It lay there silently for millennia, buried beneath layers of dust, pottery fragments, and ancient bones—a strange, ivory-colored relic in the heart of southern Spain. It was not shaped like a tool or carved like an idol, but it caught the attention of archaeologists the moment it was unearthed in 2018 at a site known locally as the Nueva Biblioteca, or “New Library.” The name was oddly fitting. This discovery, after all, was a kind of book—a fossilized chapter of a story long forgotten, waiting to be read.

The object was a tooth. But not just any tooth.

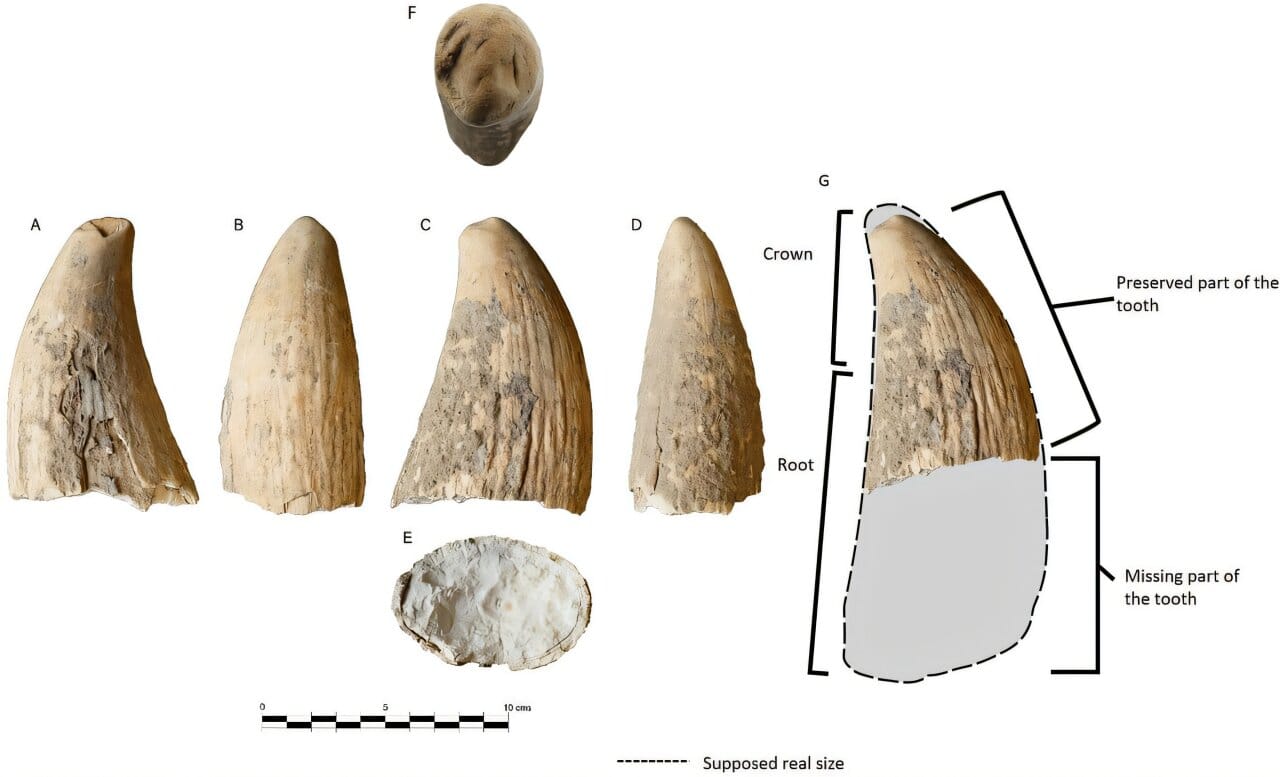

At 13.2 centimeters long, weathered, fractured, and embedded with marine life scars, it belonged to one of the ocean’s most elusive and colossal inhabitants: a sperm whale. It was found not on a coast or seabed but inland, in the Copper Age mega-site of Valencina de la Concepción–Castilleja de Guzmán, southwest of Seville. It was, as researchers would soon discover, the first sperm whale tooth from the Iberian Peninsula ever uncovered from this era—and only the second of its kind found in all of Neolithic Europe.

A Monumental Site, A Singular Find

The discovery of the tooth adds a surprising new thread to the already rich tapestry of the Valencina archaeological site. Valencina is no ordinary dig. Spanning hundreds of hectares, it is one of the largest Copper Age sites in Europe and a place where life, death, and ceremony left deep and enduring marks in the soil. The site gained attention with the discovery of La Pastora, a tholos-type megalithic monument whose intricate underground chambers spoke of ritual, remembrance, and power.

What made the sperm whale tooth particularly extraordinary wasn’t just its rarity—it was the story it told about human curiosity, symbolic thinking, and a relationship with nature that defied easy categorization.

Dr. Samuel Ramírez-Cruzado Aguilar-Galindo, the lead researcher on the project, recognized the importance of the find almost immediately. Morphological analysis confirmed its origin: the tooth of an adult sperm whale. But this was no museum specimen. Its surfaces were marked with evidence of a journey—one that took it from the deep ocean floor to a sacred human site, from whale to wonder.

From Ocean Depths to Human Hands

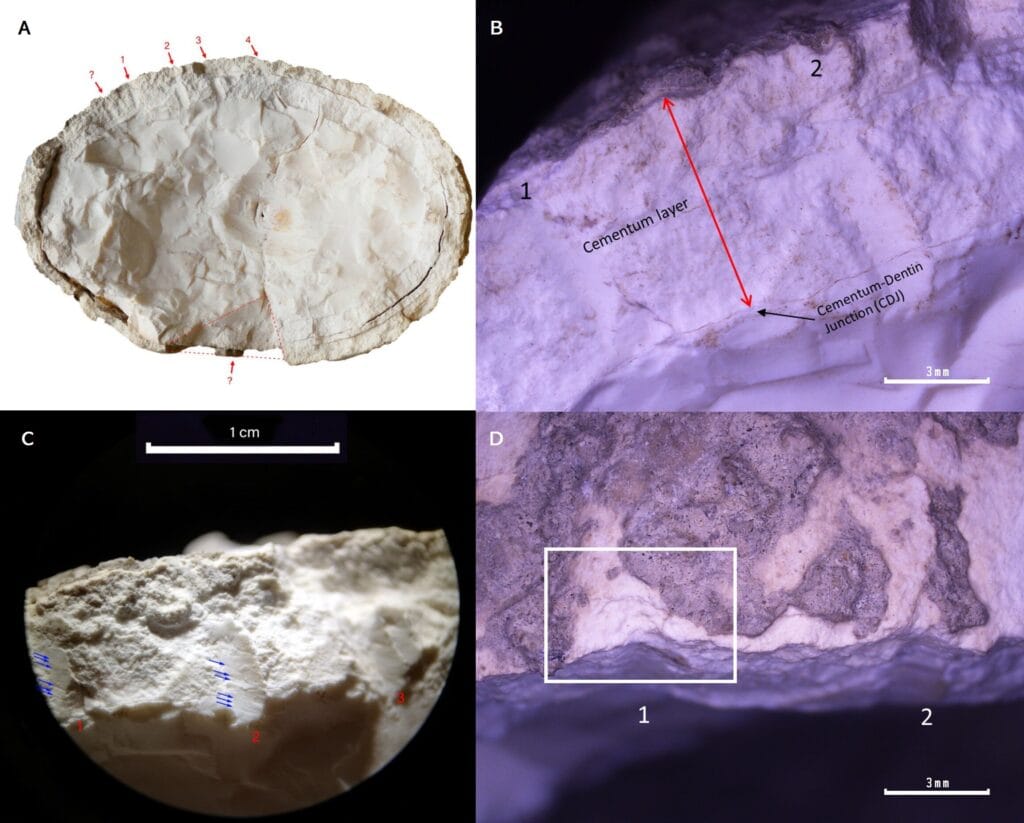

The tooth’s condition offered a rare opportunity for scientists to reconstruct its path. On the labial (outer) side, heavy wear indicated that the tooth had spent decades inside the mouth of a mature whale. A smoothed fracture on the lingual (inner) side suggested it had broken during the animal’s lifetime, possibly while hunting or navigating its vast, pressurized habitat.

But the story didn’t end with the whale’s death.

Taphonomic analysis—the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized—revealed a striking sequence of post-mortem events. After the whale died, its body likely sank to the sea floor, where the tooth lay exposed. Marks on its surface suggest it was gnawed on by scavengers, likely sharks. Later, it was colonized by marine life, including gastropods and sponges. This once-living part of a colossal ocean predator became part of a thriving undersea ecosystem.

Then, something shifted. Perhaps a storm surged through the area. Maybe tectonic activity jolted the sediment. However it happened, the tooth was dislodged from its resting place and cast upward, onto a beach or rocky coastline where human hands eventually found it.

What those early people saw when they picked it up can only be imagined. A smooth, gleaming, conical object—half tool, half talisman. It may have seemed to them like a gift from the gods or a message from the deep.

Shaped by Tools, Charged with Meaning

What happened next shows clear signs of human involvement. The bottom half of the tooth had been carefully split using steady pressure and a chisel-like tool. This was not accidental breakage—it was deliberate modification.

But the tooth wasn’t transformed into a weapon or farming implement. It wasn’t carved into jewelry or a figurine. Instead, it was deposited—quietly, reverently—into a pit among other items of symbolic value. No human bones were nearby. This was not a burial.

These kinds of pits have been found across Neolithic and Copper Age Europe: clusters of high-value objects carefully placed underground. Archaeologists interpret them as ritualistic deposits, offerings of great social and spiritual weight. Their purpose remains partly mysterious, but their existence hints at a culture that practiced intentional acts of devotion, memory, and perhaps, even awe.

In Valencina, such deposits often included bones from large animals. There is reason to believe these creatures were revered—not simply for their meat or hides, but for their grandeur, their mystery, and their symbolic power. Elephants, aurochs, and now, a sperm whale.

The addition of the whale tooth into this context was not random. It suggests that its finders recognized its origin or at least its uniqueness. As Dr. Ramírez-Cruzado Aguilar-Galindo puts it, “I support the idea that they knew the animal it came from—or at least that it came from a huge marine animal.”

And if they didn’t know exactly what a sperm whale was, they knew what it meant. That alone was enough.

Ancient Connections Across the Waves

The inclusion of a sperm whale tooth at Valencina doesn’t just speak to ritual—it speaks to contact, knowledge, and the deep interconnection of ancient communities. The tooth likely traveled dozens, if not hundreds, of kilometers before arriving at its final resting place.

There is compelling evidence that Neolithic and Copper Age communities maintained long-distance communication networks, both over land and via the sea. The presence of whale bone artifacts in other Iberian locations, particularly in Portugal, supports the idea that stories and objects moved from coast to interior—and back again.

It’s even possible that tales of great sea creatures were shared between communities. Perhaps people in landlocked villages knew of the giants that swam in the deep, carried in lore by traders or travelers. A sperm whale tooth might have seemed like proof of those legends—an object imbued with narrative and memory.

“The interesting thing about both teeth,” notes Dr. Ramírez-Cruzado Aguilar-Galindo, referencing the only other known Neolithic sperm whale tooth, found in Monte d’Accoddi (Sardinia), “is that they are the only sperm whale teeth from the Neolithic-Chalcolithic time found in archaeological contexts in Europe, at the moment. Both were found in very important places—almost sacred, I would say—which speaks of the importance given to these pieces.”

What a Tooth Can Teach Us

The Valencina sperm whale tooth does more than illuminate a forgotten moment in prehistory. It challenges our assumptions about what ancient people knew, valued, and believed. It collapses the boundary between sea and land, between living animal and ritual object, between nature and culture.

It also reminds us that humans have long sought meaning in the world around them—not just through language, but through the quiet power of objects. A single tooth, bearing the scars of the sea and the hands of its collectors, can tell a story that spans species, ecosystems, and civilizations.

More than 4,000 years later, we’re just beginning to listen.

Reference: Ramírez-Cruzado Aguilar-Galindo et al, From the jaws of the “Leviathan”: A sperm whale tooth from the Valencina Copper Age Megasite, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0323773