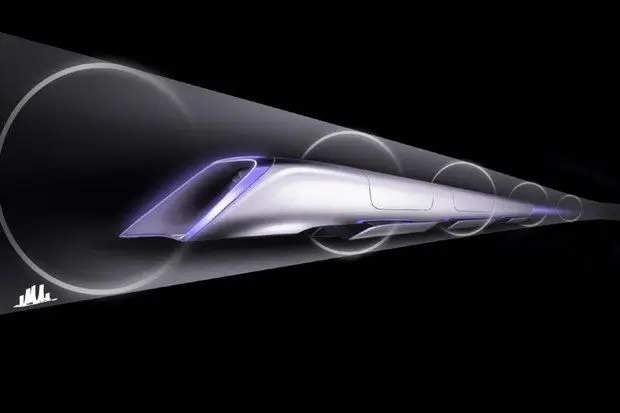

The idea of traveling faster than an airplane while remaining safely on the ground has long belonged to the realm of science fiction. Yet the concept known as the Hyperloop brings this vision into the domain of serious scientific and engineering discussion. Hyperloop proposes a transportation system in which passenger or cargo pods travel at near-supersonic speeds through long, sealed tubes maintained at extremely low air pressure. The promise is dramatic: journeys that take hours today could be reduced to minutes, reshaping how cities connect, how economies function, and how humans experience distance.

At its heart, Hyperloop is not magic, nor is it an entirely new invention. It is a carefully orchestrated application of well-established physical principles, especially those governing motion, pressure, friction, and energy. What makes Hyperloop fascinating is how these principles are combined and pushed to their practical limits. To understand Hyperloop, one must understand the physics of vacuums, the nature of drag, the challenges of stability at high speeds, and the subtle interplay between energy efficiency and safety. This article explores Hyperloop not as a futuristic fantasy, but as a deeply physical idea rooted in the laws that govern our universe.

The Fundamental Problem of High-Speed Ground Travel

Ground transportation faces a persistent physical obstacle: resistance. When a vehicle moves along the Earth’s surface, it must overcome friction with the ground and drag from the air. At low speeds, these forces are manageable. At high speeds, they become dominant, demanding enormous amounts of energy and creating significant engineering challenges.

Air resistance, or aerodynamic drag, increases roughly with the square of velocity. This means that doubling speed requires roughly four times as much force to overcome drag. At the speeds of modern high-speed trains, air resistance already accounts for the majority of energy consumption. Beyond a certain point, pushing faster becomes economically and physically inefficient.

Traditional rail systems mitigate some resistance through streamlined designs, but they remain constrained by the density of the atmosphere. Aircraft avoid ground friction by flying, but they encounter drag at high altitude and must expend large amounts of energy to stay airborne. Hyperloop addresses this problem by changing the environment itself. Instead of fighting air, it removes most of it.

The Physics of Vacuum and Low-Pressure Environments

A vacuum, in strict physical terms, is a region with no matter. Perfect vacuums do not exist outside of idealized theory, but engineers can create low-pressure environments where the density of air is drastically reduced. Hyperloop systems aim to operate in such low-pressure tubes, often described as near-vacuum conditions.

Air pressure is a measure of how many gas molecules collide with a surface per unit area. At sea level, air pressure is high because countless molecules constantly strike objects. These collisions are what produce aerodynamic drag. By lowering air pressure inside the Hyperloop tube, the number of molecular collisions decreases, and drag is reduced accordingly.

From a physics perspective, this is an elegant solution. Drag force depends directly on air density. If air density is reduced by a factor of one thousand, drag force is similarly reduced. This allows pods to move at extremely high speeds without requiring prohibitive amounts of energy. The physics is straightforward, but implementing it on a continental scale introduces profound technical challenges, including maintaining structural integrity and preventing air leaks over hundreds of kilometers.

Motion Through a Near-Vacuum

In a near-vacuum environment, motion behaves very differently from what we experience in everyday life. Without significant air resistance, an object in motion tends to remain in motion, in accordance with Newton’s first law. Once accelerated to cruising speed, a Hyperloop pod would require very little additional energy to maintain that speed.

This characteristic makes Hyperloop appealing from an energy efficiency standpoint. Most of the energy is spent during acceleration and deceleration, rather than during sustained travel. In principle, regenerative braking systems could recover much of this energy during slowing, converting kinetic energy back into stored electrical energy.

However, low resistance also removes a natural stabilizing force. Air resistance provides damping, reducing oscillations and smoothing motion. In a near-vacuum, even small disturbances can persist. This places stringent requirements on guidance systems, track alignment, and control algorithms. Physics here becomes not only a tool for speed, but also a constraint that demands precision.

Levitation and the Elimination of Contact Friction

Reducing air resistance alone is not sufficient for extreme-speed ground travel. Contact friction between wheels and tracks would generate heat, wear, and mechanical instability at high velocities. Hyperloop concepts therefore typically involve some form of levitation, lifting the pod off the track to eliminate rolling friction.

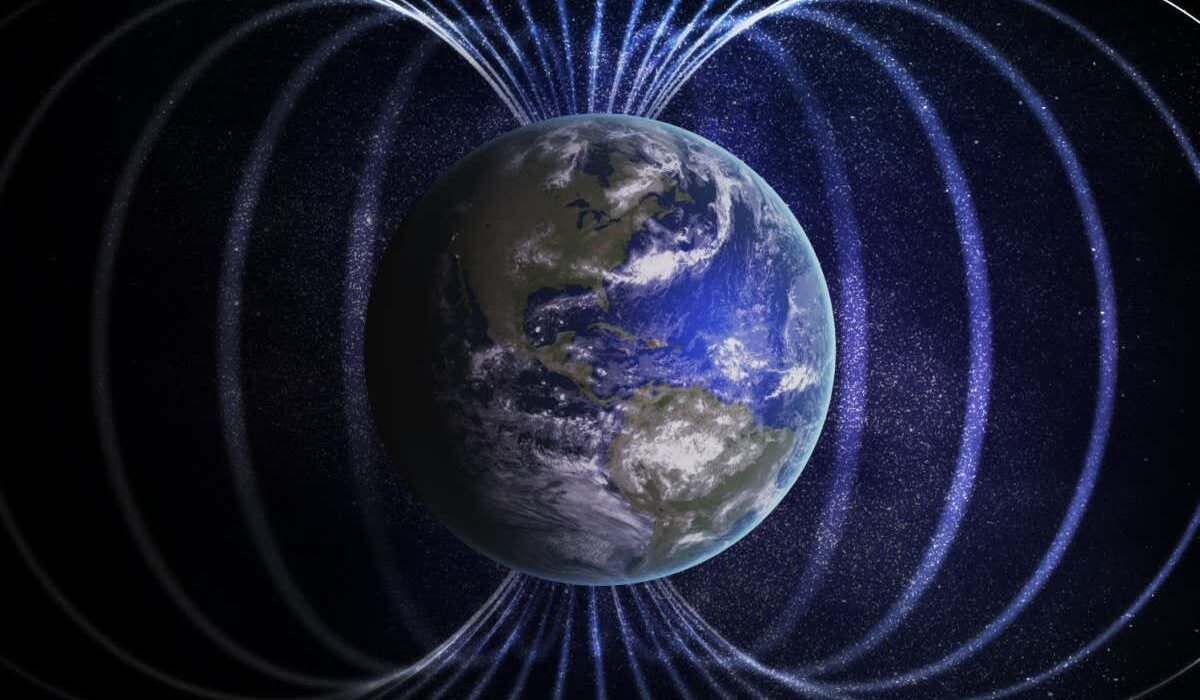

Several levitation approaches have been proposed, most commonly magnetic levitation. Magnetic forces arise from the interaction of electric currents and magnetic fields, governed by Maxwell’s equations. By carefully arranging magnets and conductive materials, it is possible to create repulsive or attractive forces that counteract gravity.

In magnetic levitation systems, stability is a subtle physical issue. Static magnetic fields alone cannot produce stable levitation without active control, a result known from classical physics. Practical systems rely on dynamic feedback, adjusting currents in real time to maintain stable suspension. In the controlled environment of a Hyperloop tube, such systems can be optimized for efficiency and safety.

Levitation transforms the nature of motion. Without contact friction, the primary remaining resistive forces are electromagnetic losses and residual air drag. The pod effectively glides through space, guided by invisible fields rather than physical rails.

Acceleration, Inertia, and Human Comfort

Physics does not only concern machines; it governs human bodies as well. Acceleration is a central consideration in Hyperloop design because it determines both travel time and passenger comfort. According to Newton’s second law, acceleration is directly related to force and mass. For a human passenger, acceleration is experienced as a force pressing against the body.

Excessive acceleration can cause discomfort or injury. Hyperloop systems therefore aim to limit acceleration to values comparable to those experienced in conventional transportation, such as airplanes during takeoff. This constraint means that reaching top speed requires a certain minimum distance, shaping the geometry of the system.

Deceleration presents similar challenges. Rapid stopping would subject passengers to large inertial forces. Physics dictates that safe, comfortable travel requires gradual changes in velocity, even in a system capable of extraordinary speed. The laws of motion impose a human-centered limit that no technological ambition can ignore.

The Energy Landscape of Hyperloop

Energy considerations lie at the core of Hyperloop’s appeal and its challenges. The kinetic energy of a moving object increases with the square of its velocity. At Hyperloop speeds, the energy stored in a pod’s motion is enormous. Managing this energy safely is a fundamental physical problem.

The advantage of low drag is that energy losses during cruising are minimal. The disadvantage is that any failure involving sudden energy release could be catastrophic. Physics demands robust safety systems capable of dissipating energy in controlled ways under all circumstances.

From an efficiency perspective, Hyperloop has the potential to outperform aircraft for medium-distance travel. Aircraft expend energy continuously to overcome drag and generate lift. Hyperloop pods, once accelerated, coast with minimal losses. If powered by renewable electricity, the system could offer a low-carbon alternative to current high-speed transport.

Structural Physics and the Challenge of Long Tubes

Maintaining a low-pressure environment over long distances introduces complex structural physics problems. The tube must withstand external atmospheric pressure, temperature variations, and mechanical stresses from the moving pods. Atmospheric pressure exerts a force of approximately one hundred thousand newtons per square meter. Over large surfaces, this force becomes immense.

From a physics standpoint, the tube functions as a pressure vessel operating in reverse. Instead of containing high internal pressure, it must resist external pressure trying to collapse it. Material selection, wall thickness, and geometric reinforcement are dictated by principles of elasticity, stress, and strain.

Thermal expansion adds another layer of complexity. Materials expand and contract with temperature changes, and over kilometers of tube, even small expansions can accumulate into significant displacements. Physics provides the equations to predict these effects, but engineering solutions must accommodate them without compromising the vacuum or alignment.

The Role of Electromagnetism in Propulsion

Propulsion in Hyperloop systems is often envisioned using linear electric motors. These devices use electromagnetic forces to accelerate pods along the tube without physical contact. The physics is an extension of conventional electric motors, but unrolled into a straight line.

Changing magnetic fields induce electric currents, and these currents interact with magnetic fields to produce force. By carefully synchronizing these interactions, a traveling magnetic wave can pull or push a pod forward. This method allows precise control of acceleration and speed, crucial for safety and efficiency.

Electromagnetic propulsion also integrates naturally with regenerative braking. When the pod slows, its kinetic energy can induce currents that feed electricity back into the system. This reversibility reflects a deep symmetry in physical laws, where energy transformations are governed by conservation principles.

Stability, Control, and the Physics of Feedback

High-speed travel in a near-vacuum demands exceptional stability. Even minute deviations in position or orientation can grow rapidly if not corrected. Physics describes this behavior through the mathematics of dynamical systems, where small perturbations can either decay or amplify depending on system design.

Active control systems rely on continuous measurement and adjustment. Sensors detect position, velocity, and acceleration, while control algorithms compute corrective forces. These systems operate within the limits set by signal speed, noise, and actuator response times, all of which are governed by physical laws.

The absence of significant damping means that stability must be engineered deliberately. This requirement transforms Hyperloop from a purely mechanical system into a cyber-physical one, where physics and computation are inseparably linked.

Safety in a Low-Pressure World

Safety concerns loom large in any discussion of Hyperloop. A low-pressure environment behaves very differently from normal atmospheric conditions. Sudden breaches could lead to rapid air influx, pressure waves, and structural stress.

Physics provides tools to analyze such scenarios. Fluid dynamics predicts how air would rush into a compromised section of tube, while wave mechanics describes how pressure disturbances propagate. These analyses inform the design of compartmentalization, emergency braking, and structural reinforcement.

Importantly, low pressure also reduces fire risk, as combustion requires oxygen. This unexpected benefit illustrates how altering one physical parameter can have cascading effects across a system. Safety in Hyperloop is not a single problem but a network of interrelated physical considerations.

Hyperloop and the Speed of Sound

Hyperloop speeds are often compared to the speed of sound, a fundamental physical limit in aerodynamics. In normal air, approaching or exceeding this speed generates shock waves and dramatic increases in drag. These effects are a consequence of how pressure disturbances propagate through a medium.

In a near-vacuum, the speed of sound is much lower because it depends on the density and temperature of the medium. With fewer molecules to transmit pressure waves, the conventional barriers associated with supersonic travel are largely avoided. This is one of the key physical insights behind Hyperloop’s feasibility.

Nevertheless, residual air still exists, and its behavior must be understood. Even small amounts of gas can produce complex flow patterns at high speeds. Detailed fluid dynamics modeling is essential to prevent unexpected instabilities.

Time, Distance, and the Human Experience of Speed

Physics tells us that speed is distance divided by time, a simple ratio with profound implications. Hyperloop compresses distance by reducing travel time, effectively reshaping geography. Cities separated by hundreds of kilometers could become functionally adjacent.

This transformation has an emotional dimension. Human perception of space and time is shaped by experience. When travel becomes faster, social, economic, and cultural relationships change. Physics enables this shift, but its consequences extend beyond equations.

At the same time, physics reminds us that speed is relative. Inside a smoothly accelerating Hyperloop pod, passengers may feel little sensation of motion once cruising speed is reached. This echoes Einstein’s insight that uniform motion is indistinguishable from rest, a principle that underlies much of modern physics.

Environmental Physics and Sustainability

Any new transportation system must be evaluated through the lens of environmental physics. Energy consumption, material use, and land impact are all governed by physical constraints.

Hyperloop’s potential efficiency arises from its low drag and regenerative energy systems. However, constructing long tubes requires significant materials and energy upfront. Physics-based life-cycle analysis is essential to determine whether long-term benefits outweigh initial costs.

Noise pollution is another consideration. In a sealed tube, noise from high-speed motion is contained, reducing external impact. This contrasts with aircraft, where sound waves propagate freely through the atmosphere. Once again, physics shapes not only performance but environmental compatibility.

The Limits Imposed by Physics

Despite its promise, Hyperloop is not free from physical limits. Material strength, energy storage, heat dissipation, and control precision all impose boundaries on what is achievable. Physics does not dictate a single outcome, but it defines a space of possibilities.

Understanding these limits is not a failure of imagination; it is an essential part of responsible innovation. By working within physical laws, engineers can identify feasible designs and avoid dangerous overreach. Hyperloop’s future depends not on ignoring physics, but on embracing it fully.

Hyperloop as a Continuation of Scientific Tradition

Hyperloop stands in a long tradition of transportation technologies shaped by physics, from steam locomotives to jet aircraft. Each advance required a deeper understanding of natural laws and a willingness to challenge existing assumptions.

What distinguishes Hyperloop is the extent to which it re-engineers the environment rather than the vehicle alone. By altering pressure, friction, and guidance, it redefines the physical context of motion. This approach reflects a mature stage of technological development, where physics is not merely accommodated but actively shaped.

Conclusion: Physics in Motion

Hyperloop is more than a technological proposal; it is a vivid demonstration of physics in action. It shows how abstract principles, developed over centuries of scientific inquiry, can converge into a bold vision for the future of transportation.

The physics of vacuums, high-speed motion, energy conservation, and electromagnetic forces are not distant academic topics here. They become the protagonists of a story about human ambition and restraint, about pushing boundaries while respecting natural law.

Whether Hyperloop ultimately becomes a widespread reality remains uncertain. What is certain is that its very conception reflects the power of physics to inspire, to challenge, and to connect human imagination with the fundamental workings of the universe. In contemplating Hyperloop, we are reminded that physics is not only about understanding what is, but about exploring what might be possible when knowledge, creativity, and respect for nature come together.