In the still hours of the night, while the world slumbers, something unseen is happening inside the adolescent brain. A quiet, invisible storm may be brewing—one that could shape a young person’s future far more profoundly than even the traumas they’ve endured or the genes they carry.

That’s the startling message emerging from a sweeping new study, published in Nature Medicine, which analyzed data from over 11,000 children and teenagers across the United States. The research, part of the ambitious Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, suggests that sleep disturbances may be the single most powerful predictor of who will go on to develop psychiatric disorders in the near future—more telling, even, than adverse childhood experiences or a family history of mental illness.

In a world where mental health conditions are on the rise and our understanding of prevention remains fragile, the findings offer a potential breakthrough. They also offer a poignant reminder: mental illness doesn’t always scream for attention—it sometimes whispers through a restless night.

A Shift in Medicine’s Frontier

For over a century, medicine has made astonishing progress in eliminating or taming the diseases that once terrorized humanity. Polio, typhoid, tuberculosis—once devastating—have been pushed to the margins through vaccines and antibiotics. But as these victories accumulated, a new frontier emerged: the silent, often invisible afflictions of the mind.

Mental health disorders now represent some of the most persistent and poorly understood challenges in modern medicine. Conditions like depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia are notoriously difficult to treat and even harder to predict.

That’s why researchers like Elliot D. Hill, the study’s lead author, are turning toward prevention—and asking one crucial question: Can we foresee mental illness before it strikes?

The Power of Prediction

To answer that, Hill and his team harnessed the power of machine learning—training artificial intelligence models on a mountain of biological and psychological data from thousands of young participants in the ABCD study.

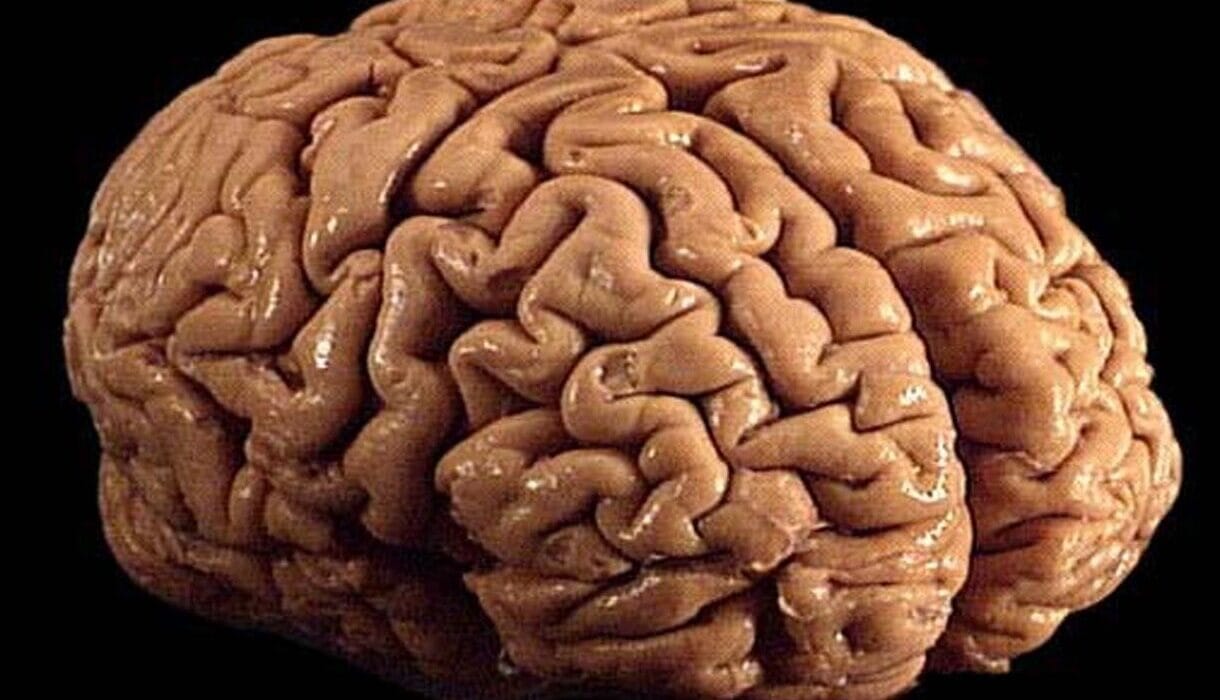

These adolescents, aged 9 to 15, had been followed for up to three years. During that time, they completed detailed psychosocial assessments, revealing insights into their family environments, stress levels, sleep habits, and current emotional symptoms. They also underwent MRI brain scans, offering a glimpse into the architecture of their developing minds.

The goal? To build predictive models that could identify which of these seemingly healthy young people were on a trajectory toward serious psychiatric conditions.

The results were illuminating—and surprising.

A Sleepless Signal

Among the many factors studied, one stood out again and again: sleep problems.

Sleep disturbances—trouble falling or staying asleep, restless nights, chronic fatigue—were the strongest and most consistent predictor of whether a young person would later be classified as high-risk for psychiatric illness. This was true even when accounting for trauma, socioeconomic stress, or mental health issues in the family.

“We were struck by how reliably sleep emerged as a warning light,” Hill said. “It appeared more powerful than nearly every other psychosocial factor we examined.”

What’s more, the researchers found that adding neuroimaging data—MRI scans of the brain—did not improve the models’ accuracy. This challenges the growing belief that brain scans can serve as diagnostic tools or early warning systems for mental illness. For now, it seems, the sleeping mind may reveal more through behavior than through pictures.

Why Sleep Might Matter So Much

The connection between sleep and mental health has long been known. Poor sleep can worsen mood, concentration, and emotional regulation—symptoms commonly seen in psychiatric disorders. But this study is among the first to suggest that sleep problems could precede and predict these disorders, rather than simply accompany them.

One theory is that sleep disruption in early adolescence destabilizes the brain’s emotional circuitry, making it more vulnerable to conditions like anxiety and depression. Others propose that poor sleep is a reflection of deeper, underlying stress that hasn’t yet surfaced in other ways.

Whatever the cause, the implication is clear: monitoring sleep may be one of the most effective tools we have for early mental health intervention.

A New Path for Prevention

What makes this research even more compelling is its practicality. The predictive models relied not on expensive lab tests or advanced imaging, but on readily available psychosocial questionnaires—tools that any school counselor or primary care provider could, in theory, administer.

The dream of a mental health “check-up”—a way to catch problems early, before they become life-altering—has long seemed out of reach. But artificial intelligence, paired with simple behavioral data, might bring that dream closer to reality.

“These findings suggest that AI models can effectively flag high-risk individuals using nothing more than a few questions about sleep, stress, and mood,” Hill said. “That could have profound implications for how we approach screening and early support.”

Hope With Caution

Still, the researchers are quick to add a note of caution. The models show correlation, not causation. Just because poor sleep is associated with higher risk doesn’t mean it causes psychiatric illness. And while predictive models are promising, they are not yet foolproof.

“This is an important step, but not a final answer,” said Hill. “More research is needed to refine these models and understand the mechanisms behind these patterns.”

And while the study focuses on youth, it resonates with broader questions about modern life. Today’s teenagers are chronically sleep-deprived, thanks to late-night screen time, academic pressure, and disrupted routines. If sleep truly is the canary in the coal mine, our society may be ignoring one of its loudest warning signals.

Listening to the Silence

In many ways, the study’s message is as old as parenting itself: watch how your child sleeps. But in an age of algorithms and artificial intelligence, that message now carries a new scientific weight.

When a teenager tosses and turns, when their eyes are puffy and their mornings sluggish, it might not just be hormones or homework. It might be the early signs of a mind in trouble—signs that are easier to treat before they evolve into something more serious.

For decades, mental health professionals have struggled to predict who will suffer and who will not. With this new research, that struggle may be entering a new phase—one that listens more closely, not just to what children say, but to how they sleep.

Because sometimes, the first sign of a storm isn’t thunder. It’s silence in the dark.