In a discovery that could reshape how we track and battle mosquito-borne diseases, an international team of scientists has found that mosquitoes are far more adaptable in their feeding habits than previously believed. The findings, published in Global Ecology and Biogeography, upend the long-standing assumption that mosquitoes target specific hosts predictably. Instead, these tiny disease carriers appear to be ecological opportunists, their appetites influenced by the shifting winds of climate, landscape, and the species around them.

A Global Investigation into What Mosquitoes Really Eat

At the heart of this revelatory study lies a staggering data set: more than 15,600 mosquito blood-meal records drawn from around the world. Using cutting-edge, broad-spectrum molecular DNA analysis, researchers were able to peer inside the bellies of six globally significant mosquito species and reveal exactly what—and who—they’d been feeding on.

Led by Dr. Konstans Wells from Swansea University, the team’s work marks the first major global study of mosquito host choice using modern universal DNA methods. The results paint a complex, dynamic picture of mosquito feeding behavior—one that carries major implications for global public health.

“Female mosquitoes have long been known to show preferences for certain hosts,” Dr. Wells explained. “But what surprised us is the sheer plasticity in their behavior—how their actual host choices change across regions depending on local environmental conditions.”

Not Just a Taste for Humans

The data shattered any notion of consistency in mosquito behavior. Culex mosquitoes, for example, showed an astonishing breadth of diet—feeding on between 179 and 321 different species. These included birds, reptiles, mammals, and amphibians. Aedes mosquitoes, which are notorious for spreading dengue and Zika, had a narrower but still impressive range of 26 to 65 species. The Anopheles genus, which includes the malaria vector, had the most restricted preferences—feeding on 7 to 29 species depending on region.

Such variability upends the conventional wisdom that mosquitoes have narrow ecological niches. Instead, they behave more like shape-shifting predators, adapting to what’s available in their environment.

“This means we can no longer simply assume that if humans are around, mosquitoes will prefer to feed on them,” said Dr. Nicholas Clark, co-author from the University of Queensland. “In some regions, they may prefer cattle or wild animals instead. In others, people are the main course.”

How Climate and Livestock Shape Mosquito Diets

Environmental context, it turns out, matters greatly. The team found that climate, land use, and livestock density all significantly influenced mosquito host choices.

In arid regions where water is scarce and human settlements are dense, mosquitoes were more likely to feed on people. In pastoral areas rich with cattle or goats, the insects shifted to animals. Rising temperatures and land-use changes also appeared to alter feeding patterns in unpredictable ways, a worrying trend in the context of climate change.

“What this tells us is that mosquito feeding behavior isn’t just about biology—it’s about ecology,” said Dr. Wells. “It’s about how mosquitoes interact with the world around them. And that world is changing fast.”

An Undergraduate Spark That Ignited Global Insight

Remarkably, the seed of this global study was planted by an undergraduate student. Meshach Lee, then studying at Swansea University under the mentorship of Dr. Wells, noticed something peculiar while analyzing mosquito studies for his dissertation. The insects’ host choices weren’t as uniform as the literature often implied.

“The variation in feeding behavior across regions was striking,” Lee said. “Some species fed on livestock in one place and on birds in another. That inconsistency intrigued me.”

His early analysis hinted at a much bigger story—one the team would eventually uncover by bringing together data from dozens of studies worldwide.

Why This Matters for Global Health

Behind the scientific intrigue lies a sobering reality: mosquitoes are among the deadliest animals on Earth. They are vectors for malaria, dengue, Zika, yellow fever, West Nile virus, and many other illnesses that affect millions of people each year.

Accurately predicting which hosts mosquitoes are feeding on is essential for tracking disease outbreaks, designing interventions, and targeting control strategies. If the insects are more flexible than expected, current models of disease spread could be oversimplified or even flawed.

“This study is a wake-up call,” said Dr. Richard O’Rorke, co-author from the University of Auckland. “We’ve been assuming a static picture of mosquito behavior when the reality is far more complex. If we want to effectively combat diseases like malaria or dengue, we need to update our understanding.”

The DNA That Changes Everything

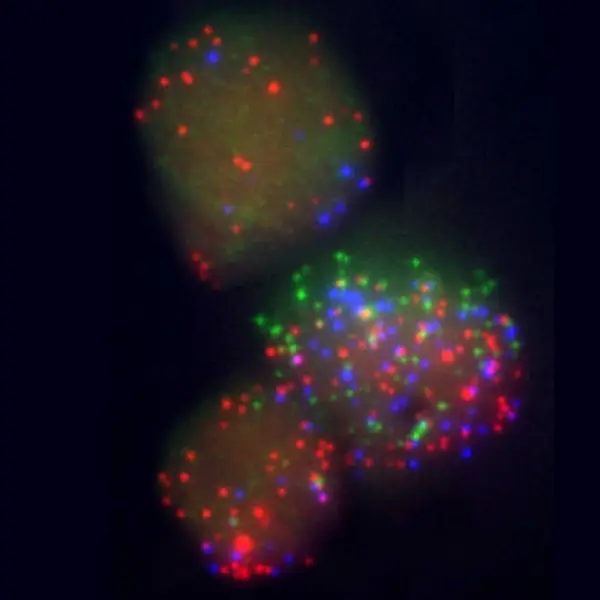

Central to the study’s breakthrough is the use of broad-spectrum molecular methods—universal DNA barcoding tools that allow scientists to identify mosquito blood meals with unprecedented precision.

In older studies, researchers often used narrow techniques that only detected a small number of host species—usually the ones they were already looking for. But the new methods cast a much wider net, capturing a fuller picture of mosquito diets.

“Without these tools, we would never have seen the diversity we see now,” Dr. Tamsyn Uren Webster of Swansea University noted. “It’s like going from a blurry snapshot to a high-resolution image. Suddenly, the behavior of these insects becomes much clearer—and much more fascinating.”

The Challenge Ahead: Standardization and Prediction

Despite the study’s insights, major challenges remain. The researchers emphasize that a lack of standardization in how blood-meal studies are conducted and reported continues to hinder accurate comparisons.

“Too many studies use different methods, or fail to report environmental context,” Dr. Wells explained. “We need a unified global standard—consistent DNA techniques, better metadata, and integration with ecological data.”

Only then, the team argues, can we begin to build accurate, predictive models of mosquito feeding behavior—models that can help anticipate where outbreaks might strike next.

A Complex Web in a Warming World

The study comes at a time of growing concern over climate-driven shifts in vector-borne diseases. As temperatures rise, mosquito habitats are expanding into new regions. Diseases once confined to the tropics are appearing in places like southern Europe and parts of North America.

In this context, understanding mosquito behavior becomes more urgent than ever.

“We’re seeing the playing field change before our eyes,” said Dr. Clark. “Mosquitoes are moving into new ecosystems. Their host choices are shifting. If we don’t keep up, we’ll be playing catch-up with diseases that spread faster than we can react.”

Implications for the Future of Surveillance

The findings carry major implications for global health policy and disease surveillance. The authors hope their research will inform smarter, more adaptive strategies for mosquito monitoring—ones that consider ecological variability rather than relying on assumptions.

This includes better integration with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, especially the goal of ensuring “good health and well-being” worldwide. Mosquito-borne diseases remain one of the largest public health burdens in many low- and middle-income countries.

“Science like this shows how dynamic nature is,” said Dr. Wells. “And if we want to protect human health in the face of that dynamism, our tools and policies need to be just as flexible.”

A Story of Blood, Climate, and Survival

At its core, the study is a reminder that mosquitoes are not mere nuisances. They are complex organisms navigating a world of changing climates, shifting landscapes, and diverse hosts. Their choices of whom to bite are not fixed—they are decisions molded by survival.

That flexibility, once invisible to science, is now laid bare by molecular tools and global cooperation. And with it comes a new responsibility: to rethink how we battle the diseases they carry.

Because in the intricate dance between humans and mosquitoes, knowing who’s biting whom might be the key to staying one step ahead.

Reference: Meshach Lee et al, Diversity and Plasticity in Mosquito Feeding Patterns: A Meta‐Analysis of ‘Universal’ DNA Diet Studies, Global Ecology and Biogeography (2025). DOI: 10.1111/geb.70077