For decades, astronomers have looked up at the night sky with a quiet assumption in mind. Planetary systems, they believed, tend to follow a familiar blueprint. Close to the star, you find small, rocky planets. Farther out, in the colder reaches, drift massive gaseous worlds. It’s a pattern we know intimately from our own cosmic neighborhood, and one that seems to echo again and again across the Milky Way.

Or at least, it did.

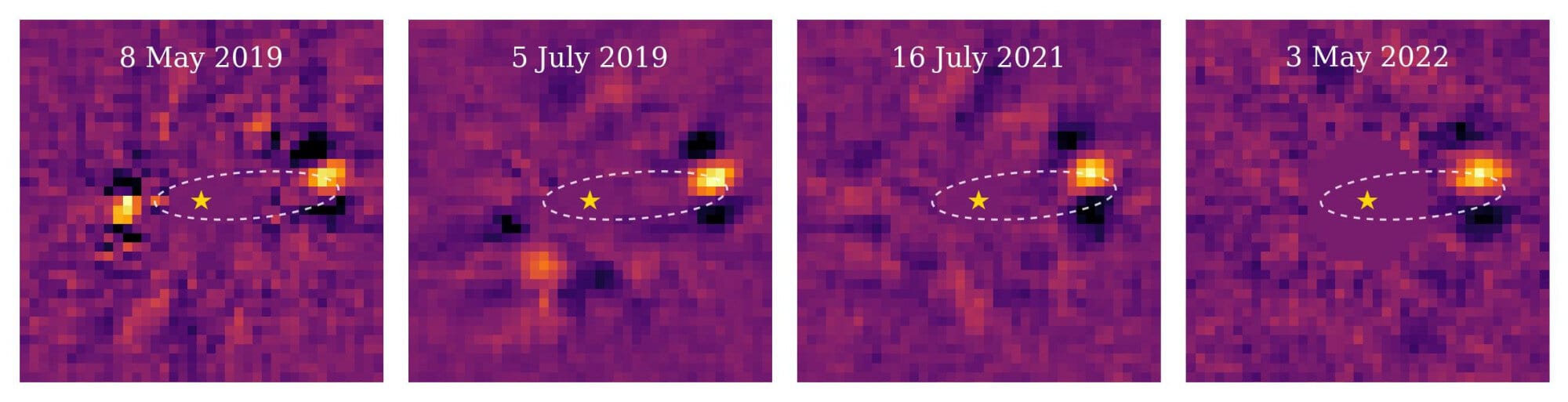

A global team of astronomers, led by the University of Warwick, turned their attention to a faint red dwarf star known as LHS 1903. Using the European Space Agency’s CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS), they uncovered something that doesn’t just bend the rules of planetary formation. It flips them inside out.

Their findings, published in Science, describe a planetary system so strange that it challenges one of astronomy’s most comfortable assumptions.

The Pattern We Thought We Understood

In our own Solar System, the story is clear. From Mercury to Mars, the inner worlds are small and rocky. Beyond them lie the giants: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, vast spheres made mostly of gas. This arrangement—rocky planets near the star, gaseous planets farther away—has long shaped our understanding of how planets form.

The reasoning behind it seems straightforward. According to traditional models, the intense radiation from a young star strips away lighter gases from nearby planets, leaving behind dense, rocky cores. Farther out, where it is cooler, gas can gather and remain. There, gas giants are born.

Over time, astronomers have observed this rock-then-gas sequence again and again in other planetary systems. It has felt almost universal.

Then came LHS 1903.

Four Worlds Around a Faint Red Sun

LHS 1903 is described as a cool, faint red dwarf star. Around it orbit four known planets. At first glance, the system seemed to follow the familiar script. Closest to the star is a rocky planet. Beyond it are two gaseous worlds. So far, so ordinary.

But when researchers examined the system more closely with CHEOPS, they spotted something astonishing at the outer edge.

The fourth and most distant planet was not gaseous.

It was rocky.

In other words, beyond two gas planets—farther from the star than both—orbited a small, solid world. A rocky planet sitting where a gas giant should be.

Dr. Thomas Wilson, Assistant Professor in the Department of Physics at the University of Warwick and lead author of the study, described it as a “unique inside-out system.” Rocky planets, he explained, don’t usually form far away from their home star, especially not beyond gaseous worlds.

This distant planet either lost its gaseous atmosphere somehow or never formed one at all. Either explanation would require something unusual.

And unusual is exactly what the team found.

A Puzzle That Wouldn’t Sit Still

Faced with this cosmic contradiction, the researchers began to test possibilities. Could the planets have switched places at some point in their history? Perhaps the rocky and gaseous worlds migrated, swapping positions in a gravitational dance.

Or maybe the outer rocky planet had once been cloaked in gas, only to lose it in a violent collision.

The team carefully examined these ideas and ruled them out.

What remained was something even more intriguing: the possibility that these four planets did not form together in a single sweeping moment of cosmic construction. Instead, they may have formed one after another, in sequence.

Born One by One in an Inside-Out Story

The researchers found evidence pointing toward a process known as inside-out planet formation. In this scenario, the planets of LHS 1903 did not emerge simultaneously from a swirling disk of gas and dust. They formed sequentially, beginning close to the star and moving outward.

Imagine the inner planet forming first. As it grows, it sweeps up nearby dust and gas, clearing its region. Then the next planet begins to take shape slightly farther out, evolving in a somewhat altered environment. This continues outward, each new planet forming in a disk that has already been changed by the birth of its predecessors.

By the time the fourth and outermost planet began forming, the system may have been nearly drained of gas.

Gas is considered vital for planet formation, especially for building gas giants. Yet this final planet appears to have formed in what Dr. Wilson described as a “gas-depleted environment.”

That detail may be the key to everything.

If the gas was already gone, the outermost planet would have had little opportunity to become a gaseous giant. Instead, it remained a small, rocky world—an unexpected outcome in an unexpected place.

This could represent the first evidence of a planet forming under such conditions.

A Late Bloomer in a Changed World

The outer rocky planet of LHS 1903 may have been a late arrival in a system that had already exhausted its resources. In that sense, it is a kind of cosmic late bloomer—forming after the grand spectacle of gas accumulation had already passed.

Rather than being stripped of its atmosphere, it may simply never have had one to begin with.

If this interpretation is correct, it suggests that planetary systems can evolve in stages, with each planet shaping the destiny of the next. The formation of earlier worlds alters the environment for those that follow.

In LHS 1903’s case, that sequential process may have rewritten the expected script entirely.

Rethinking What We Thought We Knew

For decades, our theories of planet formation have been shaped by what we see in our own Solar System. As Isabel Rebollido, Research Fellow at the European Space Agency, pointed out, these theories are rooted in familiar ground.

But the universe has a way of surprising us.

As more and more exoplanet systems are discovered, astronomers are encountering arrangements that don’t fit the mold. Systems that stretch, twist, and sometimes shatter our assumptions.

LHS 1903 may be one of those systems that forces a rethinking.

Maximilian Günther, CHEOPS project scientist at the European Space Agency, emphasized that much about how planets form and evolve remains a mystery. Clues like this one are exactly what missions like CHEOPS were designed to uncover.

Each unexpected discovery becomes a piece of a much larger puzzle.

Why This Discovery Matters

The rocky outer planet of LHS 1903 is more than a curiosity. It challenges a foundational idea in planetary science: that distance from a star largely determines whether a planet becomes rocky or gaseous.

If planets can form sequentially in an inside-out process, and if later planets can emerge in gas-depleted environments, then planetary systems may be far more dynamic and varied than once imagined.

This discovery hints that the architecture of planetary systems is not dictated by a single rigid rule. Instead, it may be shaped by timing, by sequence, and by the evolving conditions within a young stellar system.

In other words, the story of planet formation may not be a single, predictable blueprint repeated across the galaxy. It may be a series of unfolding chapters, where each planet writes part of the narrative for the next.

LHS 1903’s strange, inside-out system reminds us that the universe is not obligated to follow our expectations. It invites astronomers to revisit long-standing theories and to remain open to new patterns emerging from the data.

And perhaps most importantly, it underscores a profound truth about science itself. Every time we think we understand the rules, the cosmos presents a quiet, distant star—and a small, rocky planet where none should be—and asks us to look again.

Study Details

Thomas G. Wilson, Gas-depleted planet formation occurred in the four-planet system around the red dwarf LHS 1903, Science (2026). DOI: 10.1126/science.adl2348. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adl2348