Depression is far more than a passing sadness—it is one of the most common and challenging psychiatric disorders in the world, affecting nearly 3.8% of the global population. For those living with its most severe form, major depression (MD), daily life can become overwhelming. Work, relationships, hobbies, even the simplest routines like eating or sleeping can feel impossible to manage.

Traditionally, depression has been understood as the result of a complex interaction between genetics and environmental influences such as stress, trauma, or lifestyle. But how exactly our genetic blueprint interacts with our brains to shape vulnerability has long remained a mystery.

Now, an ambitious new study brings us closer to answering this question by uncovering how genetic risk for depression is physically reflected in the structure of the brain.

Tracing the Genetic Blueprint of Depression

Our genes do not dictate destiny, but they do influence our likelihood of developing certain conditions. To measure this influence, researchers use something called a polygenic risk score (PRS). Unlike a single genetic mutation that directly causes a disease, PRS takes into account the combined effect of thousands of genetic variations, each contributing a tiny amount to overall risk.

In the case of depression, PRS gives scientists a way to estimate an individual’s genetic vulnerability—like a probability score for developing the disorder at some point in life. Yet, while this score can tell us something about risk, it doesn’t explain what happens in the brain when that risk is high. That’s the question researchers set out to explore.

An International Effort to Map the Depressed Brain

A team of scientists from the University of Edinburgh, the University of Melbourne, Vrije University Amsterdam, and several other institutions joined forces in one of the largest efforts of its kind. They analyzed genetic and brain imaging data from nearly 51,000 people, collected through 11 international studies under the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group.

To ensure accuracy, the team developed highly consistent protocols for both genetic testing and neuroimaging. This massive collaboration allowed them to conduct the first true “mega-analysis” of how genetic risk for depression might leave its imprint on the brain’s physical structure.

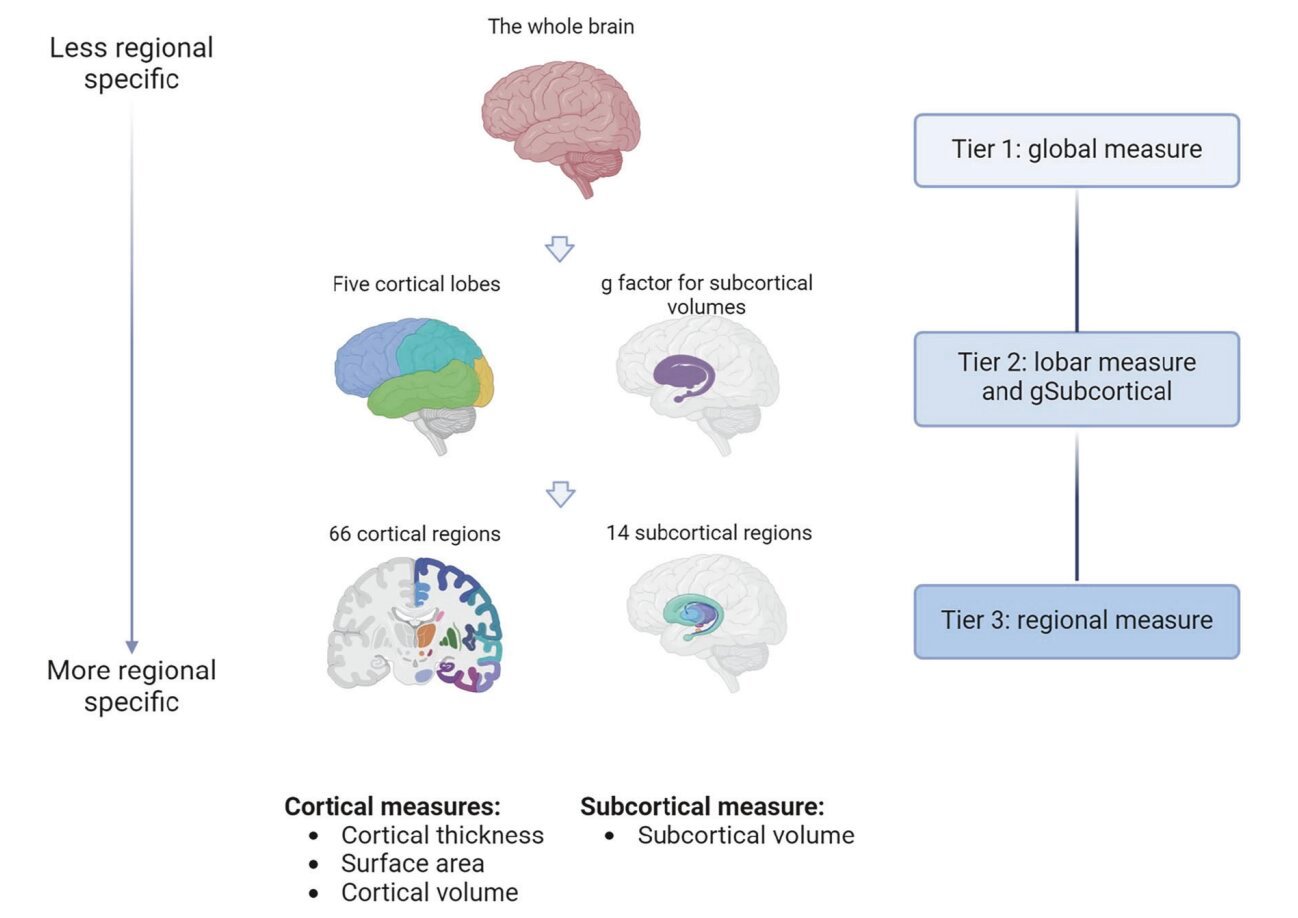

The Brain Regions Most Affected

The results revealed something striking: people with higher PRS for depression tended to have smaller brain volumes and reduced cortical surface areas in key regions.

Most notably, these differences appeared in areas deeply tied to mood regulation, memory, and decision-making:

- Frontal lobe (left medial orbitofrontal gyrus): A region critical for emotional control, reward processing, and decision-making.

- Hippocampus: Essential for memory and stress regulation, often found to be smaller in individuals with depression.

- Thalamus: A sensory and emotional relay center, linking body signals with conscious perception.

- Pallidum: Part of the brain’s reward system, connected with motivation and pleasure.

In simple terms, the very architecture of the brain seems to reflect genetic vulnerability to depression. Those at higher genetic risk had smaller and thinner structures in the regions most responsible for how we feel, think, and respond to the world.

Age and Vulnerability

Interestingly, the patterns were found in both younger participants (under 25) and adults. While the differences were less pronounced in younger individuals, the same structural changes were present. This suggests that genetic risk factors may begin influencing brain development early in life—possibly even before symptoms of depression appear.

This discovery raises profound questions: could early brain imaging one day help identify those most at risk? Could preventive therapies be tailored before depression fully takes hold?

A Closer Look at the Hippocampus

One of the most important findings was the link between genetic risk and the hippocampus. Through a technique known as Mendelian randomization, researchers found evidence that smaller hippocampal volume may not just be associated with depression but could potentially contribute to causing it.

This is significant because the hippocampus is highly sensitive to stress and plays a crucial role in regulating emotions. If genetic risk makes this structure smaller or more vulnerable, it may help explain why some individuals are more likely to develop depression when exposed to stressful life events.

The Promise of Personalized Medicine

While this study does not mean that genes alone determine mental health, it does open new pathways toward personalized medicine. By combining genetic risk scores with brain imaging, doctors might one day be able to predict who is most vulnerable to depression long before symptoms appear.

More importantly, these insights could guide targeted therapies. For example, treatments that specifically strengthen hippocampal function or enhance frontal lobe activity could be developed for those with higher genetic risk.

In the long run, this might mean shifting from a “one-size-fits-all” approach to mental health care toward interventions that are tailored to each individual’s biological profile.

A Window Into the Future of Mental Health

Depression remains one of the world’s greatest health challenges, both in its prevalence and in the suffering it causes. Yet, studies like this remind us that progress is possible. By uncovering the hidden connections between genes, brain structure, and mental health, researchers are building a roadmap toward earlier diagnosis, more effective treatments, and—most importantly—hope for millions of people worldwide.

Science still has a long way to go, but the message is clear: depression is not just “in the mind.” It is written into the biology of the brain, shaped by genetics, and expressed in ways we are only beginning to understand.

And with every new discovery, we move closer to a future where no one has to face depression without answers, without help, and without hope.

More information: Xueyi Shen et al, Association between polygenic risk for Major Depression and brain structure in a mega-analysis of 50,975 participants across 11 studies, Molecular Psychiatry (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-025-03136-4