Most of us think we know sloths. The image is iconic—furry, sleepy-eyed creatures suspended from rainforest branches, moving at the speed of molasses, digesting meals over the course of weeks, and defecating with comedic rarity. They’ve become the mascots of laziness, the poster animals for chill. But this modern portrayal hides a wildly diverse and ancient past.

Beneath the leaves of evolutionary history, the modern sloth is just a twig on a once-mighty branch. Only two species survive today—the three-toed and two-toed sloths—but they’re the final whisper of a lineage that once thundered across ancient landscapes. Their ancestors were not all tree-dwellers, nor were they small. In fact, some were titans of the Ice Age, behemoths that rivaled elephants in size and bore claws the length of butcher knives. From cliffside latrines in the Grand Canyon to underwater grazers along the Peruvian coast, sloths were once among the most remarkable mammals to walk—or waddle—the Earth.

Now, thanks to a groundbreaking study published in Science, we’re beginning to understand not only how these creatures grew so enormous, but why only a miniature fraction of their kind survived.

A Lost Menagerie: Sloths Like You’ve Never Imagined

If sloths seem like an evolutionary joke—a mammal that decided to be as slow as possible and somehow survived—it’s only because we’re seeing the end of the story, not the whole tale. Their closest relatives are anteaters and armadillos, and if that seems like a strange family reunion, paleontology agrees. Sloths once came in an astonishing variety of shapes and sizes: some had long snouts built for sniffing out insects; others looked more like shaggy tanks.

The heavyweight champion of the sloth world was Megatherium, a genus of ground sloths that reached the size of an Asian bull elephant. Weighing in at an estimated 8,000 pounds and standing over 12 feet tall when rearing on hind legs, these were not your average tree-clingers. They looked like fur-covered grizzly bears magnified five times over, and their anatomy was tailored to terrestrial dominance. Their powerful claws could tear down trees or excavate caves, and their long, dexterous tongues allowed them to strip high branches of leaves, functioning as prehistoric analogs to giraffes.

Another member of the diverse sloth cast was the Shasta ground sloth, far smaller than Megatherium but still a beast by modern standards. It roamed the deserts of North America, chewing on cacti and making dens in wind-carved caves. In some cases, these caves doubled as communal toilets. A 1936 excavation of Rampart Cave in Arizona uncovered over 20 feet of fossilized feces, bat guano, and midden material—evidence of long-term sloth occupation.

These weren’t fringe creatures eking out an existence—they were ecosystem engineers. So why did some sloths get so massive, while others stayed relatively small? And why did nearly all of them vanish?

Sizing Up the Puzzle: Why Giant Sloths Got So Big

You don’t need to be an evolutionary biologist to understand why modern sloths are small. Living in trees places a strict weight limit on a species. The higher you climb, the more dangerous gravity becomes, and tree branches only support so much mass. Falls are frequent for today’s arboreal sloths, and while some have survived plummets of up to 100 feet, evolution has favored smaller, lighter individuals. The average tree sloth today weighs just around 14 pounds.

But on the ground, gravity works differently. There’s no risk of falling, and being large can offer numerous advantages—thermoregulation, predator deterrence, foraging range. Scientists long suspected size was tied to survival, but understanding the full story meant answering multiple interlocking questions: Were giant sloths just closely related to one another, inheriting size from a common ancestor? Or did size evolve independently across different lineages? Did their environments dictate their dimensions? What about climate? What about diet?

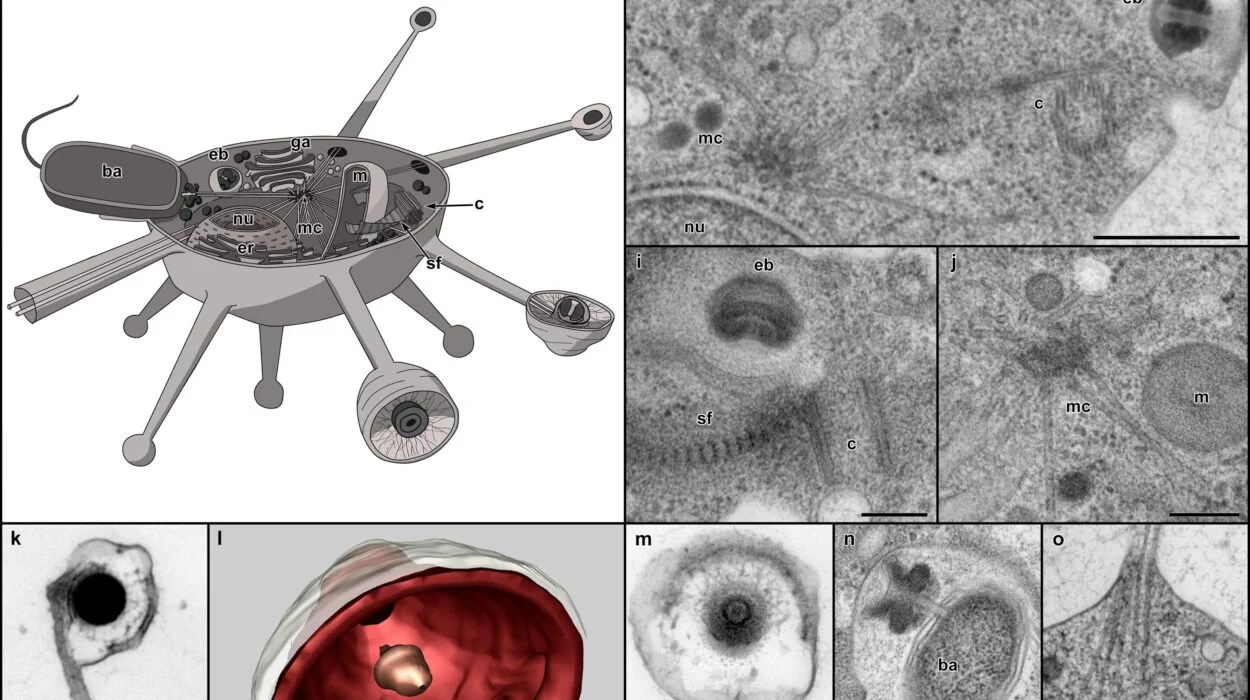

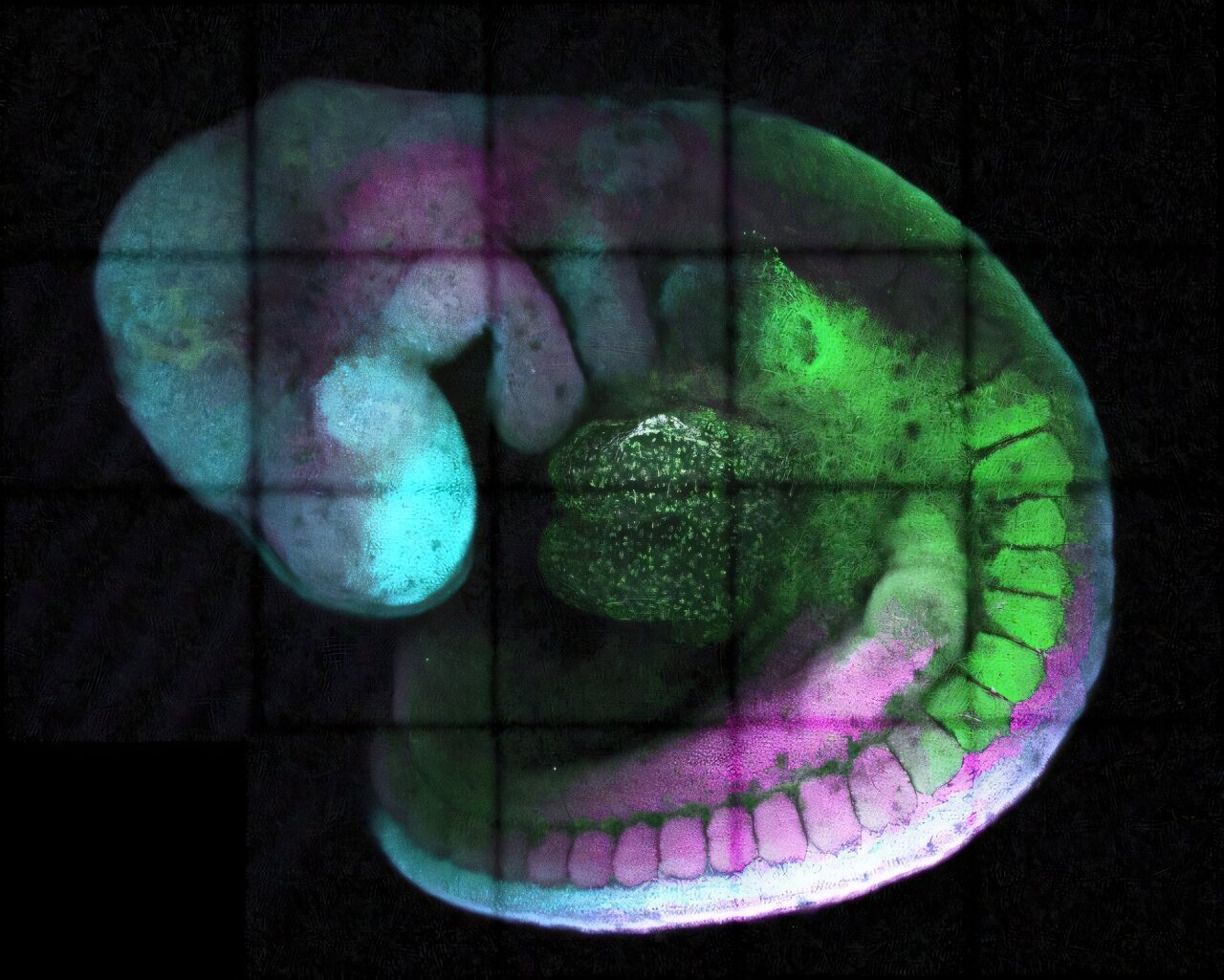

To get answers, researchers undertook a massive project that integrated fossil data, ancient DNA, ecological modeling, and evolutionary algorithms. More than 400 fossil specimens from 17 museums were examined. DNA from both living and extinct sloths helped construct a robust “sloth family tree” stretching back 35 million years.

Florida Museum of Natural History’s Rachel Narducci, co-author of the study, played a key role. Her institution houses the world’s largest collection of North American and Caribbean sloths. She measured 117 fossil limb bones to help reconstruct ancient sloth body sizes. Then, computational models helped map these traits onto evolutionary scenarios. The results weren’t just informative—they were transformative.

The Climate Connection: How Earth’s Shifting Temperature Reshaped Sloth Evolution

The big revelation: sloth size was primarily shaped by habitat type and climate. Wherever climates shifted, sloths adapted—in remarkable and sometimes contradictory ways.

The earliest sloths, emerging in South America around 37 million years ago, were small terrestrial creatures. As global temperatures fluctuated, so did the availability of forests and grasslands, shaping sloth lifestyles accordingly. For nearly 20 million years, sloth body size remained relatively stable. Then, about 15 million years ago, everything changed.

A colossal volcanic event ripped through what is now the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Lava flowed for hundreds of thousands of years, releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This geological catastrophe triggered the Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum, a prolonged period of global warming. The Earth became wetter, forests expanded—and sloths shrank.

With more trees available, smaller, arboreal sloths gained an edge. Heat itself may have played a role, too—smaller animals lose heat more easily, an evolutionary perk in a warmer world.

But this warm period didn’t last. As Earth gradually cooled again, sloths began bulking up once more. Larger bodies conserve heat better and allow for energy-efficient travel over long distances in sparse environments. This pattern accelerated during the Ice Ages, when glaciers spread and ecosystems fragmented. By the Pleistocene, sloths had reached their peak in size and geographical range.

Masters of Many Worlds: Sloths Conquer Land, Sea, and Sky (Almost)

Sloths weren’t just versatile in size—they were astonishingly adaptable in habitat. Arboreal sloths obviously needed trees, but ground sloths colonized nearly every terrestrial niche.

They climbed mountains in the Andes, grazed open grasslands in South America, wandered the deserts of the American Southwest, and even ventured into boreal forests in Canada and Alaska. Some became subterranean cave dwellers. Others—like the genus Thalassocnus—ventured into the sea.

Yes, sea sloths. These remarkable animals lived along the Peruvian coast and developed traits reminiscent of manatees and dugongs: dense bones to aid in buoyancy control, elongated snouts for grazing underwater vegetation. They’re one of the few terrestrial mammal lineages to make a serious go at aquatic life.

In dry regions, ground sloths adapted in other ways. To conserve energy and water, many species bulked up. Bigger bodies held more reserves. Their thick skin sometimes featured bony plates called osteoderms—a trait they shared with their armadillo cousins and that likely offered some protection from predators.

But perhaps their most impressive feat was geographic range. Sloths were among the few South American species to migrate north following the formation of the Isthmus of Panama three million years ago. This land bridge sparked the Great American Biotic Interchange, a massive cross-continental exchange of fauna. Sloths held their own against saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, and short-faced bears.

For a time, it seemed like nothing could stop them.

Fall of the Giants: The End of the Ground Sloths

The sloth heyday came to a sudden, tragic end about 15,000 years ago. The Ice Age was waning, and a new species was entering the Americas: humans.

While climate shifts may have stressed some sloth populations, evidence increasingly suggests that human arrival was the coup de grâce. The largest and slowest ground sloths would have been easy prey—massive, defenseless, and predictable. Once ecological monarchs, they became meals.

Their extinction wasn’t isolated. North America lost more than 70% of its large mammal species in a geologically brief window. The Caribbean held out a little longer—two species of tree-dwelling sloths persisted there until about 4,500 years ago. Their end came not long after humans arrived, around the time Egyptians were building pyramids.

Only two tree-dwelling species survived. Perched high in the canopy, they watched the collapse of their kind, evolving toward stillness and secrecy. Their sluggish metabolisms, once a punchline, became survival strategies in dwindling forests. Today’s sloths are ghosts of giants—living relics of an age when mammals ruled with claws instead of claws and teeth.

The Legacy of the Sloth: A Story Still Being Written

Though their world is gone, sloths continue to fascinate. Their evolutionary journey—an epic spanning tens of millions of years, multiple continents, and radical environmental upheaval—offers a glimpse into the incredible plasticity of life.

“Sloths aren’t just cute,” said Rachel Narducci. “They’re a lineage that adapted in extreme and diverse ways. And their story isn’t just about extinction—it’s about persistence.”

New technologies, especially ancient DNA analysis, are helping paleontologists like Narducci and her international team untangle the branches of the sloth family tree. What they’re discovering is not a tale of laziness, but one of resilience, innovation, and sometimes, just bad luck.

As we face another epoch of rapid climate change, the tale of the sloths may offer both a warning and an inspiration. Life adapts—but only so fast. And the giant ground sloths, once rulers of the land, remind us that even the most extraordinary creatures can vanish, leaving behind only fossils, claw marks, and the silence of vanished steps.

The modern sloth, dangling from a tropical branch, is not an evolutionary punchline. It is a survivor. And in its slow-motion movements, we glimpse the fading echo of a time when sloths weren’t just survivors—they were kings.

Reference: Alberto Boscaini et al, The emergence and demise of giant sloths, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adu0704. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adu0704