Colorectal cancer has long stood as one of humanity’s most stubborn foes. Behind its clinical name lies a devastating truth—it is one of the leading causes of cancer deaths across the globe. Every year, hundreds of thousands of people face the harsh reality of a diagnosis that carries both fear and uncertainty. In recent years, medicine has made extraordinary strides in harnessing the body’s own defenses to fight back. Immunotherapy, once considered science fiction, now saves lives by awakening the immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. Yet for most patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, this revolution has fallen short. Their immune systems, somehow, remain blind to the tumor’s presence.

A new study, published in Nature Genetics and led by Drs. Eduard Batlle and Alejandro Prados of IRB Barcelona, together with Dr. Holger Heyn from CNAG, has taken a significant step toward understanding why. Their work reveals that colorectal tumors do not merely grow—they build defenses, erecting a sophisticated dual barrier that prevents immune cells from mounting an attack. This invisible fortress, orchestrated by a hormone called TGF-β (Transforming Growth Factor Beta), may hold the key to unlocking new, more effective treatments for patients who currently have few options left.

The Hidden Fortress of Cancer

For years, oncologists have known that tumors are not just clusters of rogue cells multiplying unchecked. They are living ecosystems—complex, dynamic environments where cancer cells manipulate their surroundings to survive. What the new research reveals is how colorectal tumors use TGF-β as their secret weapon.

TGF-β is a natural molecule present in the human body. Under normal circumstances, it plays an important role in healing wounds, regulating inflammation, and keeping cell growth in balance. But in the twisted logic of cancer, what is meant for healing becomes a shield for harm. The study shows that colorectal tumors hijack TGF-β to create a dual defense system that effectively hides them from immune attack.

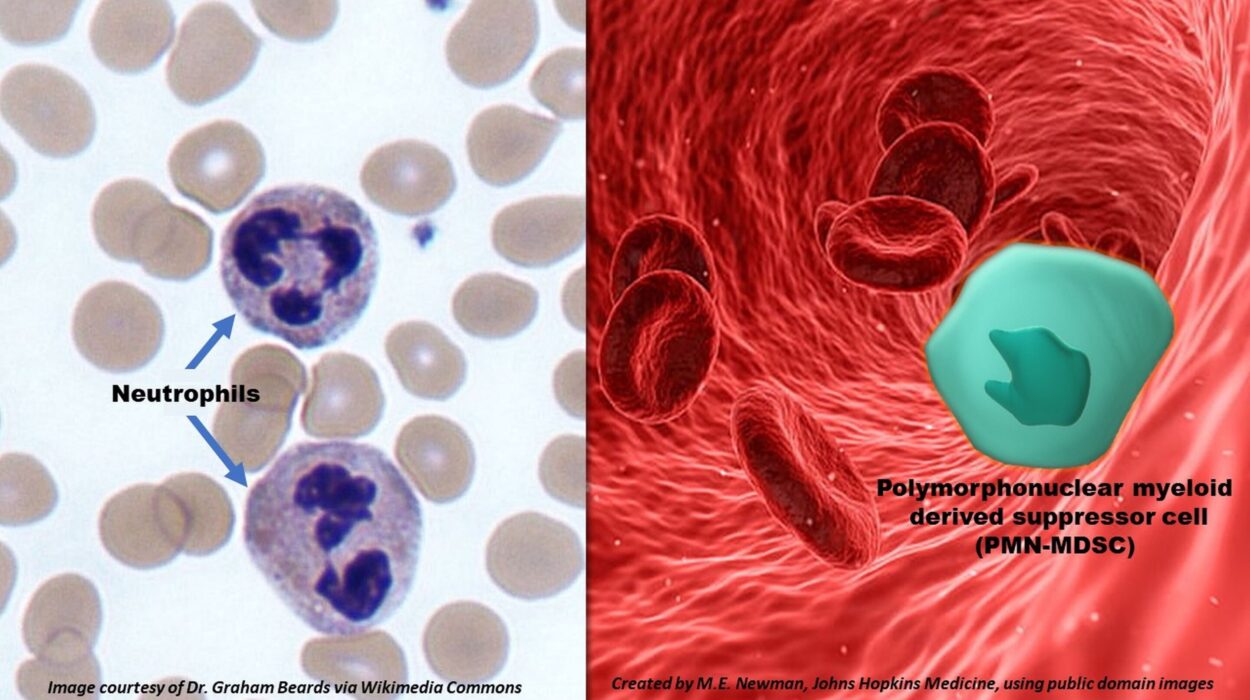

The first line of defense lies in the bloodstream. TGF-β sends a signal that prevents T lymphocytes—white blood cells specialized in hunting and destroying abnormal cells—from reaching the tumor. Even though the immune system may recognize something is wrong, it cannot send enough soldiers to the battlefield.

The second line of defense occurs inside the tumor itself. For the few T cells that manage to slip through, TGF-β changes the surrounding environment. It turns supportive immune cells, known as macrophages, into accomplices. These reprogrammed macrophages begin to produce a protein called osteopontin, which paralyzes the few infiltrating T cells and prevents them from multiplying. The tumor, surrounded by its own chemical fog, becomes nearly invisible to the body’s defenses.

“Our work shows that tumors defend themselves against immunotherapies by manipulating their environment to slow the immune response on two fronts,” says Dr. Eduard Batlle, ICREA research professor and head of the Colorectal Cancer Laboratory at IRB Barcelona. “Understanding this communication language between the tumor and the immune system opens the door to designing strategies that can deactivate these defenses and thus improve the efficacy of immunotherapy.”

Seeing the Enemy Up Close

To uncover these mechanisms, the research team employed one of the most advanced tools in modern biology—single-cell sequencing. This technology allows scientists to study individual cells within a tumor, one by one, revealing a level of detail never before possible.

“By sequencing individual cells within the tumor microenvironment, we have been able to characterize the main players affected by TGF-β,” explains Dr. Holger Heyn, who leads the Single Cell Genomics Group at CNAG. “Applying state-of-the-art technology, we observed how TGF-β blocks immunotherapy efficacy and identified new therapeutic targets to improve colorectal cancer treatments.”

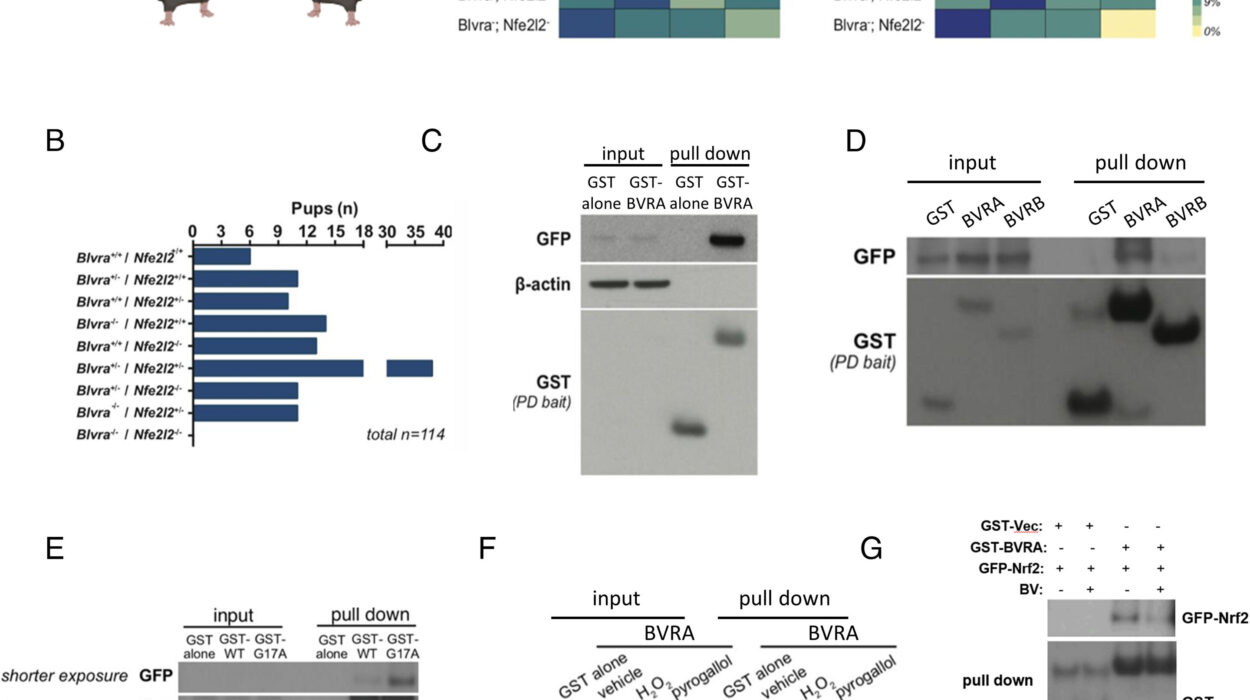

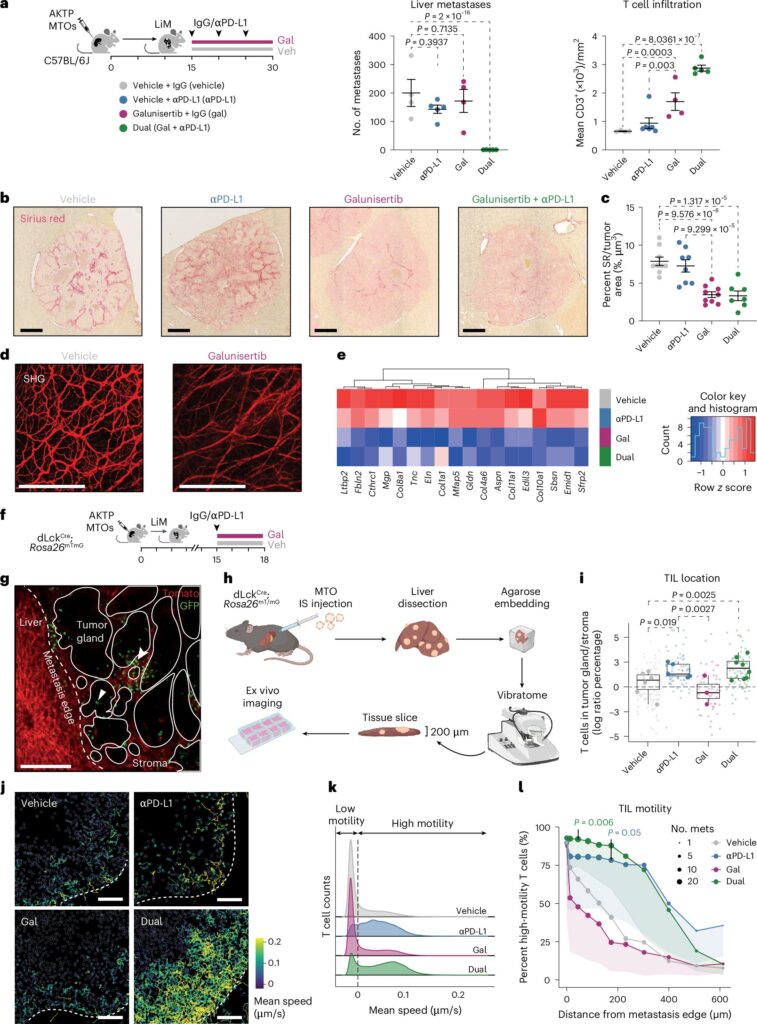

The researchers combined insights from both experimental models of metastasis in mice and tumor samples from patients. What emerged was a clear and intricate picture: TGF-β acts like a molecular conductor, orchestrating a symphony of suppression across the tumor landscape. The result is a finely tuned resistance that keeps immune therapies from doing their work.

Breaking the Barriers

If the tumor’s defenses could be dismantled, could the immune system finally prevail? The team tested that question. By blocking TGF-β’s activity in their experimental models, they found something remarkable—the immune cells were suddenly able to flood into the tumor and attack it with renewed strength.

“In our experimental models, when we blocked the action of TGF-β, the immune cells were able to massively enter the tumor and regain their capacity to attack,” says Dr. Ana Henriques, the paper’s first author. “Furthermore, when combining this blockade with immunotherapy, we observed very potent anti-tumor responses.”

This finding is powerful because it suggests that TGF-β is not merely one of many obstacles—it may be the master switch controlling immune resistance in colorectal cancer. When this switch is turned off, the immune system wakes up.

The Road to Safer Treatments

While there are already drugs in development that can inhibit TGF-β, their use in patients has been limited due to significant side effects. TGF-β plays roles throughout the body, not just in tumors, so shutting it down completely can cause serious complications. The challenge now is to find smarter, more selective ways to interfere with its harmful actions while preserving its normal functions.

This study offers new hope in that regard. Instead of targeting TGF-β itself, researchers suggest focusing on the molecules it activates, such as osteopontin. By blocking these downstream signals, doctors may be able to neutralize the tumor’s defenses without causing widespread harm.

“In any case, these alternatives will need to be evaluated in clinical trials, and always in combination with immunotherapy,” notes Dr. Batlle. “Understanding this circuit allows us to search for safer and more selective solutions. The ultimate goal for immunotherapies, which today only work in a small group of patients, is to be able to also benefit the majority of those with metastatic colorectal cancer,” adds Dr. Prados, formerly at IRB Barcelona and now a researcher at the University of Granada.

Hope on the Horizon

Every discovery in cancer biology is a step on a long and winding road—a path paved with persistence, creativity, and compassion. The significance of this new research lies not only in the science itself but in what it represents: a renewed hope for patients who have exhausted their options.

The concept that cancer can be taught to “unhide” itself from the immune system could revolutionize how we approach not only colorectal cancer but other types as well. Many tumors employ similar strategies to evade immune detection, and TGF-β’s dual barrier might be a universal feature of cancer’s defensive playbook. By decoding it, scientists could unlock new therapies capable of transforming grim prognoses into survivable conditions.

The Human Story Behind the Science

Behind every data point in the study lies the story of a patient—someone sitting in a clinic, waiting for a treatment that could give them more time, more life. Scientific breakthroughs often appear cold and technical on paper, but their purpose is deeply human.

The researchers behind this work are driven by more than curiosity. They are driven by empathy, by the quiet urgency of knowing that understanding one molecule’s behavior could change thousands of lives. In their laboratories, under the hum of microscopes and sequencing machines, they are rewriting the story of how we fight cancer—not with brute force, but with precision, patience, and a deep respect for the elegance of biology.

Toward a New Era of Cancer Treatment

Cancer research today is entering a new age—one where the focus shifts from destroying tumors at all costs to understanding their intelligence. Tumors are not passive lumps of cells; they are evolving entities that learn to adapt, resist, and survive. To outsmart them, medicine must learn to speak their language.

The discovery of TGF-β’s dual barrier offers just that—a glimpse into cancer’s internal dialogue. By learning how it communicates with the immune system, we can begin to turn its own strategies against it. Immunotherapy, once limited to a lucky few, could become a weapon for many more.

In the grand battle between life and disease, every insight matters. This study, meticulous and profound, reminds us that even in the darkest complexity, knowledge can bring light.

A Future Within Reach

As science continues to unravel the mysteries of the immune system and cancer’s hidden tactics, the future of treatment becomes not just a matter of medicine but of imagination. Perhaps one day, thanks to discoveries like this, immunotherapy will no longer be a gamble but a guaranteed lifeline—a universal key that unlocks the body’s full healing potential.

For now, the work of Drs. Batlle, Prados, Heyn, and their teams offers both clarity and courage. It tells us that progress is possible, that the walls cancer builds can indeed be breached, and that with enough persistence, understanding, and compassion, even the most insidious disease can be outwitted.

Colorectal cancer remains a formidable adversary. But science, armed with insight and humanity, is learning how to speak its language—and slowly, surely, to silence it.

More information: Ana Henriques et al, TGF-β builds a dual immune barrier in colorectal cancer by impairing T cell recruitment and instructing immunosuppressive SPP1+ macrophages, Nature Genetics (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41588-025-02380-2.