Evolution is one of the most powerful and awe-inspiring concepts in all of science. It tells the story of how life came to be in its spectacular diversity—from bacteria to butterflies, from jellyfish to giraffes, from dinosaurs to us. Yet, despite being one of the most thoroughly tested and confirmed scientific theories, evolution is also one of the most widely misunderstood.

Perhaps it’s because the idea seems too slow and sprawling for our fast-paced world. Or perhaps it’s because it challenges deeply held beliefs and forces us to see ourselves not as the center of the universe, but as part of a long, branching tree of life. Evolution is not a theory of chaos or randomness; it is a story of deep time, subtle change, fierce struggles, and surprising beauty. But too often, its message gets lost in confusion.

To truly understand evolution, we must first unlearn some of the most common myths that surround it. These misunderstandings not only obscure the truth but rob us of the profound sense of connection and wonder that evolutionary thinking can offer. The journey begins by diving into the heart of these misconceptions—and replacing them with the clarity of science.

Evolution Is Not “Just a Theory”

Perhaps the most common misconception is the idea that evolution is “just a theory”—a hunch, a guess, or an unproven idea. In everyday conversation, the word “theory” often carries that casual meaning. But in science, a theory is something far more powerful. A scientific theory is a comprehensive explanation of some aspect of the natural world, supported by a vast body of evidence, tested through observation and experiment, and capable of making accurate predictions.

In this sense, the theory of evolution is as well established as the theory of gravity or the theory of relativity. You don’t hear people say gravity is “just a theory” while holding their coffee cup aloft. And yet, in biology, people routinely dismiss evolution with the same phrase—often out of misunderstanding, not malice.

The evidence for evolution is overwhelming. It comes from fossils, genetics, anatomy, embryology, and even biogeography. It unites everything we know about living organisms into one coherent framework. Calling it “just a theory” does a disservice not only to evolution but to the very meaning of science itself.

Evolution Does Not Say Humans Came From Monkeys

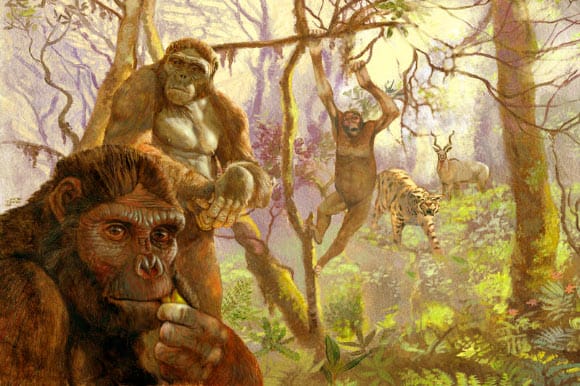

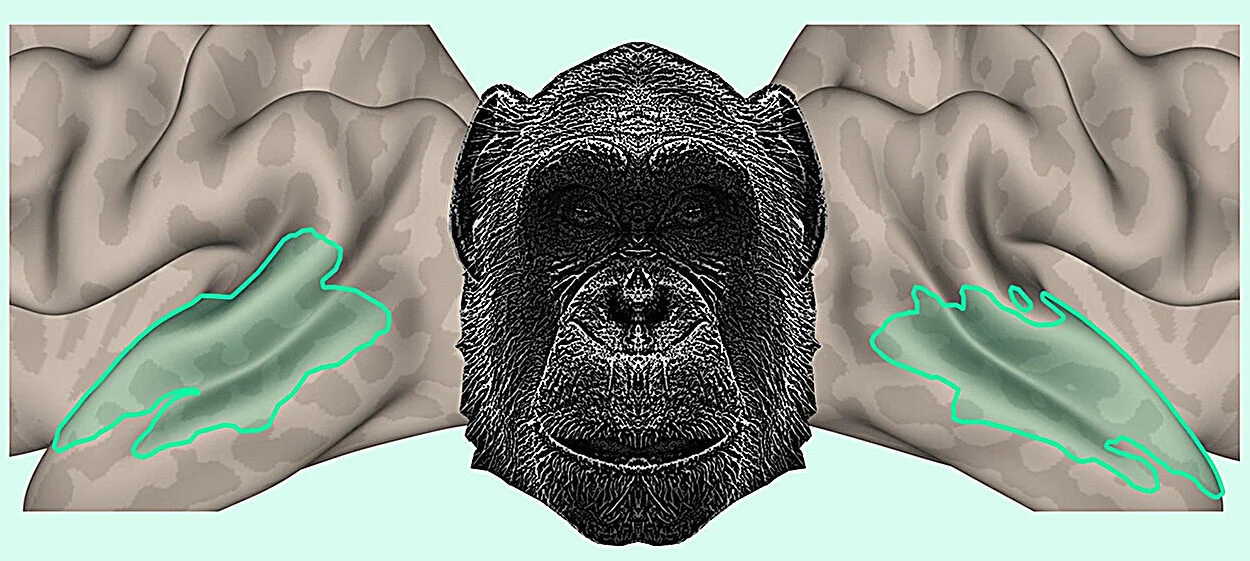

This misunderstanding is perhaps the most persistent. It’s repeated in cartoons, debates, and even classrooms: the claim that evolution teaches that humans evolved from monkeys. But evolution never said that. What it actually says is far more interesting—and far more humbling.

Humans and modern monkeys share a common ancestor. That means that if you go back far enough in time, there was a species—not quite human, not quite monkey—that gave rise to separate lineages. One of those lineages eventually led to today’s monkeys, and the other led to us. Monkeys didn’t turn into humans, and we didn’t turn into them. We are evolutionary cousins, not ancestors and descendants.

The confusion comes in part from the human tendency to think hierarchically: if we exist and monkeys exist, and if we are “more advanced,” then we must have come from them. But evolution doesn’t work in ladders; it works in branches. The tree of life is full of twists and forks, not simple vertical lines.

Natural Selection Is Not Random

Another common myth is that evolution is entirely random. People imagine a chaotic process with no direction, no order, and no sense. But that’s not what Darwin proposed. And it’s not what modern evolutionary biology supports.

Mutation—the source of genetic variation—is indeed random. Mutations occur because of copying errors, environmental damage, or molecular accidents. But natural selection, the driving force of evolution, is not random. It is an editing process. Nature selects for traits that enhance survival and reproduction, and against those that are harmful or neutral in a given environment.

If a mutation gives an animal sharper vision, it may help it catch prey more effectively or avoid predators more easily. That individual will likely leave more offspring, passing on the gene for sharper vision. Over generations, the population may evolve better eyesight. This isn’t random; it’s directional, though not goal-oriented.

Evolution is like a sculptor blindfolded by time. The chisel of natural selection carves slowly, but with astonishing precision—guided not by foresight, but by the immediate realities of survival.

Survival of the Fittest Is Not About Strength

Darwin himself rarely used the phrase “survival of the fittest.” It was popularized later, and unfortunately, it led to generations of misunderstanding. Many people think “fittest” means the strongest, the fastest, or the most aggressive. In fact, “fitness” in evolutionary terms means reproductive success.

An organism is “fit” if it leaves more offspring in the next generation. That could mean being stronger, but it could also mean being sneakier, more nurturing, better camouflaged, or just lucky enough to avoid predators. In some species, the fittest individuals are those that form alliances. In others, they’re the ones that care most for their young.

The cheetah is fast, yes—but the sloth, slow and deliberate, has been around for millions of years, perfectly adapted to its leafy life. In evolution, strength is just one of many strategies, and not always the most successful one.

Evolution Has No Ultimate Goal

One of the most deeply ingrained myths about evolution is that it is a progressive march toward perfection. People often speak as if evolution has a destination—humans, for example—and everything else is just on its way there. This is not only scientifically wrong, but it reflects an old anthropocentric bias: the belief that humans are the pinnacle of life.

Evolution has no foresight, no plan, and no direction toward “better” or “more evolved.” Organisms evolve simply to be well suited to their environment at that moment. If conditions change, what was once an advantage may become a liability.

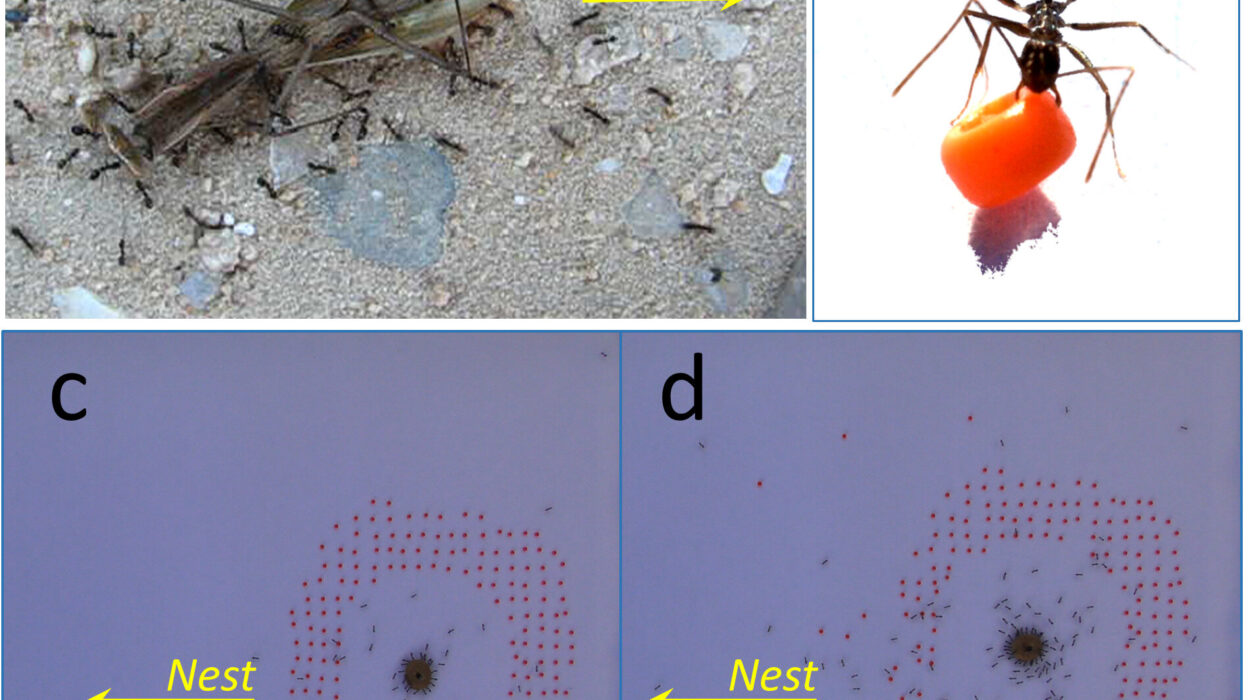

Sharks, ants, crocodiles, and cyanobacteria have changed little over hundreds of millions of years—not because they’re primitive, but because they’re perfectly adapted to their ecological niches. Evolution is not about getting smarter, taller, or more complex. It’s about being good enough to reproduce in a given context. That’s it.

We are not evolution’s final product. We are a snapshot—a temporary bloom on a vast and branching tree. Evolution continues, for us and for everything else.

Individuals Don’t Evolve—Populations Do

Sometimes the language of evolution trips people up. We say that an animal “evolved thicker fur” or that a plant “evolved resistance to drought.” But evolution doesn’t happen to individuals. It happens to populations over generations.

A single giraffe doesn’t stretch its neck to reach higher leaves and then pass that longer neck to its offspring. That was an old idea proposed by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, and though he was a pioneer in thinking about change over time, that idea turned out to be incorrect.

Instead, within a population of giraffes, there may be natural variation: some necks slightly longer than others. If longer-necked giraffes get more food and survive better, they may reproduce more. Over generations, the gene pool shifts, and the average neck length increases. That’s evolution in action—not visible in one animal’s lifetime, but undeniable over time.

Evolution Doesn’t Always Lead to Complexity

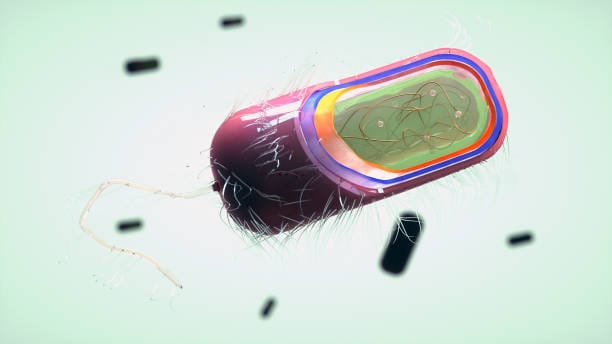

Another widespread belief is that evolution always leads from simplicity to complexity. While it’s true that life started with simple, single-celled organisms and eventually gave rise to multicellular beings like us, this is not a universal rule.

In fact, many evolutionary pathways lead to greater simplicity. Parasites often lose complex systems they no longer need, relying instead on their hosts. Cave-dwelling animals lose their eyesight. Bacteria shed genes when they’re no longer necessary.

Complexity is not inherently better. It’s just one possible outcome. Evolution is about efficiency, not extravagance. If a simpler organism reproduces more effectively, it wins the evolutionary game.

There Are No “Missing Links”

Fossils are often referred to as “missing links,” as if we’re looking for a single creature that fills a gap between species—half monkey, half man; half fish, half amphibian. But evolution doesn’t work like that. Every species is a link. And no link is missing; we just haven’t discovered all of them yet.

The fossil record is incomplete—not because evolution didn’t happen, but because fossilization is a rare and delicate process. Most creatures decay or are eaten before their remains can turn to stone. But even with these gaps, the record we do have shows a clear pattern of gradual change.

Transitional fossils exist in abundance. Tiktaalik bridges the gap between fish and land animals. Archaeopteryx shows the connection between dinosaurs and birds. Australopithecus helps reveal the story of human evolution. These aren’t “missing” links—they’re beautiful, tangible evidence of change over time.

Evolution Is Not the Same as Origin of Life

Another point of confusion is the belief that evolution tries to explain how life began. It does not. Evolution explains how life changes once it exists—not how it came to be in the first place.

The origin of life is a separate but equally fascinating field of study called abiogenesis. Scientists study how simple molecules could have organized themselves into self-replicating systems, perhaps in deep-sea hydrothermal vents or on the surfaces of ancient minerals.

While we don’t yet have a full picture of life’s beginnings, the two fields—evolution and abiogenesis—address different questions. Evolution picks up the story after the first living things appear, and it tells the tale of how those organisms diversified into everything we see today.

You Can See Evolution Happening Today

Some people dismiss evolution because they think it’s too slow to observe. They imagine that it only happened long ago, in the age of dinosaurs and trilobites. But evolution is happening right now, all around us—and sometimes startlingly fast.

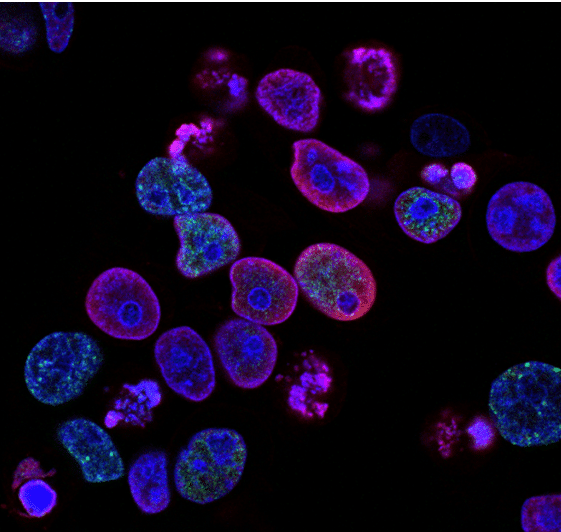

Bacteria evolve resistance to antibiotics within years or even months. Insects evolve resistance to pesticides. Viruses like the flu and COVID-19 mutate and shift, requiring new vaccines. These are not theoretical changes; they’re real, measurable adaptations that pose challenges to medicine and agriculture.

Even in larger animals, evolution can be surprisingly rapid. Birds change their migratory patterns. Fish adjust their size and breeding habits in response to overfishing. Urban wildlife evolves new behaviors to survive in concrete jungles.

We are not just studying evolution—we are living it.

Understanding Evolution Brings Us Closer to Life

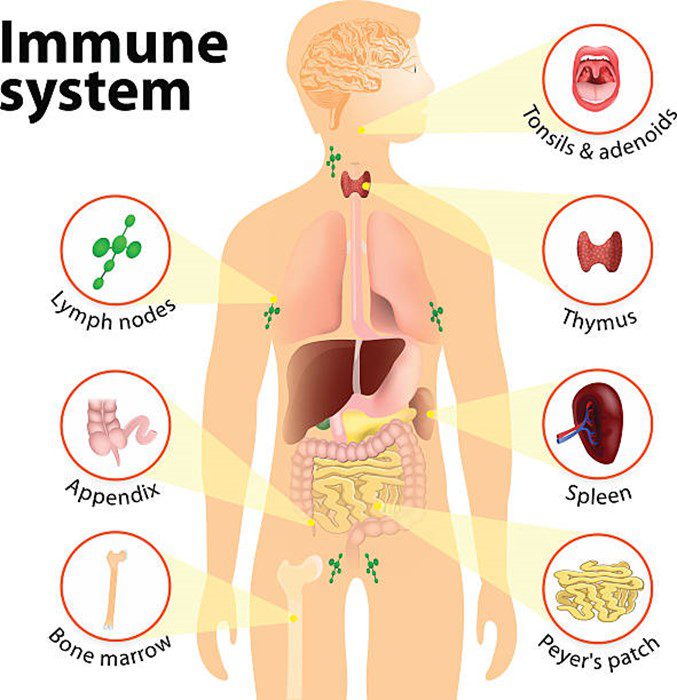

Misunderstandings about evolution don’t just lead to poor science education. They rob us of something deeper: the emotional and philosophical weight of evolutionary thinking. Evolution tells us that we are part of something vast and ancient. That our bodies carry echoes of fish, reptiles, and primates. That we are not separate from nature, but born of it.

When you look in the mirror, you are seeing the product of millions of years of tiny changes. Your bones are variations on patterns seen in whales and bats. Your DNA holds secrets shared with yeast and oak trees. Your emotions, your fears, your desires—they’re shaped by evolutionary forces that stretch back to when our ancestors first stood upright on the African savanna.

To understand evolution is to understand ourselves. Not just where we came from—but how we became who we are.

The Power of Teaching It Right

Fixing the misconceptions around evolution isn’t just about correcting facts. It’s about awakening minds. When students are taught that evolution is dry, controversial, or uncertain, they miss out on one of the greatest stories ever told.

But when it’s taught with accuracy and wonder—with fossils and genes, with logic and love—students begin to see the world differently. They begin to see patterns in the chaos. Connections in the diversity. And they begin to ask questions of their own.

Evolution isn’t a cold, mechanical process. It’s a story of resilience. Of organisms adapting, surviving, thriving, or failing. It’s a story of tiny chances leading to immense changes. It is, in many ways, the poetry of biology.

To teach evolution well is to give people a map—not just of life’s past, but of its possible futures.

The Journey Continues

Evolution is not over. It never ends. As long as life exists, it will keep changing. Some lineages will go extinct. Others will flourish. New species will emerge, shaped by their environments, by their interactions, and by chance.

We may not see humans growing wings or reading each other’s thoughts in the next few generations. But evolution continues quietly, reshaping the genetic tapestry of every living thing—including us.

In understanding evolution, we are not degrading humanity. We are elevating life itself. We are learning to read the signature of deep time in the shape of a bird’s beak, in the pattern of a butterfly’s wing, in the structure of our own hands.

And perhaps, in doing so, we find ourselves more connected to the world around us—not above it, but within it.

That is the true power of evolution. Not as a threat to meaning—but as a source of it.