For as long as neuroscience has tried to understand the brain, neurons have played the lead role in the story. They are the electrical performers, the cells that spark and signal. But behind them stand millions of quieter characters whose influence is no less profound. Among them, astrocytes—star-shaped and once overlooked—have suddenly become the subject of a sweeping new atlas created by researchers at MIT, revealing a world of diversity and motion that had been hiding in plain sight.

The new work uncovers how astrocytes vary from one brain region to another, how their identities shift across a lifetime, and how mice and marmosets, two pillars of neuroscience research, share or diverge in these patterns. The effort represents a massive attempt to chart these silent partners at a level never before seen. And as the findings unfold, a larger story emerges—one about how the brain’s supporting cells may be far more dynamic, specialized, and influential than anyone realized.

Where the Mystery Begins

The story starts with a question that Guoping Feng, the James W. (1963) and Patricia T. Poitras Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT, has been asking for years. “It’s really important for us to pay attention to non-neuronal cells’ role in health and disease,” he says. Despite growing evidence that astrocytes shape development, support neurons, and even contribute to psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders, he adds, “But compared to neurons, we know a lot less—especially during development.”

Astrocytes are not passive scaffolds. They help build neural circuits. They take part in information processing. They feed and protect neurons. And remarkably, they can change their roles as life unfolds. Yet scientists still lacked a clear understanding of how these cells differ from one part of the brain to another, or how their identities evolve from the earliest days of embryonic development through old age.

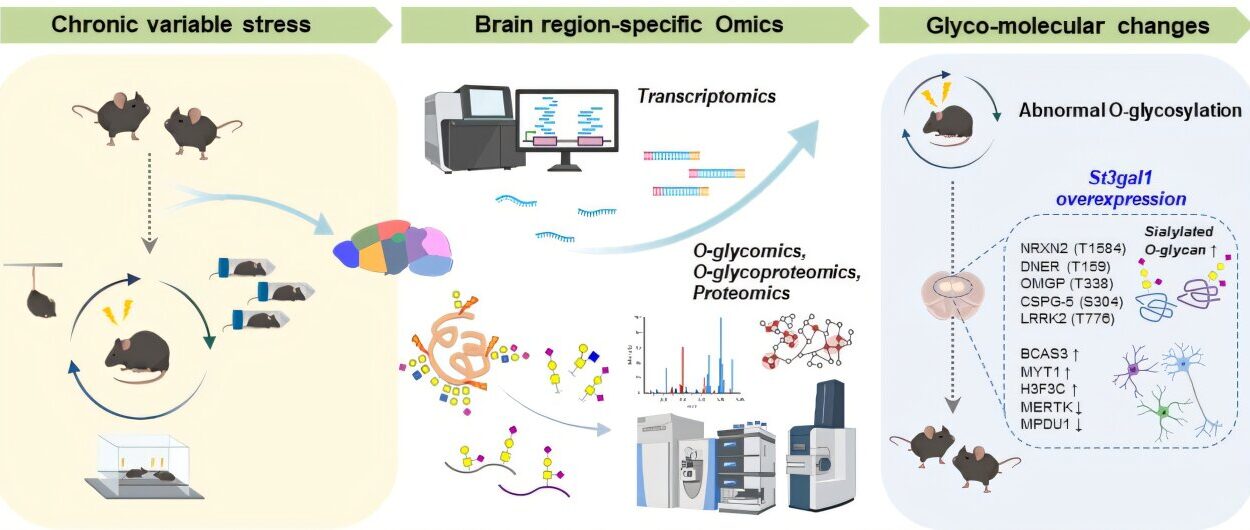

This is where Feng and Margaret Schroeder, then a graduate student in his lab, decided to push deeper. The pair wanted to examine astrocytes across three dimensions: space, time, and species. Their goal was ambitious—map how astrocytes vary across the brain, track how they change over the lifespan, and compare those patterns between mice and marmosets.

They knew from earlier work that adult animals show clear regional differences. “The natural question was, how early in development do we think this regional patterning of astrocytes starts?” Schroeder says. To answer it, they needed to capture the brain in motion.

The Long Journey Across a Lifetime

The team collected cells from mice and marmosets at six stages of life, spanning the arc from embryonic beginnings to old age. For each animal, they sampled four locations: the prefrontal cortex, the motor cortex, the striatum, and the thalamus. Working closely with collaborator Fenna Krienen—whose earlier research had helped set this project in motion—they analyzed the molecular contents of every sampled cell.

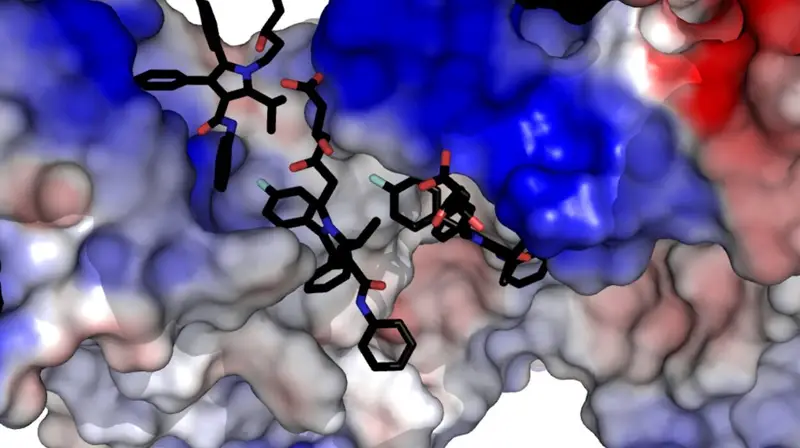

The key was the transcriptome, the set of mRNA molecules inside each cell that reveal which genes are active. A cell’s transcriptome is its identity card, showing what it is doing, what it is becoming, and how it communicates with its neighbors.

After examining the transcriptomes of about 1.4 million cells, the researchers zeroed in on astrocytes. And very quickly, a pattern emerged: location mattered.

At every stage of life, astrocytes from one brain region looked molecularly similar to each other—and distinct from those in other regions. This regional specialization was present even before birth. But something else was happening, too. Over time, astrocytes shifted again and again.

“When we looked at our late embryonic time point, the astrocytes were already regionally patterned. But when we compare that to the adult profiles, they had completely shifted again,” Schroeder says. “So there’s something happening over postnatal development.”

The most dramatic changes came between birth and early adolescence, a period when brains rapidly reorganize as animals encounter the world for the first time. During these years, neurons refine their connections, strengthen important pathways, and prune unnecessary ones. Astrocytes, it seems, are not bystanders. They are adapting alongside the neural circuits they support.

“What we think they’re doing is kind of adapting to their local neuronal niche,” Schroeder explains. “The types of genes that they are up-regulating and changing during development points to their interaction with neurons.”

Feng suggests the influence may flow both ways. Astrocytes may respond to nearby neurons, or they may help guide the development of those neurons, adopting identities tailored to the circuits they support.

The Shapes Behind the Shifts

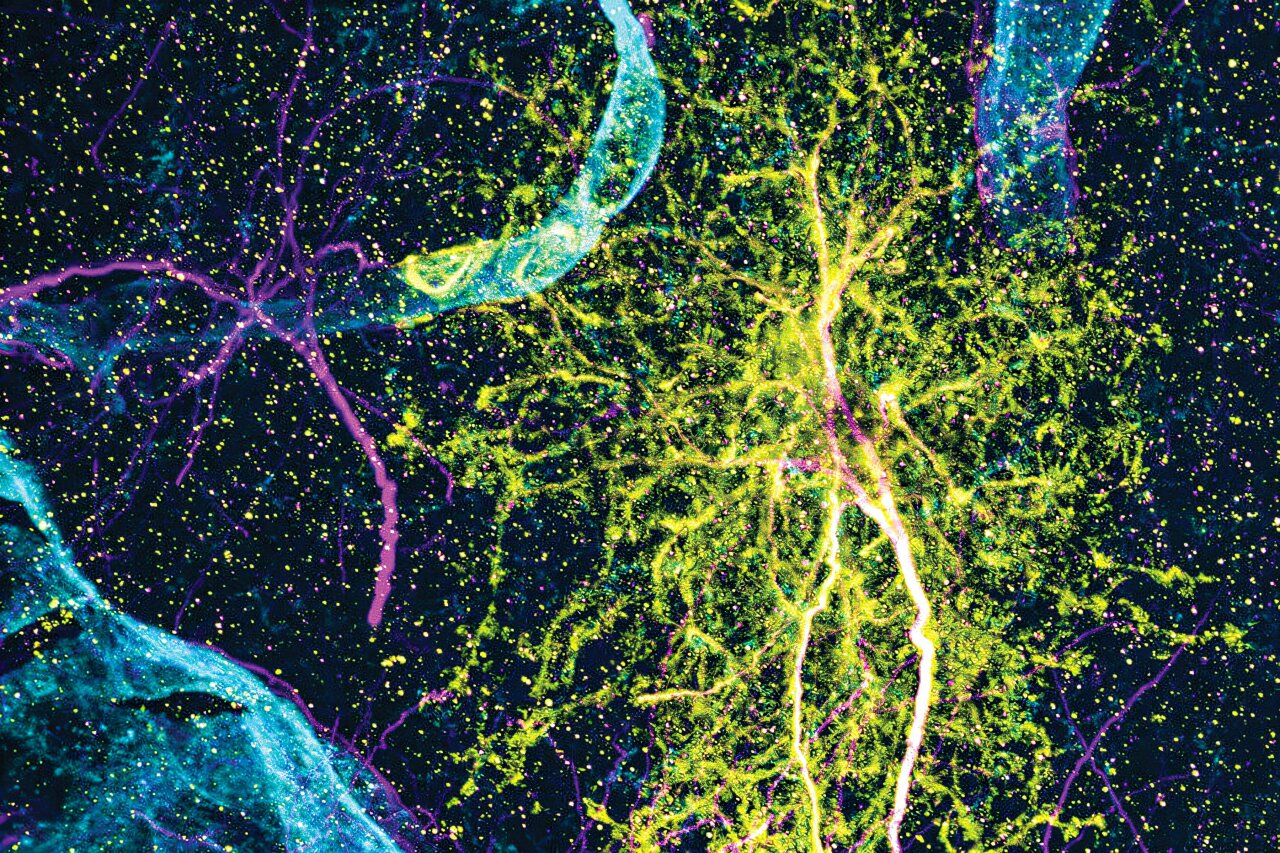

The story is not only molecular. Using expansion microscopy, a high-resolution imaging method developed by MIT colleague Edward Boyden, the researchers were able to visualize astrocytes in fine detail. Their shapes differed from one region to another, mirroring the unique genetic signatures found in each location.

These distinctive forms reinforced the idea that astrocytes are not generic support cells but specialized partners tuned to their surroundings.

A Tale of Two Species

Perhaps one of the most intriguing chapters came when the team compared mice and marmosets. Both species showed regional specialization. Both showed changes across time. But when the researchers looked closely at the individual genes that defined each astrocyte population, the similarities fell away.

Schroeder said this divergence should serve as “a note of caution” for scientists relying on animal models. While mice and marmosets both reveal the broad strokes of astrocyte behavior, the specifics may not always translate. That, she says, is exactly why the new atlas matters—it will help researchers gauge how relevant their findings may be across species.

What the Atlas Unlocks

The atlas is not the end of a story but the beginning of many more. Feng’s lab studies disease-related genes, and he says they now plan to examine how those genes affect astrocytes during different stages of development. The gene expression data can also help predict how neurons and astrocytes communicate, offering a roadmap for experiments exploring how these interactions shift with age or disease.

“This will really guide future experiments: how these cells’ interactions can shift with changes in the neurons or changes in the astrocytes,” Feng says.

And the data goes far beyond astrocytes. Schroeder points out that the team analyzed many kinds of brain cells. They are sharing everything, freely, so others can explore when and where particular genes are active or dive deeper into the brain’s cellular diversity.

Why This Research Matters

The brain is not just a network of neurons. It is a community, a dynamic interplay between many cell types working together across a lifetime. By revealing the diverse and changing identities of astrocytes, the MIT atlas opens a new window into how brains develop, adapt, and age.

Understanding astrocytes is essential for understanding health—and for confronting disease. These cells guide development, support neurons, and may contribute to disorders ranging from autism to neurodegeneration. With this new atlas, scientists now have a detailed, species-spanning map that shows not only where astrocytes live, but how they change, how they specialize, and how deeply they are woven into the fabric of brain function.

In the end, the study offers something rare: a view of the brain not as a collection of static parts, but as a living, shifting landscape. It reminds us that even the quietest cells can hold the keys to understanding how we learn, grow, age, and heal.

More information: Margaret E. Schroeder et al, A transcriptomic atlas of astrocyte heterogeneity across space and time in mouse and marmoset, Neuron (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2025.09.011