Think back to one of the most vivid moments in your life. Perhaps it was the day you fell in love, the sound of a newborn’s first cry, or the sudden shock of bad news that left you breathless. These moments often feel more alive in our minds than others—a wedding remembered down to the scent of flowers, or the instant of a loss that still echoes years later. Psychology has long shown that emotion acts as a kind of spotlight for memory, illuminating some experiences so brightly that they remain etched in our minds for decades.

But while we have known that emotion makes memories more powerful, the reason why this happens has remained one of neuroscience’s most fascinating mysteries. How does the feeling of joy or fear physically change the way the brain records experience? Why do emotionally charged moments leave such an enduring mark on our minds?

A groundbreaking study by researchers at the University of Chicago and other institutes, recently published in Nature Human Behaviour, has begun to answer these questions. Their work reveals that emotional states enhance memory not by activating a single “memory center” in the brain, but by orchestrating a symphony of communication between many brain regions.

Emotions as the Glue of Experience

The senior author of the study, Yuan Chang Leong, describes emotional memories as “sticky.” Emotional experiences, he explains, don’t simply pass through the mind; they linger, shaping how we see the past, how we react in the present, and even how we imagine the future. To explore this phenomenon, Leong and his colleagues used a creative approach: they studied how people’s brains responded while watching emotional movies or listening to emotionally rich stories.

This method, both cinematic and scientific, offered a window into how complex emotions—like empathy, fear, or suspense—affect the brain’s memory systems. “Movies and stories weave together characters, sensory cues, and emotional arcs much like real life does,” Leong noted. By studying these naturalistic experiences, the researchers could trace how real emotional engagement alters the brain’s patterns of activity.

The Experiment Behind the Discovery

Instead of conducting a brand-new experiment, the team drew from publicly available datasets collected in previous studies. Participants in those earlier experiments had watched films or listened to stories while their brain activity was recorded using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). As they watched, their pupils were also tracked—a subtle window into emotional arousal, since our pupils widen when we are emotionally engaged or surprised.

Later, the same participants were asked to describe what they had seen or heard. Some scenes—like a character caught hiding a body—were rated as highly emotional or suspenseful, while others were calm and neutral. Using natural language processing (NLP) models, a form of artificial intelligence designed to analyze and interpret language, the team could quantify the emotional intensity of each moment in the story.

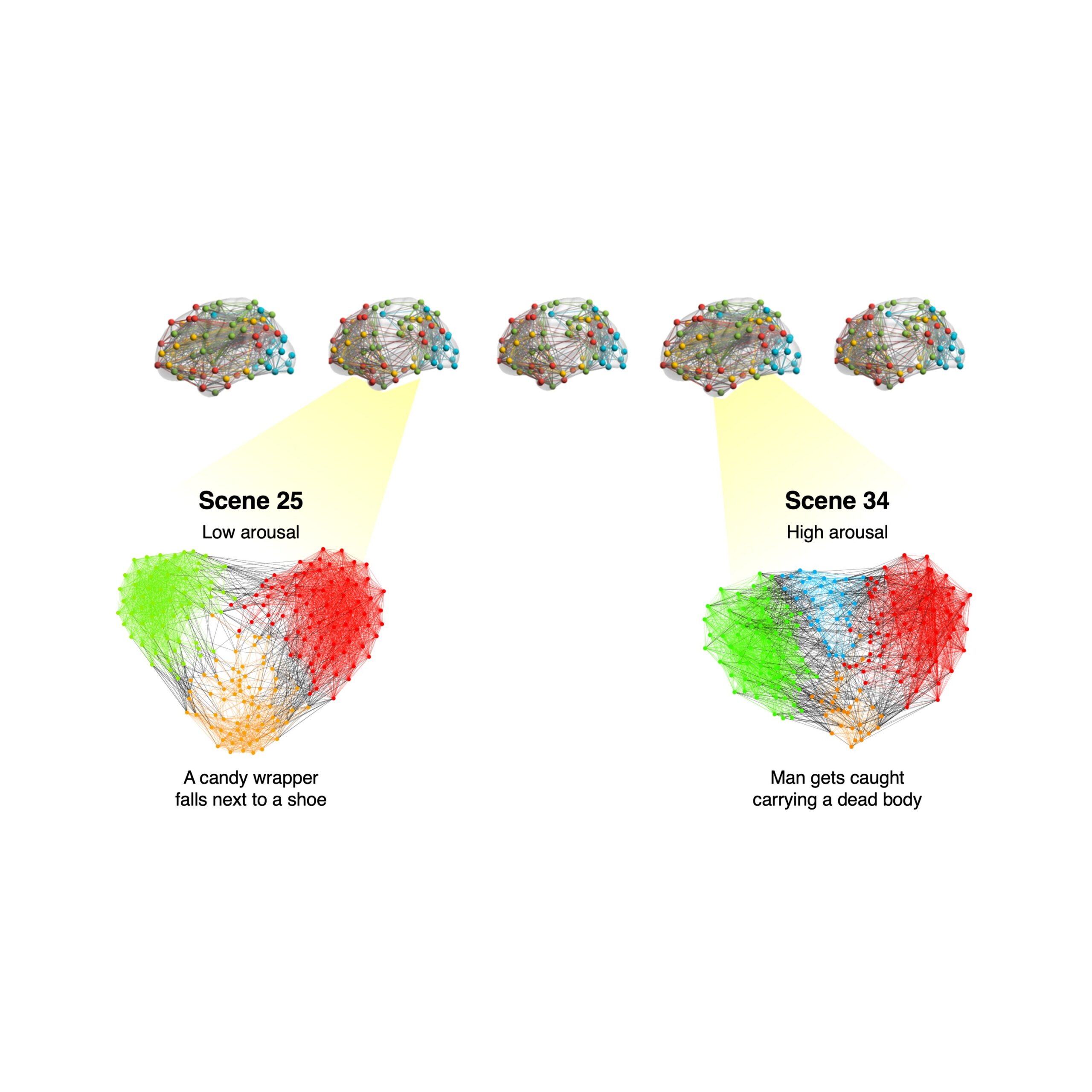

What they found was striking. When people were emotionally aroused, their brains behaved differently. The usual division of labor—different regions working somewhat independently—gave way to a greater harmony. Brain networks began communicating more closely, exchanging information in a way that predicted how well a participant would later remember a scene.

The Orchestra of the Mind

The researchers describe this synchronized activity as an “orchestral” model of memory. In this view, emotions act like a conductor, bringing together different sections of the brain into a unified performance. Rather than relying on a single region—such as the hippocampus, which is classically linked to memory—the entire network of emotional, sensory, and cognitive systems becomes intertwined.

This insight challenges older views of emotional memory. For decades, scientists have known that structures like the amygdala play an important role in emotional processing and memory formation. However, the new findings suggest that emotions don’t simply turn on the amygdala—they connect it to a broader ensemble of regions responsible for perception, attention, and meaning.

It’s this coordination, not isolated activity, that determines how deeply an emotional event imprints itself on the mind. In other words, the strength of memory doesn’t just depend on how strongly a single brain area reacts, but on how well multiple systems communicate and share information in the emotional moment.

A New Understanding of Emotional Memory

Leong and his team’s findings paint a richer picture of how memories are born. Emotional arousal doesn’t merely amplify a snapshot of experience—it transforms the brain into a more integrated and efficient network, weaving together sensory impressions, thoughts, and feelings into a lasting tapestry.

This discovery opens the door to new interpretations of how we form and recall emotional memories. It explains why some memories—such as the moment of first love or a life-changing tragedy—feel multidimensional, filled with texture, sound, and meaning. The brain doesn’t just store these moments; it relives them through the vivid connections forged in emotional arousal.

Moreover, this understanding helps explain why emotional events can sometimes distort memory. When emotions heighten the coordination between brain regions, they also heighten the brain’s storytelling tendencies. This means we might remember emotionally charged moments not exactly as they were, but as we felt them—colored by the significance they held at the time.

The Promise of New Interventions

Beyond advancing theory, this research holds promise for improving mental health. If emotional memories depend on how brain networks communicate, then influencing that communication could help people manage painful or intrusive memories. Leong’s team suggests that future interventions might use neurostimulation techniques, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), to strengthen or weaken specific network connections.

Pharmacological methods might also be explored. Drugs that modulate arousal or neural communication—such as beta blockers, which can reduce the emotional impact of traumatic events—could be used to influence how memories are encoded. These strategies could one day aid people suffering from conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), where emotional memories become overwhelming and persistent.

The researchers are careful to emphasize that these possibilities are still in the future. But the potential is clear: by understanding how emotions shape memory at the level of brain networks, psychology and neuroscience could move toward more precise, targeted ways of helping people reshape their relationships with the past.

Emotion as the Architect of the Self

Memory is not just a record of what has happened—it is the foundation of who we are. Every belief, habit, and hope is built upon the stories our brains choose to preserve. When emotion guides which memories endure, it also shapes our identity. We become, in essence, the sum of what we have felt most deeply.

This realization makes the University of Chicago study even more profound. By revealing how emotional arousal coordinates the brain’s systems, it shows that our most meaningful experiences are not accidents of chemistry—they are carefully orchestrated neural symphonies. Our brains are wired not only to remember, but to feel the world in a way that binds memory to emotion, turning raw experience into the narrative of a life.

The Future of Emotional Neuroscience

The team’s use of artificial intelligence tools—especially natural language processing—marks a new era for neuroscience. By combining computational models with brain imaging, scientists can now study the complex interplay between thought, feeling, and memory with unprecedented depth.

In the future, these tools might help explore how emotions influence autobiographical memory—the deeply personal stories we tell ourselves about our lives. Researchers could map how love, fear, and hope sculpt the brain’s connectivity over time, and how those patterns predict mental health, creativity, and resilience.

As first author Jadyn Park explained, their long-term goal is to directly test how manipulating network integration affects emotional memory. Whether through neurostimulation, therapy, or medication, the ultimate hope is to help people gain control over the memories that shape them—for better or for worse.

Remembering What Matters

The new understanding of emotional memory does more than explain why we remember certain events so vividly—it reveals something essential about being human. Emotion is not just the color of experience; it is the architecture of remembrance. It connects us to joy, to sorrow, to one another. It ensures that the moments that change us most deeply never truly fade.

The next time a memory rises suddenly and sharply—so real it takes your breath away—it may help to remember what science now shows: that such memories endure not by chance, but by design. In the grand orchestra of the brain, emotion plays the conductor’s role, ensuring that the moments which move us most continue to resonate through time.

We remember because we feel. And we feel because, at our deepest level, our minds are built to hold on to what truly matters.

More information: Jadyn S. Park et al, Emotional arousal enhances narrative memories through functional integration of large-scale brain networks, Nature Human Behaviour (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-025-02315-1.