For decades, hormone-sensitive lipase — HSL — has been cast in a simple role: the molecule that gives fat cells permission to open their energy vault. When the body needs fuel, hormones such as adrenaline activate HSL, which then frees stored fat from adipocytes into the bloodstream. The logic seemed straightforward: without HSL, the fuel valve would close and fat would accumulate. But reality staged a quiet rebellion against that neat picture.

Patients born without HSL do not become obese. They lose fat. Their bodies cannot maintain adipose tissue, developing a severe form of lipodystrophy in which fat stores dwindle and dangerous metabolic complications follow. The same paradox was reproduced in mice. For years, no one could explain why a protein whose job is to liberate energy from fat would be required to preserve fat.

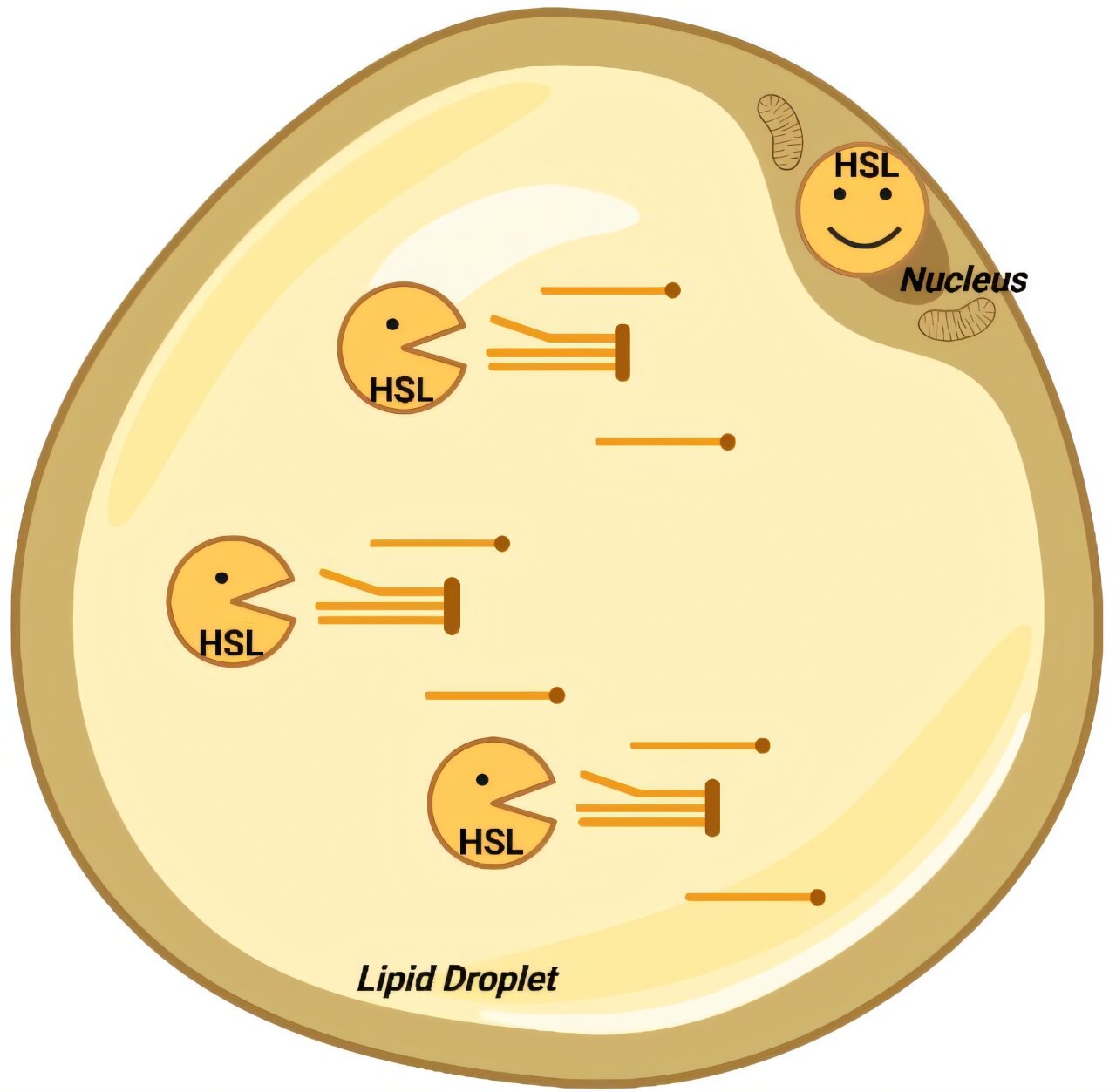

A team from the Institute of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Diseases in Toulouse has now cracked the riddle by finding a second, hidden life of HSL — not on the fat droplet surface, but deep inside the nucleus of adipocytes. The work, published in Cell Metabolism, reframes what it means for a fat cell to be healthy and what goes wrong in obesity and lipodystrophy alike.

Fat Cells as Guardians of Energy, Not Just Storage Sacks

Adipocytes are not passive balloons of grease. They are active endocrine cells, central to energy homeostasis. They stockpile calories as lipid droplets when food is plentiful and release them during fasting. HSL has long been known as the executor of that release — the biological switch that converts locked energy back into usable fuel.

When fasting or stress triggers adrenaline, HSL becomes an enzyme in action, chopping up lipids so that organs have something to burn. That kinetic, on-demand role made HSL famous; it has been described in textbooks since the 1960s. But focusing on this one function blinded researchers to a second job the enzyme quietly performs.

A Protein That Lives in Two Worlds

The Toulouse researchers mapped HSL inside human and mouse adipocytes and found that it is not confined to lipid droplets. It also resides in the nucleus — the command center that controls gene expression. In that second location, HSL is not cutting fat. It is interacting with other nuclear proteins and helping to maintain the genetic program that keeps adipose tissue viable.

That nuclear job turns out to be essential. Without HSL, adipocytes lose the instructions that sustain their identity and structure. They shrink, malfunction, and may even die. The body does not accumulate fat when HSL is missing — it loses the ability to be a proper fat-storing organ.

The paradox dissolves: HSL does not simply empty fat. It also helps fat cells exist.

The Double Regulation of HSL

The study also reveals a nuanced choreography. The same hormone — adrenaline — that sends HSL to lipid droplets during fasting also drives it out of the nucleus. When the body calls on adipocytes to release fuel, it temporarily shuts down their nuclear maintenance mode. In obesity, by contrast, the amount of HSL in the nucleus is abnormally high, as if fat cells are stuck in a chronic state of self-maintenance rather than flexible response.

This twin localization — on droplets to mobilize fat, in the nucleus to preserve fat cell health — means HSL is a bifunctional regulator. It is both executor and custodian, both switch and safeguard.

When Opposites Converge: Obesity and Lipodystrophy

Obesity and lipodystrophy appear to sit at opposite ends of the spectrum: too much fat versus too little. But their metabolic consequences — insulin resistance, inflammation, cardiovascular risk — are strikingly similar. The new findings suggest a shared root: improper function of adipocytes. When fat cells are unhealthy, whether swollen and dysfunctional or depleted and absent, systemic metabolism destabilizes.

By identifying HSL’s nuclear role, the Toulouse team provides a mechanistic bridge explaining why losing HSL leads to fat loss yet also to the same metabolic collapse seen in obesity. What matters is not the size of a person but the integrity of their adipose tissue.

Why This Discovery Matters Now

The timing is not incidental. Overweight and obesity affect half of adults in France and more than two and a half billion people worldwide. Obesity fuels diabetes, heart disease, liver disease, infertility, sleep apnea, and cancers. Lipodystrophy, though rarer, is equally dangerous. In both settings, treatment is still imperfect because the biology of adipose tissue is not fully understood.

The new insight that a decades-old enzyme has a second, nuclear life changes the conceptual map. It suggests that future therapies might target not only fat breakdown but fat cell maintenance. It reframes adipose tissue not as a passive insult to health but as an active organ whose stability or breakdown dictates metabolic fate.

A Second Life, A New Beginning

In science, the biggest shifts often come not from discovering a new molecule but from realizing that an old one meant something different all along. HSL was known as a molecular ax that splits fat. It turns out to be a steward of cellular identity. That discovery rewrites a chapter in metabolic biology and opens new avenues for understanding — and eventually treating — a global epidemic whose roots run through the health of a single cell type.

The story of HSL is a reminder that biological truth is rarely one-dimensional. What saves us in one context may destroy us in another. What mobilizes energy may also guard the cell that stores it. And what looks like a paradox is often an undiscovered layer of order waiting to be seen.

More information: Nuclear Hormone-sensitive Lipase Regulates Adipose Tissue Mass and Adipocyte Metabolism, Cell Metabolism (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2025.09.014. www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/f … 1550-4131(25)00433-4