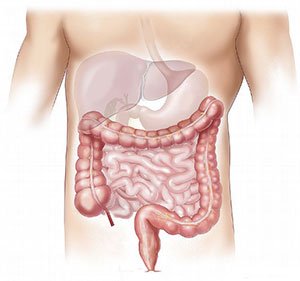

For decades, the story of depression and anxiety has centered on the brain—a chemical imbalance, often of serotonin, long seen as the culprit behind low moods, despair, and nervous unease. Medications like Prozac and Zoloft, known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have become pharmaceutical cornerstones of modern psychiatry, fine-tuned to increase serotonin levels in the brain. But what if the brain isn’t the whole story? What if, buried deep in the coils of the gastrointestinal tract, lies a more important key to emotional balance?

A groundbreaking new study published in Gastroenterology has turned that question into a provocative possibility. Researchers led by neuroscientist Mark Ansorge of Columbia University and pediatric gastroenterologist Kara Margolis of New York University have uncovered compelling evidence that the gut’s own serotonin—not just what circulates in the brain—may be a powerful modulator of mood. Their findings could pave the way for a safer class of antidepressants, particularly for pregnant women and children, who are more vulnerable to the side effects of traditional treatments.

A Dual Puzzle: Depression and Digestion

The backdrop to this study is a longstanding paradox in medicine. SSRIs are widely prescribed for depression and anxiety, yet they come with an array of side effects—many of them centered in the gut. Nausea, diarrhea, constipation, and appetite changes are common complaints, especially in the early days of treatment. And for pregnant individuals, SSRIs raise deeper concerns: these drugs cross the placenta, potentially influencing the development of the fetal brain and gastrointestinal system.

Despite their widespread use, the precise location in the body where SSRIs exert their antidepressant effects remains elusive. The assumption has been that serotonin acts primarily within the brain. But this perspective neglects a remarkable biological fact: around 90–95% of the body’s serotonin is not in the brain at all. It’s produced in the gut.

This disconnect set the stage for Ansorge and Margolis’s ambitious investigation. Could it be that the gut, long viewed as peripheral to psychiatry, is actually commanding a key role in shaping emotional well-being?

Engineering Mood from the Inside Out

To explore this, the researchers turned to mice—specifically, mice genetically engineered to help them pinpoint the source of serotonin’s power. They focused on a protein called SERT (serotonin transporter), which clears serotonin from the spaces between cells. By removing SERT only in the gut lining, they could precisely boost serotonin levels in the intestine, without altering levels in the brain.

Two groups of mice were created. In one, SERT was deleted from birth, allowing the animals to grow up with persistently elevated serotonin in the gut. In the second, the deletion occurred only in adulthood, mimicking what might happen in an adult human taking a gut-specific drug.

The results were striking. In behavioral tests designed to measure anxiety and depression—such as willingness to explore new spaces, eat in unfamiliar environments, or struggle during the tail suspension test—both groups of mice showed significantly reduced anxiety- and depression-like behaviors. They were more curious, more resilient, and more active than their normal counterparts.

In short: boosting gut serotonin improved mood.

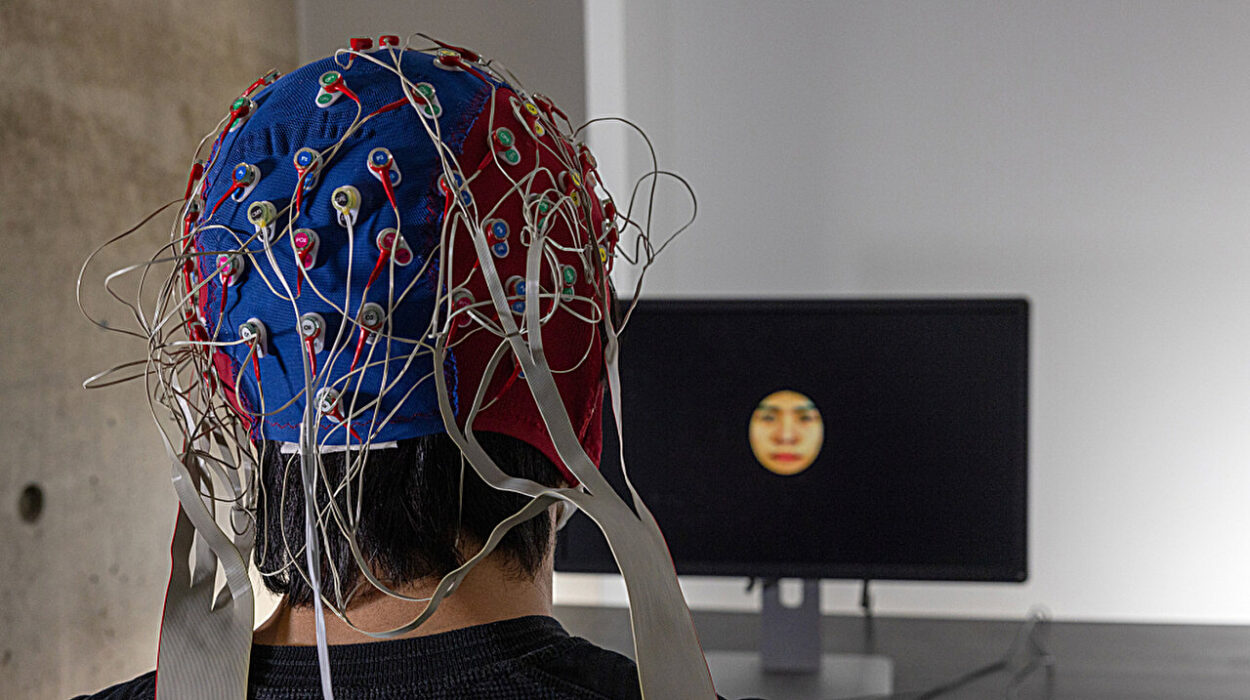

The Vagus Nerve: The Gut’s Hotline to the Brain

But how did these changes occur if the brain’s serotonin levels weren’t altered?

To answer that, the team examined the vagus nerve—a long, wandering nerve that links the brain to multiple organs, including the digestive tract. It serves as a high-speed communication line between gut and mind. When the researchers surgically severed the vagus nerve in mice with elevated gut serotonin, the mood benefits disappeared.

This revealed a crucial insight: serotonin in the gut appears to affect the brain not by crossing the blood-brain barrier, but by sending signals through the vagus nerve. It’s a subtle but profound rethinking of how mood regulation may work. The gut is not just responding to brain states—it’s initiating them.

What Happens When Gut Serotonin Is Too Low?

To ensure this wasn’t a one-way street, the researchers also ran reverse experiments. They used genetically modified mice that couldn’t produce serotonin in their intestines and administered a drug that blocks serotonin synthesis locally in the gut. These mice, deprived of their gut-derived serotonin, became more anxious and exhibited behaviors associated with depression.

The implication was clear: the absence of serotonin in the gut—not the brain—was enough to produce mood changes. This bolstered the idea that the gut’s serotonin system is not just a passive player, but a critical regulator of emotional health.

An Unexpected Clue from Human Infants

While mouse models can offer powerful biological insights, real-world implications require validation in people. For that, the team turned to human data—specifically, a cohort of over 400 mother-child pairs enrolled in a Canadian birth study.

These families were categorized based on whether the mothers had taken SSRIs during pregnancy, experienced untreated depression, or had no mental health concerns. When researchers examined the infants one year after birth, a striking pattern emerged. Infants exposed to SSRIs in utero were three times more likely to develop functional constipation compared to those whose mothers did not take the medication.

At one year old, 63% of SSRI-exposed children were constipated, compared to only 31% of their unexposed peers. The result was more than a digestive quirk. Functional constipation in infants is increasingly understood as a gut-brain disorder, one with roots in nervous system signaling and development.

This human data echoed earlier animal studies showing that prenatal exposure to SSRIs could disrupt both brain and gut development. The findings added weight to the argument that serotonin modulation in early life—especially when driven by systemic drugs—has wide-ranging and sometimes unintended consequences.

Redefining Antidepressants for the Gut-Brain Era

If serotonin in the gut can shape mood and behavior via the vagus nerve, and if targeting this pathway avoids the cognitive and developmental side effects of traditional SSRIs, then the future of depression treatment could be about to change.

Crucially, the study showed that gut-targeted manipulation of serotonin did not impair cognition, learning, or memory in mice. Nor did it severely disrupt gut motility. These are common drawbacks of SSRIs, which can cause both mental fog and digestive dysfunction. The localized nature of gut serotonin interventions appears to sidestep these problems.

“We think this approach could be especially valuable during pregnancy,” said Ansorge. “Our data suggest we may be able to treat a mother’s depression or anxiety effectively without exposing the fetus to systemic drugs.”

Margolis, the co-lead, emphasized that the findings are not a call to abandon current treatments. “This is not clinical advice. No one should stop taking their prescribed medication without medical supervision,” she said. “But it is a powerful reminder that more research is needed into how antidepressants affect the gut, especially during early development.”

The Rise of Gut-Centric Mental Health Therapies

The idea that the gut plays a major role in mood is part of a larger scientific revolution—one that’s been gathering steam over the last decade. The “gut-brain axis” has become a central focus of neuroscience, psychiatry, and gastroenterology. Microbes in the gut have been shown to influence stress responses, immune activity, and even neurotransmitter production. Now, this latest research brings serotonin into sharper view as a mood-shaping signal that starts not in the brain, but in the belly.

The team is already working on next-generation antidepressants designed to remain in the gut, avoiding the bloodstream altogether. These could be taken orally, perhaps in a time-released capsule or a microbiome-based formulation, and offer mood improvement without systemic exposure.

Such treatments may also benefit individuals who cannot tolerate SSRIs due to side effects, or those with complex medical conditions where standard antidepressants are contraindicated.

Caution, Curiosity, and Hope

While the excitement is justified, experts are clear: this is early-stage science. Much remains unknown about how gut serotonin operates in humans, how safe localized serotonin treatments would be, and what long-term impacts might emerge. Clinical trials are needed to test gut-targeted antidepressants in real patients with depression and anxiety.

Still, the potential is enormous. A treatment that improves mood, avoids the brain’s delicate architecture, and reduces risk during pregnancy could reshape the landscape of mental health care.

In the words of pediatrician and study co-author Larissa Takser: “This opens new doors. Serotonin is not just a brain chemical—it’s a developmental signal. And now we see how that signal might begin in the gut, even before birth.”

The Gut as Therapist

For too long, the gut has been seen as a secondary organ in mental health—a place where medications cause side effects, not solutions. But this research turns that assumption upside down. The gut may not only be a silent partner in emotional regulation—it may be a master conductor.

If future studies confirm the findings, we could soon see a new class of antidepressants—gut-selective, pregnancy-safe, and side-effect-light—emerging from this work. And with them, a fundamental shift in how we treat the most pervasive mental health conditions of our time.

In that vision, the pathway to peace of mind may be less about what’s in your head—and more about what’s happening in your gut.