Across vast fields of green, farmers rely on plant protection products—fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides—to keep crops healthy and productive. These chemicals are the silent guardians of modern agriculture, ensuring that pests, diseases, and weeds do not devastate the world’s food supply. Yet, like many tools of human progress, they come with a hidden cost.

Beneath the surface of our thriving farmlands, something quieter is happening—something we cannot easily see. These same chemicals, designed to target crop-destroying organisms, are seeping into the lives of creatures they were never meant to touch. From the fluttering of a bee’s wings to the darting of a fish in a stream, life at the edges of the field is changing in subtle, troubling ways.

A team of scientists at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) in Germany has been studying this delicate intersection between protection and harm. Their findings paint a complex, emotionally charged picture of how human attempts to safeguard crops may be reshaping the natural behaviors of animals that are vital to ecosystems.

The Unintended Victims of Progress

Modern agriculture operates under strict regulations that aim to ensure the safe use of plant protection products. Yet, no barrier is perfect. The same rain that nourishes crops also washes traces of these chemicals into nearby rivers and ponds. The same breeze that carries the scent of blossoms also carries invisible particles toward the buzzing pollinators that visit them.

“Wild bees and other pollinators can come into contact with quite high concentrations shortly after spraying,” explains UFZ biologist Professor Martin von Bergen, one of the study’s principal investigators. “But animals in aquatic habitats are also at risk. Rainfall gradually washes plant protection products into the surrounding waters. They don’t simply remain and only affect the area where they are applied.”

The realization is unsettling: our efforts to protect food security may be rippling outward, affecting the intricate web of life that supports the planet’s balance.

Tiny Creatures, Tremendous Clues

To explore this hidden world of chemical influence, the UFZ researchers chose two small yet powerful models of life—the honeybee (Apis mellifera) and the zebrafish (Danio rerio). These species are more than just convenient research subjects. They represent two different worlds—the terrestrial and the aquatic—both essential for sustaining life as we know it.

Honeybees are not just pollinators; they are the quiet workers that enable nearly one-third of global food crops to reproduce. Zebrafish, on the other hand, serve as a window into aquatic health. Their transparent embryos and predictable development make them ideal for studying the effects of environmental stressors on vertebrates.

The team’s approach was as precise as it was humane. Instead of exposing animals to high, unrealistic doses, the researchers simulated the kinds of concentrations actually found in nature—those lingering traces of chemicals that persist long after the farmer has packed away the sprayer.

When Bees Forget Their Dance

The results were both fascinating and worrying. In the honeybees, exposure to common insecticides caused a noticeable reduction in foraging activity. Bees became less efficient, slower, and less coordinated in their search for nectar. Even their ability to process nectar—an intricate behavior vital for turning raw floral syrup into honey—was altered.

When treated with fungicides and herbicides, bees displayed reduced brood care behaviors. They tended to larvae less attentively, and their colonies’ overall cohesion weakened. What might seem like minor changes in behavior can, over time, have enormous consequences. If bees forage less or care for their young inadequately, entire colonies can falter.

Such disruptions do not just affect bees—they ripple across ecosystems. Pollination is not merely a service; it is the heartbeat of biodiversity. Fewer pollinators mean fewer flowers, fewer fruits, and fewer seeds. The loss travels up the food chain, touching birds, mammals, and ultimately humans.

“Such behavioral changes, triggered by environmentally relevant concentrations of plant protection products, can impair the performance and maintenance of colonies and ultimately also their pollination services,” says Cassandra Uthoff, the UFZ doctoral student who led the study. Her tone carries both scientific precision and quiet alarm.

The Fish That Forgot How to Swim Right

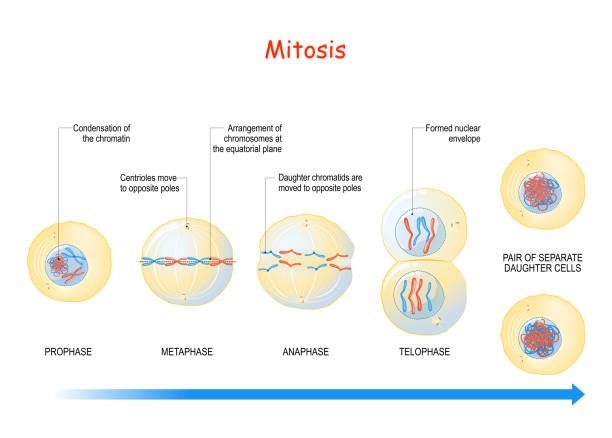

The researchers didn’t stop with pollinators. Beneath the shimmering surface of freshwater streams, they turned their attention to zebrafish embryos. These tiny, transparent beings reveal the effects of chemicals with uncanny clarity.

Using a behavior-based screening method, the team examined how exposure to insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides affected zebrafish learning, movement, and memory. The results again told a story of disturbance. Even at low concentrations, the fish embryos displayed measurable behavioral changes.

When exposed to mixtures of chemicals—combinations actually found in small German streams—the effects became even more complex. At low concentrations, fish behaved as if only one type of chemical (the herbicide) was influencing them. But as concentrations increased, this pattern flipped: the behavior shifted to resemble that seen with exposure to fungicides instead.

These subtle changes may seem abstract in the controlled setting of a lab, but in the wild, behavior is survival. A fish that swims slower, forgets learned responses, or fails to evade predators stands little chance in nature’s unforgiving theater.

“The work demonstrates that mixtures of co-occurring plant protection products have the capacity to alter organismal behavior at environmentally relevant concentrations,” notes Professor Tamara Tal, UFZ ecotoxicologist and co-head of the study. Her words echo a larger truth: ecosystems do not encounter single chemicals in isolation—they experience complex cocktails of them, all interacting in unpredictable ways.

The Domino Effect on Ecosystems

The implications of these findings reach far beyond bees and fish. Behavior is one of the most fundamental aspects of life. It governs feeding, reproduction, migration, and social interaction. When behavior changes, even slightly, the effects can cascade through entire ecosystems.

A pollinator that forgets to visit flowers reduces plant reproduction. A fish that fails to flee a predator affects population dynamics. A decline in one species can ripple through food webs, destabilizing balances that took millions of years to evolve.

The UFZ study suggests that the real impact of plant protection products may be far greater—and far more subtle—than previously assumed. While traditional risk assessments focus on lethal effects, they may overlook these delicate behavioral shifts that gradually erode the resilience of ecosystems.

The Case for a New Kind of Risk Assessment

Current regulations do include behavioral testing for certain chemicals, but these tests are often too simplistic and not always mandatory. They tend to measure direct toxicity—whether a chemical kills an organism—rather than how it influences complex patterns like navigation, learning, or cooperation.

The UFZ researchers argue that it’s time for a change. “Although animal behavior tests following exposure to low concentrations of chemicals are already included in the risk assessment of chemicals in some cases, these tests are not complex enough and are typically not mandatory,” Uthoff explains.

By integrating more sophisticated behavioral analyses into risk assessments, scientists could detect early warning signs of harm long before populations decline or ecosystems collapse. It’s a proactive approach—one that recognizes the living world not as a collection of isolated parts, but as an intricate network of interdependent lives.

Beyond Data: A Moral Wake-Up Call

Behind every chart, graph, and data point in this study lies a moral question: how much unintended harm are we willing to accept in the name of human progress? Farmers rely on plant protection products to sustain global food production, and indeed, these tools are indispensable for preventing famine and economic loss. Yet, as the UFZ research reveals, the cost is not paid in immediate human suffering—it is paid quietly, by bees that can no longer find their way home, by fish that lose their instinctive grace, by ecosystems that slowly unravel.

This realization should not lead to despair but to responsibility. The answer is not to abandon plant protection products altogether, but to make them safer, smarter, and more sustainable. It means understanding the full ecological consequences of their use—not just the visible ones.

The Path Toward Balance

There is hope in the work of scientists like those at UFZ. Their research bridges the gap between agricultural necessity and environmental stewardship. By exposing how small doses can cause big changes, they invite us to imagine a future where food security and biodiversity are not opposing goals, but complementary ones.

Incorporating behavioral studies into risk assessments could reshape how we evaluate chemical safety. Instead of focusing solely on survival, we could ask a more profound question: are the animals still living well? Are they thriving, reproducing, navigating, learning, and behaving naturally? These are the measures of true ecological health.

More information: Cassandra Uthoff et al, Cross-taxa sublethal impacts of plant protection products on honeybee in-hive and zebrafish swimming behaviours at environmentally relevant concentrations, Environment International (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2025.109750