For decades, evolutionary biologists held a quiet confidence in a simple, elegant idea. If a genetic mutation managed to spread through an entire population, it was probably nothing special—neither harmful nor helpful, just neutral enough to drift into permanence. This assumption, known as the Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution, shaped the way scientists understood the genetic churn beneath the surface of life.

But inside a lab at the University of Michigan, that calm certainty has begun to unravel. A team led by evolutionary biologist Jianzhi Zhang has uncovered something far more turbulent, far more dramatic, and far more alive than anyone expected.

What they found wasn’t a peaceful march of neutral mutations. It was a restless chase—life struggling to keep up with environments that never stop changing.

A Theory Meets Its Breaking Point

The Neutral Theory was built on comforting logic: harmful mutations disappear quickly, helpful ones are rare, and anything that becomes fixed across an entire population is probably neither good nor bad. Zhang explains this long-standing assumption with steady clarity, saying the theory “posits that most genetic mutations that are fixed are neutral.”

But when his team set out to test that idea, the data told a very different story.

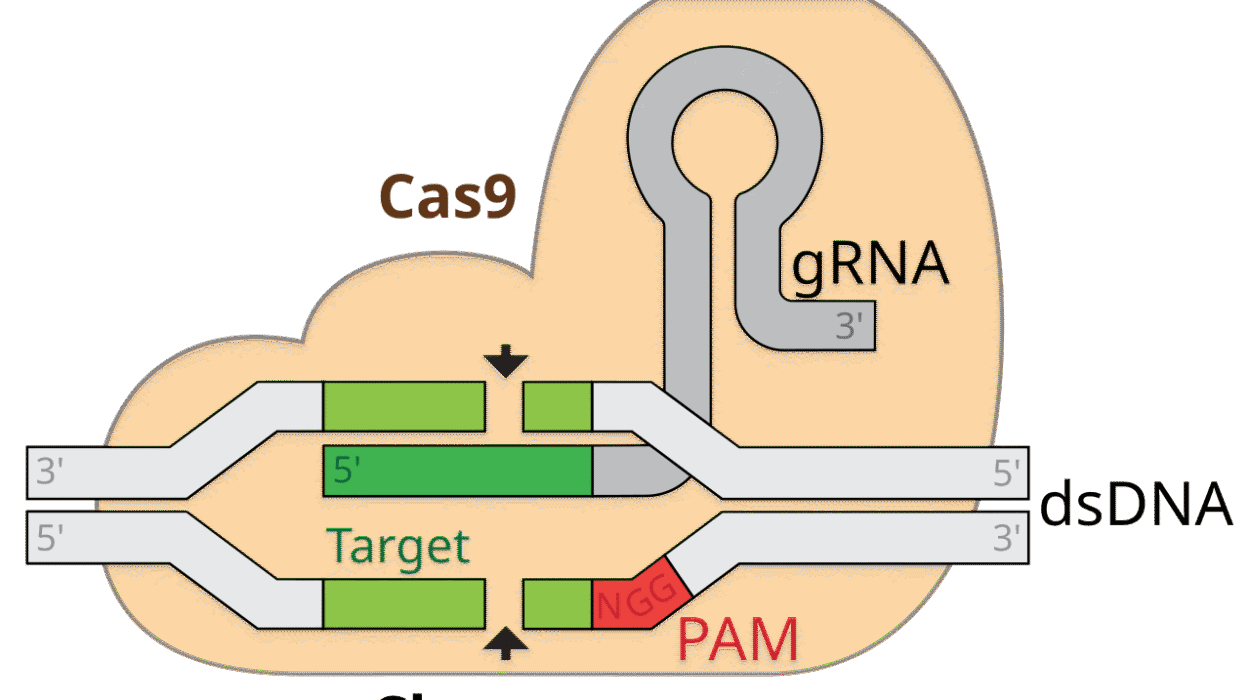

Using deep mutational scanning—an approach that generates and monitors enormous sets of mutations in organisms like yeast and E. coli—Zhang and his colleagues measured the effects of thousands of changes in specific genes. They followed the mutated organisms over generations, comparing their growth to the wild type, the form most common in nature.

What emerged was astonishing. Beneficial mutations were not rare at all. In fact, more than 1% of mutations helped organisms grow better. That rate is “orders of magnitude greater than what the Neutral Theory allows,” Zhang’s team concluded.

If that many beneficial mutations exist, then almost all fixed mutations should be helpful too. But real populations don’t evolve that fast. Something was missing, something big.

The researchers realized they had made an assumption the natural world doesn’t honor. They had treated the environment as steady.

Nature, of course, is anything but steady.

The World Is Changing Faster Than Genes Can Keep Up

To explore how shifting conditions might undermine the rise of beneficial mutations, Zhang’s team designed a simple but revealing experiment. They evolved two groups of yeast for 800 generations. One group lived its entire life in a single, constant environment. The other lived in a world that changed every 80 generations, moving through ten different growth media one after another.

What happened inside those flasks told the story.

In the constant environment, beneficial mutations accumulated frequently, just as classical theory would predict. But in the changing environment, those promising mutations almost never became fixed. The yeast might begin to adapt to one condition, only to find themselves swept into another before that adaptation could spread through the population.

“This is where the inconsistency comes from,” Zhang explained. “While we observe a lot of beneficial mutations in a given environment, those beneficial mutations do not have a chance to be fixed because as their frequency increases to a certain level, the environment changes.”

A mutation that is helpful on Monday may be harmful by Friday.

“Those beneficial mutations in the old environment might become deleterious in the new environment,” he said.

The result is an evolutionary paradox. Beneficial changes happen frequently, yet populations don’t speed ahead toward perfection. They are always adjusting, always partially mismatched, always chasing a world that refuses to stay in one place.

A New Vision of Evolution Taking Shape

To make sense of this restless picture, Zhang and his team developed a new framework: Adaptive Tracking with Antagonistic Pleiotropy. In plain language, it proposes that populations are constantly trying to track their shifting environments, but each helpful mutation comes with costs somewhere else. When the world changes quickly, yesterday’s advantage becomes today’s burden.

“We’re saying that the outcome was neutral, but the process was not neutral,” Zhang explained. He sees this principle extending far beyond the yeast in the lab.

“Our model suggests that natural populations are not truly adapted to their environments because environments change very quickly, and populations are always chasing the environment.”

In one of the study’s most sobering reflections, he suggests this applies to humans as well.

“Our environment has changed so much, and our genes may not be the best for today’s environment because we went through a lot of other different environments,” Zhang said. “Some mutations may be beneficial in our old environments, but are mismatched to today.”

The idea that no species may ever achieve full adaptation reshapes the way we think about evolution itself. According to Zhang, “we’re probably never going to see any population that is fully adapted to its environment, because a full adaptation would take longer than almost any natural environment can remain constant.”

Evolution, in this view, is not a march toward perfection. It is a constant pursuit, a race without a finish line.

How Scientists Reached This Moment

The roots of this discovery stretch back to the 1960s, when scientists first gained the ability to sequence proteins and later genes. This shift encouraged a move away from studying evolution mainly through physical forms and toward its molecular machinery. The Neutral Theory was born in that moment, shaped by the data of its time.

But today’s tools go deeper. Zhang’s team used large datasets—some from his lab, some from others—to track the effects of mutations with unprecedented precision. By comparing whole libraries of altered genes against the wild type and measuring their growth over many generations, they could map how each tiny change influenced an organism’s success.

Their findings were striking, but not without limitations. As Zhang notes, yeast and E. coli make ideal subjects because their mutations and growth rates are easy to track. Whether the same patterns hold for multicellular organisms, including humans, remains an open question. The team hopes future deep mutational scans will help them find out.

They are already planning their next study, aimed at unraveling why full adaptation to even a constant environment seems to take so long.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research reshapes the story of evolution, replacing the calm drift of neutral mutations with a picture of relentless pursuit. It suggests that life is not quietly accumulating random changes but is actively, constantly struggling to keep up with an unpredictable world. It reframes adaptation not as a final goal but as a perpetual, dynamic process.

More profoundly, it forces us to rethink how well any species—including humans—is matched to its surroundings. If environments shift faster than genes can follow, no organism stands at the summit of evolution. Every species is in motion, caught between the past that shaped its genome and a future it must chase but can never fully reach.

In Zhang’s words, “the population may be very poorly adapted or it may be relatively well adapted,” depending on when the last environmental shift occurred. But full perfection, he suggests, is out of reach.

The discovery doesn’t make evolution weaker. It makes it more alive—messy, reactive, and endlessly responsive to a world in constant flux.

More information: Adaptive tracking with antagonistic pleiotropy results in seemingly neutral molecular evolution, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-025-02887-1.