The story of the Black Death has always felt like a catastrophe that arrived out of nowhere, a sudden dark wave that swept across medieval Europe without warning. But new research suggests its opening chapter may have begun in the sky, not in a port city or a crowded marketplace. It may have begun with a volcanic eruption no one ever realized had happened.

Two researchers studying tree rings—nature’s careful record keepers—found clues that point to an extraordinary chain reaction. Their discovery hints that the deadliest pandemic in human history may have started with a moment of planetary darkness that set the rest of the tragedy into motion.

Summers That Should Not Have Been

The scientists focused on tree rings from the Pyrenees, the rugged mountain range straddling Spain and France. Tree rings do not lie. In the width of their bands, they record seasons of abundance or seasons of stress. When the researchers examined the rings from the years 1345 to 1347, they found something striking. The trees showed evidence of unusually cold and wet summers, a pattern that matched no ordinary climate fluctuation.

To understand why, the researchers compared their findings with written accounts preserved from the same period. The stories aligned. Temperatures had dropped. Sunlight had dimmed. The most likely explanation, they concluded, was that one or more volcanic eruptions had filled the atmosphere with particles in 1345, blocking solar radiation and cooling the region.

It was the first domino. A shift in the air that no one could see, yet everyone would feel.

The First Signs of Trouble

Cold and wet summers sound harmless enough—an inconvenience, perhaps a memorable season or two. But in the tightly balanced agricultural world of medieval Europe, they spelled disaster. Crops failed. Harvests spoiled. Food stores shrank faster than they could be replenished. What began as a climate anomaly quickly grew into the early stages of a famine.

In those moments, southern Europe found itself standing at a crossroads. The climate had thrown them into danger. Yet human ingenuity offered a path toward safety.

A Lifeline Across the Water

Southern Europe at the time was home to powerful Italian city states, societies that thrived on the art of trade. Venice, Genoa and Pisa had woven together long-distance routes that stretched across the Mediterranean and deep into the Black Sea. When famine loomed, these networks became a lifeline.

“Powerful Italian city states had established long-distance trade routes across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, allowing them to activate a highly efficient system to prevent starvation,” said Martin Bauch, a historian at Germany’s Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe.

Ships began to ferry grain from the Mongols of the Golden Horde in central Asia. It was a clever solution, born from centuries of building connections across continents. For a moment, it seemed Europe had escaped the worst.

“But ultimately, these would inadvertently lead to a far bigger catastrophe,” Bauch added.

The lifeline would become the opening gate.

Deadly Travelers Hidden in the Hulls

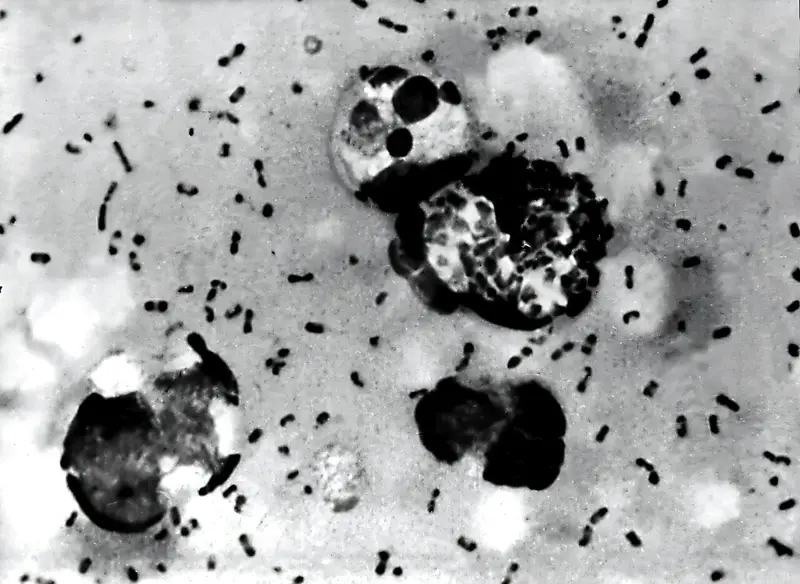

For years, researchers have suspected that grain ships from central Asia brought more than food. Among the sacks of grain and coils of rope, there were silent passengers. Rats. And on those rats were fleas. And in those fleas was Yersinia pestis.

The bacterium that causes plague.

The new study does not alter that central narrative. Instead, it reveals the underappreciated spark that set it all in motion. If the volcanic eruptions of 1345 had not triggered cold summers, and if those summers had not wrecked the harvests, there may have been no urgent need for so many ships to travel such great distances at exactly the wrong time.

The city states were trying to solve a crisis. Instead, they opened the door to the one that would define the century.

Between 25 and 50 million people are estimated to have died over the next six years. Whole communities disappeared. Entire regions were undone. The Black Death reshaped Europe culturally, demographically and economically. And according to these tree rings, the seed of that sweeping tragedy was planted by nature’s sudden atmospheric shadow.

A Chain Reaction Across Nature and Civilization

The researchers emphasize that the events surrounding the Black Death were never simple. The plague’s arrival and expansion involved intertwined strands of natural forces, human choices, political structures and economic networks. Yet the study’s authors argue that the previously unidentified eruption deserves a place in the story as the moment that tipped the first stone.

“Although the coincidence of factors that contributed to the Black Death seems rare, the probability of zoonotic diseases emerging under climate change and translating into pandemics is likely to increase in a globalized world,” study co-author Ulf Buentgen of Cambridge University in the UK said in a statement.

“This is especially relevant given our recent experiences with COVID-19.”

It is a sobering reminder. A disturbance in climate, even one far from human eyes, can spark changes that ripple unpredictably through ecosystems, economies and societies. And in a world more interconnected than medieval Europe could have imagined, those ripples can travel even faster.

Why This Research Matters

The story uncovered in the Pyrenees tree rings is not merely a historical curiosity. It reshapes how we understand one of humanity’s greatest tragedies and offers a warning for the future. By showing how a hidden volcanic eruption likely disrupted climate, triggered famine, accelerated trade and helped unleash a pandemic, the study highlights the fragile connections between Earth’s systems and our own.

It reminds us that pandemics do not arise in isolation. They emerge from intersections—between climate and ecology, between human networks and natural forces, between decisions and circumstances. In the case of the Black Death, a dimmed sky may have set humanity on a path no one could have foreseen.

Understanding that chain of events matters deeply today. In a warming and increasingly interconnected world, small disturbances can once again cascade into global crises. The past may not repeat itself exactly, but it can teach us how to see the warning signs hiding in the world around us.

More information: Climate-driven changes in Mediterranean grain trade mitigated famine but introduced the Black Death to medieval Europe, Communications Earth & Environment (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02964-0