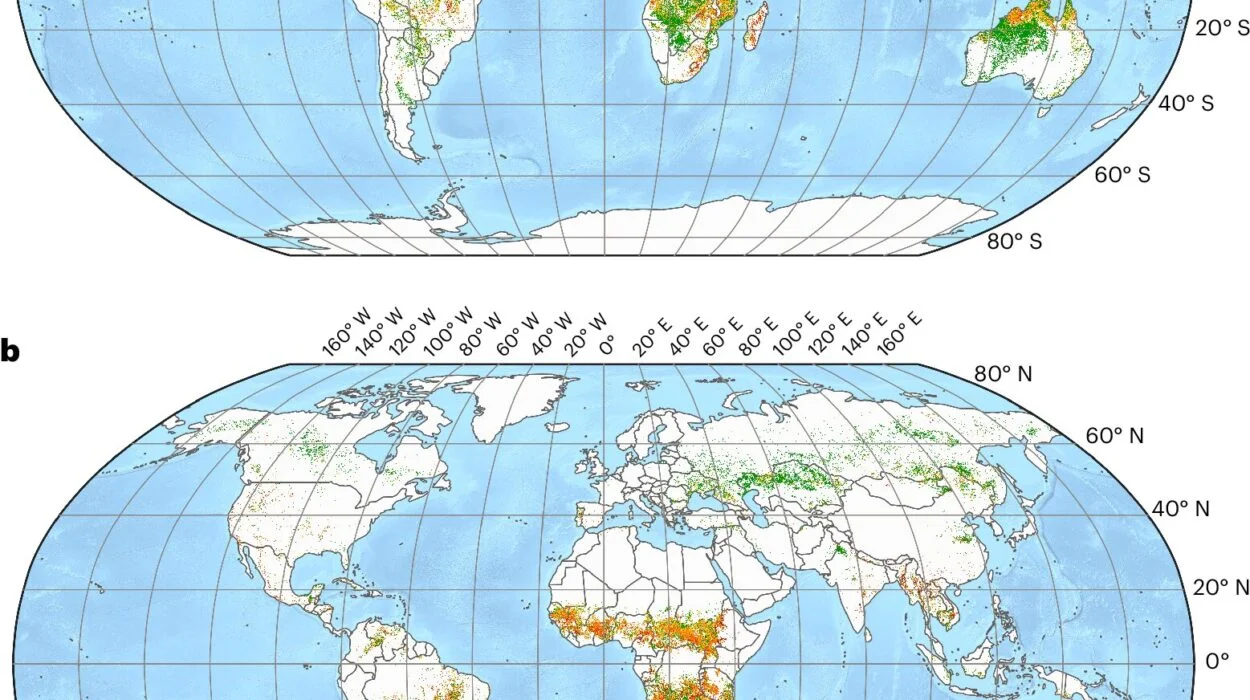

Scientists are increasingly concerned about how climate change may affect typhoons. While the total number of storms each year may not rise dramatically, there is evidence that the most intense storms are becoming more common. Warmer oceans provide more energy, and rising sea levels mean that storm surges can reach farther inland.

In some parts of the world, typhoon seasons are lengthening, and storms are reaching peak intensity closer to shore, leaving less time for preparation. This trend poses serious challenges for communities that already face frequent typhoon impacts.

The future of typhoons will be written not only by nature but by human choices. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, protecting coastal ecosystems like mangroves and coral reefs, and investing in resilient infrastructure will all shape how societies weather the storms to come.

The Awe and the Warning

To witness a typhoon from afar — from a satellite image or an airplane window — is to see one of nature’s most magnificent patterns: a perfect spiral of clouds, serene in appearance, hiding chaos within. From the ground, it is a different experience entirely — one of vulnerability, fear, and respect for forces far beyond human control.

Typhoons remind us that we live on a restless planet, one whose beauty and danger are often intertwined. They are both a natural wonder and a natural hazard, a product of the same physical laws that bring us gentle rain and nourishing sunlight.

For those who survive them, typhoons are not just storms in the sky but milestones in life, moments after which everything is measured in “before” and “after.” They teach us the value of preparation, the importance of community, and the truth that in the face of nature’s greatest powers, humanity’s greatest strength is solidarity.