For years, scientists at the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center had been chasing a mystery. Prostate cancer, even when treated with the most advanced drugs, often found a way to adapt. Tumors that once depended on androgen receptor signaling would suddenly shed that identity and slip into a new form that the drugs could not touch. It was as if the cancer had learned to shape-shift.

This strange behavior, known as lineage plasticity, had long intrigued Michael Shen, Ph.D., co-leader of the Tumor Biology and Microenvironment research program. His career had been built on trying to understand how cancer cells reinvent themselves. And yet one question remained stubbornly unanswered. What exactly gives prostate cancer cells the power to transform into a drug-resistant state?

“Plasticity is a hallmark of cancer in general and a very important feature of advanced prostate cancer, particularly when it comes to the emergence of treatment resistance,” says Shen. But understanding the phenomenon was one thing. Stopping it was another.

The Clue That Changed Everything

Several years earlier, Jia Li, then a postdoctoral fellow in Shen’s lab, had uncovered an important piece of the puzzle. The shift into a neuroendocrine state—the drug-resistant form of the cancer—wasn’t triggered by a mutation. It wasn’t coded into the DNA at all. Instead, the cells were rewriting themselves through epigenetic changes, altering how their genes were expressed without altering the underlying genetic script.

This finding redirected the search. If the DNA wasn’t changing, something else must be orchestrating the transformation. Shen reached out to another scientist whose work touched exactly that frontier: Chao Lu, Ph.D., co-leader of the Cancer Genomics and Epigenomics research program.

“When Jia and Michael came to approach us, we definitely found this project very intriguing,” says Lu.

His lab specialized in the molecular markers that sit atop DNA—histones—tiny proteins that determine which genes are active and which stay silent. If prostate cancer cells were slipping into new identities, histone modifications were a likely culprit.

A Serendipitous Discovery

As Lu’s team profiled the epigenetic landscape of the cancer cells, something remarkable happened. The pathway controlling their shift from a typical prostate cancer identity to a neuroendocrine one was the very pathway Lu had been studying for years.

“It was quite satisfying that the pathway we have been working on ever since I came to Columbia was the one that came out as the top differentially regulated modification between neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine prostate cancers,” he says, adding that “we had no expectation of seeing this when we started.”

The discovery was thrilling, but it carried a challenge. The key enzyme involved—NSD2, a histone methyltransferase—had a notorious reputation. “The histone methyltransferase that we focused on, NSD2, had for many years been considered to be undruggable,” says Shen.

The obstacle was enormous. The science was compelling, but no journal wanted the story without proof that this supposedly undruggable enzyme could actually be inhibited. The team posted their findings on bioRxiv and waited for a breakthrough.

When Drug Development Caught Up

That breakthrough arrived unexpectedly from the pharmaceutical giant Novartis. The company had developed the first small molecules capable of inhibiting NSD2. Suddenly, the impossible became possible.

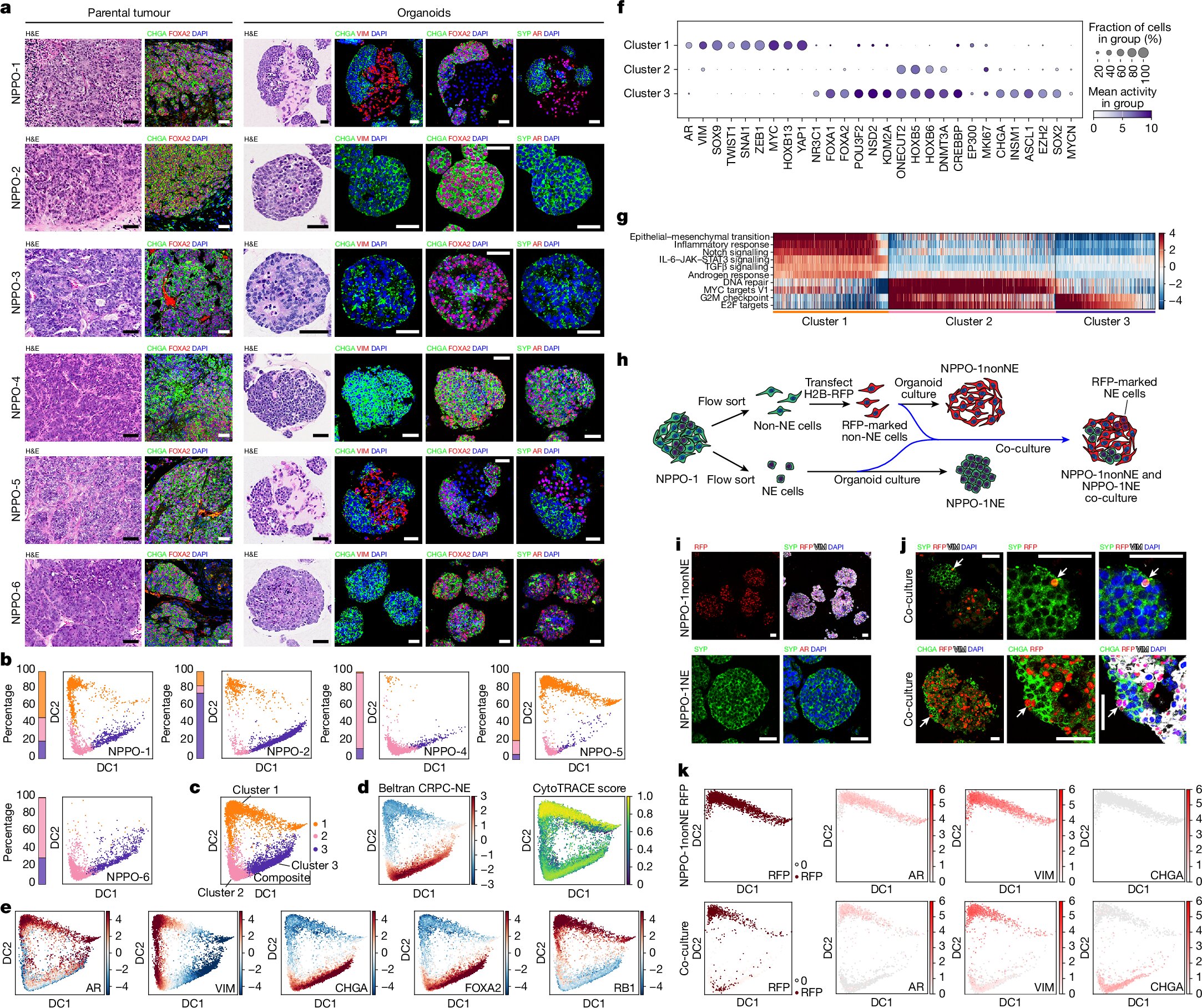

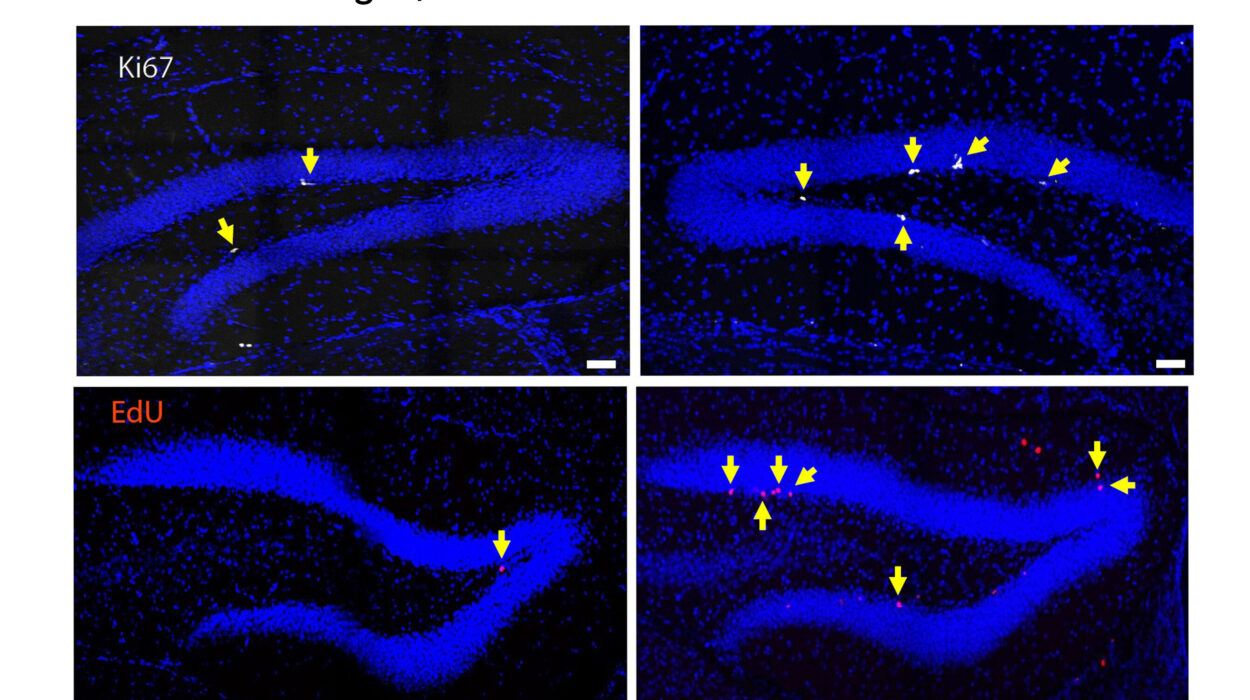

Shen, Lu, and their collaborators synthesized one of these inhibitors and tested it. What they found was striking. In organoids grown from prostate cancer cells, and in animal models, blocking NSD2 caused neuroendocrine tumors to shed the features that made them resistant. The tumors didn’t die from this alone, but something even more powerful happened. When the NSD2 inhibitor was combined with existing androgen receptor inhibitors, the two drugs worked together. One forced the cancer out of its drug-resistant disguise, and the other hit it in its newly vulnerable state.

The Moment the Tumor Turned Back

The most astonishing discovery came when the researchers tested the drug on tumors that had already transitioned into the aggressive neuroendocrine state. These cells had thoroughly abandoned their reliance on androgen signaling. They were, by all clinical standards, resistant.

But when NSD2 was blocked, those same tumors began to reverse course. They shifted back into a form that once again depended on androgen receptor signaling. They became sensitive to hormone therapy again.

This finding upended the idea that treatment resistance was a one-way road. The study showed that even highly aggressive, plasticity-driven tumors could be pushed back.

A New Possibility for Cancer Treatment

This research marks one of the first clear demonstrations that a certain form of treatment resistance in prostate cancer can be undone rather than simply avoided. The implications ripple far beyond a single disease. Lineage plasticity is not unique to prostate cancer; it appears in many aggressive tumors.

“We are already in collaborations to examine whether NSD2 plays a similar role in small cell lung cancer,” says Shen.

If the mechanism holds true across other cancers, it could reshape entire treatment strategies.

Why This Research Matters

Cancer’s greatest weapon has always been its ability to adapt. When one treatment fails, tumors find another path. For decades, the best scientists could do was outmaneuver cancer’s next move. But this study suggests something profoundly different. Instead of fighting cancer’s transformations, we may be able to reverse them.

The work from HICCC offers a new vision of cancer therapy, one in which resistance is not the end of the road. By targeting the epigenetic mechanisms that allow tumors to reinvent themselves, researchers may soon be able to reset cancers into a state where existing treatments work again.

It is not a cure, not yet. But it is a rare and hopeful shift in a field where progress is often measured by small, incremental gains. This discovery suggests something larger—a pathway not just to delay resistance, but to roll it back entirely.

More information: Jia J. Li et al, NSD2 targeting reverses plasticity and drug resistance in prostate cancer, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09727-z