For decades, the internet has been described as humanity’s great equalizer, a force capable of dissolving borders, amplifying voices, and unlocking opportunity. Yet beneath that promise lies a persistent fracture. Billions of people still live on the wrong side of the digital divide, cut off by geography, poverty, politics, or infrastructure. In villages beyond fiber routes, on ships crossing open oceans, in deserts, mountains, and disaster zones, connectivity has been unreliable or nonexistent. Then came a bold idea that sounded almost audacious: what if the internet came not from cables in the ground, but from thousands of satellites moving silently across the sky?

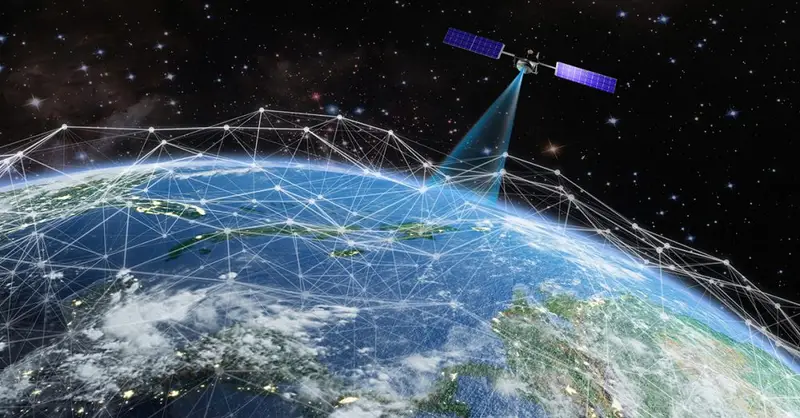

Starlink, a satellite internet constellation built using low Earth orbit satellites, has become the most visible symbol of this vision. It promises broadband-speed internet delivered from space to nearly anywhere on Earth. The idea feels almost poetic: the same stars that guided ancient travelers now carrying data packets, emails, and video calls. But the promise raises a deeper question. Is satellite internet truly the long-awaited solution to the digital divide, or is it only a partial answer wrapped in orbital ambition?

To understand what Starlink represents, and what lies beyond it, we must explore not only the technology itself, but the human stakes, the physics that make it possible, and the social realities that may limit its reach.

The Digital Divide as a Human Story

The digital divide is often described in statistics: percentages of households connected, megabits per second, coverage maps shaded in red and green. Yet behind those numbers are human lives shaped by access or its absence. A student without reliable internet cannot attend virtual classes or access online libraries. A farmer without connectivity cannot check market prices or weather forecasts. A doctor in a rural clinic cannot consult specialists or access digital records. Connectivity is no longer a luxury; it is a gateway to education, healthcare, commerce, and civic participation.

Historically, internet infrastructure followed money and population density. Fiber-optic cables, the backbone of high-speed internet, are expensive to install and maintain. Private companies prioritize cities where costs can be recouped quickly. Even in wealthy nations, rural regions often lag far behind urban centers. In developing countries, vast areas remain unconnected, not because people do not want internet access, but because traditional infrastructure models make it economically unattractive.

Satellite internet has long been proposed as a solution to this problem, but until recently, it came with serious limitations. High latency, slow speeds, and high costs kept it from being a true alternative to terrestrial broadband. Starlink changed the conversation by reimagining satellite internet from the ground up.

How Starlink Works: The Physics of Internet from Space

At the core of Starlink’s promise is a shift in orbital strategy. Traditional satellite internet relied on geostationary satellites positioned about 36,000 kilometers above Earth. At that altitude, satellites remain fixed relative to the planet’s surface, making them easy to track with ground dishes. But the distance introduces a fundamental physical problem. Signals traveling at the speed of light still take a noticeable fraction of a second to make the round trip, leading to high latency. For activities like video calls, online gaming, or real-time collaboration, this delay can be frustrating or even disabling.

Starlink uses low Earth orbit satellites instead, flying at altitudes of roughly a few hundred kilometers. At these distances, the signal delay drops dramatically, approaching the responsiveness of terrestrial broadband. The trade-off is complexity. Satellites in low Earth orbit move rapidly across the sky, completing an orbit in about ninety minutes. To provide continuous coverage, thousands of satellites must work together, handing off connections seamlessly as they pass overhead.

From a physics perspective, this is a remarkable feat. Each satellite communicates with user terminals on the ground using radio frequencies carefully chosen to balance bandwidth, atmospheric interference, and regulatory constraints. Advanced phased-array antennas electronically steer beams without moving parts, tracking satellites as they race across the sky. In newer generations, satellites communicate with each other using laser links, routing data through space rather than relying solely on ground stations.

The result is a global, space-based mesh network, dynamically reconfiguring itself in real time. It is an internet not anchored to the Earth, but floating above it.

Starlink’s Early Impact: Promise Meets Reality

Since its initial deployments, Starlink has delivered on many of its technical promises. Users in remote regions have reported speeds comparable to urban broadband, with latency low enough for video conferencing and online gaming. During natural disasters, when terrestrial networks fail, satellite internet has provided critical connectivity. In conflict zones and isolated areas, it has enabled communication where none existed before.

These successes have fueled a narrative of inevitability, a sense that the digital divide is finally on the verge of collapse. Yet reality is more complex. Starlink’s service is not free, and the cost of user equipment and monthly subscriptions remains out of reach for many of the world’s poorest communities. Even where coverage exists, affordability can be a barrier as formidable as geography.

Moreover, satellite internet does not exist in a vacuum. It must coexist with national regulations, spectrum allocations, and political realities. Some governments welcome Starlink as a tool for development and resilience. Others view it with suspicion, concerned about sovereignty, security, and control over information flows.

The question is no longer whether satellite internet can work, but for whom it works, and under what conditions.

The Economics of Connectivity from Orbit

Building and maintaining a satellite constellation is enormously expensive. Rockets must launch satellites by the hundreds, ground infrastructure must be built, and constant monitoring is required to avoid collisions and manage orbital debris. Starlink’s business model relies on economies of scale, spreading these costs across millions of users worldwide.

This approach challenges traditional telecom economics. Instead of investing heavily in local infrastructure for each region, a single global system serves many markets simultaneously. In theory, this could lower costs and enable cross-subsidization, where revenue from wealthier users helps support access in poorer areas.

In practice, achieving this balance is difficult. Market forces still apply. Companies must satisfy investors, manage operational costs, and compete with terrestrial providers where they exist. There is no inherent guarantee that satellite internet providers will prioritize the most underserved communities unless incentives or policies encourage them to do so.

This raises an uncomfortable truth. Technology alone cannot solve the digital divide. It can expand the range of what is possible, but social and economic structures determine who benefits.

Beyond Starlink: A Growing Orbital Ecosystem

Starlink is not alone in its ambition. Other companies and organizations are developing their own low Earth orbit constellations, each with different technical approaches and strategic goals. Some aim to complement terrestrial networks, others to compete directly with them. Together, they represent a shift toward a multi-layered internet architecture, combining fiber, wireless, and satellite links into a more resilient whole.

This diversity matters. Competition can drive innovation, reduce costs, and prevent any single actor from dominating global connectivity. It can also create redundancy, ensuring that communication remains possible even when one system fails.

From a scientific standpoint, the proliferation of satellites presents new challenges. Orbital congestion increases the risk of collisions, which can generate debris that threatens other spacecraft. Managing this environment requires precise tracking, coordinated maneuvering, and international cooperation. The physics of orbital mechanics does not bend to market competition; all satellites share the same finite space around Earth.

Environmental and Astronomical Concerns

The rapid growth of satellite constellations has sparked concern among astronomers and environmental scientists. Bright satellites can interfere with astronomical observations, streaking across images of the night sky and complicating the study of distant galaxies. While mitigation measures such as darker satellite coatings have reduced visibility, the cumulative impact of tens of thousands of satellites remains uncertain.

There are also broader environmental questions. Rocket launches produce emissions, and the long-term effects of frequent launches on the upper atmosphere are still being studied. Satellites eventually reenter the atmosphere, burning up and depositing materials whose impacts are not fully understood.

These concerns do not negate the benefits of satellite internet, but they remind us that technological progress carries trade-offs. The challenge is to balance the urgent need for connectivity with stewardship of shared global resources, including the night sky itself.

Connectivity, Power, and Control

Internet access is not just about speed and coverage. It is about power. Who controls the infrastructure? Who decides what content is accessible? Who can shut the network down, and under what circumstances?

Satellite internet complicates these questions. A constellation operating across borders can bypass local infrastructure and, in some cases, local control. For individuals living under restrictive regimes, this can be liberating, providing access to information and communication channels otherwise blocked. For governments, it can feel threatening, undermining regulatory authority.

This tension reflects a deeper issue at the heart of the digital divide. Connectivity empowers individuals, but it also challenges existing power structures. Satellite internet does not merely deliver data; it reshapes relationships between citizens, states, and corporations.

Whether this shift leads to greater freedom or new forms of dependency depends on governance, transparency, and accountability. Technology sets the stage, but society writes the script.

The Science of Latency and the Human Experience

Latency is often discussed in milliseconds, but its impact is felt emotionally. A delayed video call disrupts conversation, breaking the rhythm of human connection. An unresponsive interface creates frustration and disengagement. In education and healthcare, latency can be the difference between effective interaction and failure.

Low Earth orbit satellite internet reduces latency to levels that feel natural to users. This matters because the internet is increasingly interactive. It is not just about downloading information, but about participating in real-time communities, collaborating across distances, and forming relationships.

From a neuroscientific perspective, humans are highly sensitive to timing. Our brains evolved to interpret subtle delays in communication as cues. Reducing latency helps digital interactions align more closely with our social instincts, making remote connections feel more human.

In this sense, the physics of satellite orbits intersects with psychology and culture. Faster signals do not just transmit data more efficiently; they shape how we relate to one another across space.

Education, Healthcare, and Opportunity

One of the strongest arguments for satellite internet as a tool to bridge the digital divide lies in its potential impact on education and healthcare. In remote regions, teachers can access training, students can attend virtual classes, and educational resources can reach communities previously isolated. In medicine, telehealth can connect patients to specialists, enable remote diagnostics, and support emergency response.

These benefits are not hypothetical. They are already being realized in places where satellite internet has been deployed effectively. Yet success depends on more than connectivity alone. Devices, digital literacy, language, and cultural relevance all play critical roles. An internet connection without support systems can leave people connected but still excluded.

Thus, satellite internet should be seen as an enabling infrastructure, not a standalone solution. It opens doors, but someone must help people walk through them.

The Myth of a Single Solution

It is tempting to frame Starlink and similar systems as the definitive answer to the digital divide, a technological silver bullet. History cautions against such narratives. Complex social problems rarely yield to single solutions, no matter how elegant the engineering.

The digital divide arises from intersecting factors: economic inequality, education gaps, political decisions, and historical patterns of development. Satellite internet addresses one dimension, physical access, with remarkable effectiveness. But it does not automatically resolve issues of affordability, skills, or meaningful use.

Recognizing this does not diminish the achievement of satellite internet. It places it in context, as one powerful tool among many. Fiber networks, mobile broadband, community networks, and policy reforms all have roles to play.

A Glimpse of the Future Internet

Looking ahead, the internet may become more decentralized and resilient, woven from multiple layers of connectivity. Satellites in low Earth orbit could provide global coverage, while terrestrial networks deliver ultra-high speeds in dense areas. Intelligent routing could send data along the fastest or most reliable path at any moment, whether through fiber, air, or space.

Advances in satellite technology may further reduce costs, increase capacity, and improve efficiency. New materials, better propulsion systems, and more sophisticated software could make constellations safer and more sustainable. At the same time, international frameworks may evolve to manage orbital space responsibly.

In this future, connectivity might become less dependent on geography, narrowing one of the most stubborn dimensions of inequality. But achieving that vision will require deliberate choices, guided by values as much as by engineering.

Is Satellite Internet the End of the Digital Divide?

The honest answer is both hopeful and cautious. Satellite internet, exemplified by Starlink, represents a genuine breakthrough. It has already connected people who were previously unreachable by conventional means. It demonstrates that physics and ingenuity can overcome barriers once thought insurmountable.

Yet the digital divide is not only a technical gap; it is a social one. Ending it requires aligning technology with human needs, ensuring affordability, protecting rights, and investing in education and inclusion. Satellite internet can light the path, but it cannot walk it alone.

Perhaps the most profound impact of Starlink and its successors is not the data they transmit, but the shift in imagination they inspire. They remind us that the limits of connectivity are not fixed, that the sky itself can become infrastructure, and that solutions to global challenges may come from unexpected directions.

As satellites trace silent arcs across the night sky, they carry more than signals. They carry a question that belongs to all of us: will we use this extraordinary capability to truly connect humanity, or will old divides persist beneath new constellations? The answer, like the internet itself, will be shaped not only by technology, but by the choices we make together.