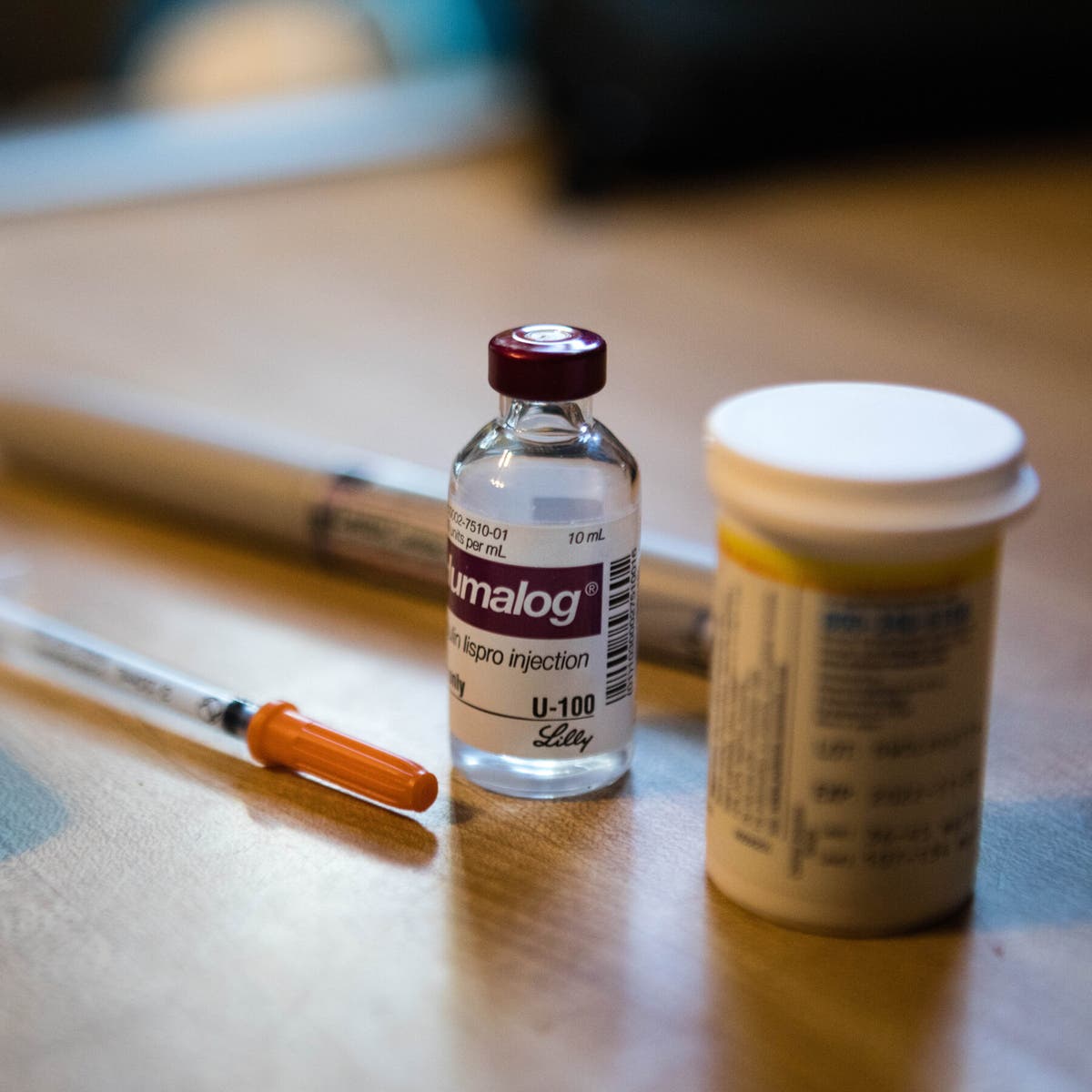

For over a century, people diagnosed with type 1 diabetes have been told the same thing: your body has lost the ability to make insulin, and it won’t come back. The best we can do is help you manage it. Daily injections. Constant glucose monitoring. An invisible tightrope walk between life and death, where one misstep—a skipped meal, a mistimed dose, an unnoticed drop in blood sugar—can send someone into crisis.

But what if that narrative could change?

In a groundbreaking clinical trial, researchers led by a team at the University of Toronto have taken a decisive step toward doing just that. For a small group of adults living with the most severe form of type 1 diabetes, a new stem cell–derived islet therapy called zimislecel has done something once thought impossible: restored their ability to produce insulin naturally—and ended dangerous hypoglycemic episodes.

The findings, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, are more than promising. They may signal a turning point in how we treat—and perhaps eventually cure—type 1 diabetes.

Why Type 1 Diabetes Is So Devastating

More than 8 million people worldwide live with type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune condition in which the body mistakenly attacks and destroys the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Without insulin, the body can’t regulate blood glucose, and without careful management, blood sugar levels can swing wildly—leading to fatigue, organ damage, coma, or even death.

Technological advances such as continuous glucose monitors and automated insulin delivery systems have dramatically improved care in recent years. But they are not perfect. For many patients, especially those with impaired hypoglycemia awareness, these tools still fall short. These individuals lose the ability to sense when their blood sugar is dangerously low, and without quick intervention, the consequences can be fatal.

Doctors have long hoped to replace the lost beta cells using donor transplants. But such treatments rely on scarce human organs, require lifelong immunosuppression, and often fail to restore full insulin independence. A consistent, scalable solution has remained elusive—until now.

The Trial That Reawakened the Pancreas

The zimislecel study, formally titled “Stem Cell–Derived, Fully Differentiated Islets for Type 1 Diabetes,” enrolled 14 adult volunteers across North America and Europe. All had lived with type 1 diabetes for years. All had experienced at least two severe hypoglycemic events in the prior year. And all had used glucose monitoring technology for at least three months before the trial.

Rather than multiple complex surgeries or numerous donor transplants, each participant received just one infusion: a gravity-assisted dose of zimislecel—a therapy made from fully differentiated islet cells derived from allogeneic stem cells. In plain terms, these are lab-grown versions of the same kind of cells their bodies once destroyed.

The treatment was delivered into the portal vein, a major vessel in the liver where islet cells can thrive and function. Participants were placed on glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimens, minimizing the side effects commonly associated with traditional transplant protocols.

From Insulin Dependence to Freedom

The results were nothing short of stunning. Among the 12 participants who received the full dose of zimislecel, every single one was free from severe hypoglycemia a year after the infusion. Their average blood sugar levels (measured by HbA1c) dropped below 7%, the benchmark for healthy glycemic control. They spent more than 70% of their time in the target range of 70–180 mg/dL.

Even more remarkably, 10 of the 12 participants became insulin-independent. The remaining two dramatically reduced their insulin needs. For these individuals, this wasn’t just symptom relief—it was a restoration of internal biological control.

“These results are encouraging in ways we’ve only dreamed of,” said the study’s lead investigator. “To see people living with brittle diabetes experience such a transformation—it’s a glimpse into what the future of treatment might hold.”

Challenges and Cautions Along the Way

Of course, this isn’t a miracle cure—not yet. Like all early-phase clinical trials, the zimislecel study was small, open-label (meaning both patients and researchers knew what was being administered), and lacked a control group. Its results are best described as a powerful first signal, not a final answer.

And there were risks. The most common serious adverse event was neutropenia, a temporary drop in white blood cells, experienced by three participants. Two deaths occurred during the trial: one from cryptococcal meningitis, after the participant received off-protocol glucocorticoids, and one from progression of pre-existing neurocognitive impairment.

Despite these setbacks, the overall safety profile was encouraging. The zimislecel therapy did not trigger unexpected immune reactions or organ damage. And crucially, it demonstrated that a single, donor-independent infusion of lab-grown islet cells could restore insulin production for at least a year.

Why This Therapy Is Different

What sets zimislecel apart isn’t just the outcome—it’s the method. Traditional islet or pancreas transplants rely on human donor organs, which are in extremely short supply and often require multiple transplants to be effective. Zimislecel, by contrast, is manufactured using stem cells grown in labs. That means it can be produced at scale, offering hope for millions of patients, not just a lucky few.

Moreover, the zimislecel cells are fully differentiated before infusion, meaning they arrive ready to perform the tasks of natural beta cells. Earlier attempts at stem cell-based therapies often struggled with immature or unstable cells. Zimislecel seems to avoid that problem, integrating smoothly into the recipient’s physiology.

A Glimpse into a Future Without Injections

Imagine waking up and not having to check your blood sugar. Eating a meal without calculating your carb intake. Traveling without carrying emergency insulin. For many people with type 1 diabetes, these are unimaginable luxuries. But with therapies like zimislecel on the horizon, they may soon become reality.

“The idea that we could grow replacement islets in the lab, infuse them with a simple procedure, and restore natural insulin production—it’s been the holy grail of diabetes research for decades,” said one endocrinologist not involved in the study. “This trial brings us a step closer.”

A larger, more rigorous trial of zimislecel is already underway. Researchers hope to confirm its long-term effectiveness, monitor for late-onset complications, and refine the dosing and delivery process. They are also exploring ways to further reduce the need for immunosuppression—perhaps even eliminating it altogether.

Hope, at Last, for a Cure

For the volunteers in the trial, the impact has been life-changing. Not just in lab numbers or glucose charts, but in the quiet freedom of living without fear. No more waking up in the middle of the night with heart-pounding hypoglycemia. No more needles every few hours. No more wondering if today’s insulin dose will be enough—or too much.

This is not just a medical milestone. It’s a deeply human one.

“We still have a long way to go,” said the study team. “But we now know that it’s possible—truly possible—to give people with type 1 diabetes back something they thought was lost forever: their own insulin.”

For the millions waiting, watching, and hoping, zimislecel may be more than a therapy. It may be the beginning of the end of type 1 diabetes as we know it.

Reference: Trevor W. Reichman et al, Stem Cell–Derived, Fully Differentiated Islets for Type 1 Diabetes, New England Journal of Medicine (2025). DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2506549