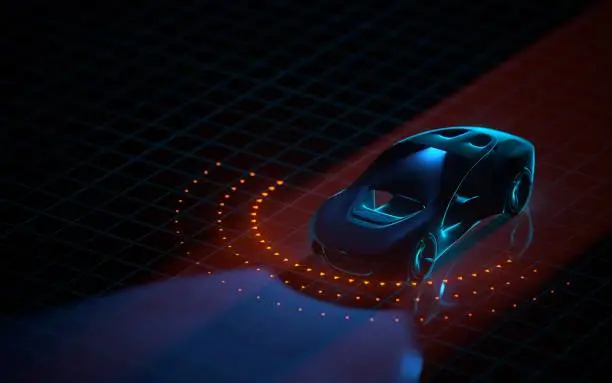

LiDAR, short for Light Detection and Ranging, has become one of the most evocative technologies of the autonomous age. Often described as the “laser eyes” of self-driving cars, LiDAR allows machines to perceive the world with extraordinary geometric precision. It does not merely see in the way a camera does, capturing color and texture, nor does it listen like radar, sensing motion through radio waves. Instead, LiDAR actively illuminates the world with pulses of laser light and measures how that light returns. From these measurements, it reconstructs a three-dimensional map of the surrounding environment with astonishing accuracy.

The emotional power of LiDAR lies in its promise. For decades, the idea of a car that could safely drive itself belonged to the realm of science fiction. LiDAR transformed that dream into an engineering problem. By giving vehicles a way to measure distance, shape, and spatial relationships in real time, LiDAR offered a sense of mechanical perception that felt almost biological. It is not an exaggeration to say that LiDAR changed how engineers think about machine vision, replacing flat images with living geometry.

The Physical Principle Behind LiDAR

At its heart, LiDAR is grounded in a simple and elegant physical idea: the speed of light is constant and finite. When a laser pulse is emitted from a LiDAR sensor, it travels outward at the speed of light, reflects off an object, and returns to the sensor. By measuring the time it takes for this round trip, the system can calculate the distance to the object with remarkable precision. This method, known as time-of-flight measurement, is a direct application of classical physics combined with modern electronics.

Because light travels incredibly fast, the time intervals involved are extraordinarily small, typically on the order of nanoseconds. Measuring such tiny durations requires highly precise clocks and sensitive detectors. Advances in semiconductor technology, photodetectors, and signal processing have made it possible to perform these measurements millions of times per second, enabling LiDAR systems to build dense and detailed maps of their surroundings in real time.

This process is emotionally compelling because it reveals how abstract physical constants become practical tools. The constancy of the speed of light, once a subject of philosophical debate and theoretical physics, becomes the foundation for a machine’s ability to “see” the world.

From Surveying the Earth to Navigating Streets

LiDAR did not originate in the automotive industry. Its roots lie in remote sensing, atmospheric science, and geospatial surveying. Early LiDAR systems were developed to measure the atmosphere, map terrain, and study forests and coastlines. Mounted on aircraft, LiDAR instruments could penetrate vegetation and reveal the shape of the ground beneath, revolutionizing fields such as archaeology, geology, and environmental science.

These early applications demonstrated LiDAR’s unique strength: its ability to measure shape and distance directly, independent of ambient light. Unlike cameras, which rely on sunlight or artificial illumination, LiDAR brings its own light source. This property made it attractive for autonomous vehicles, which must operate reliably in diverse lighting conditions, from bright midday sun to the deep darkness of night.

The transition from airborne surveying to automotive navigation required profound miniaturization and cost reduction. What was once a bulky, expensive instrument had to become compact, robust, and affordable enough to be mounted on a car and operate continuously in harsh conditions. This transformation is a story of engineering persistence, driven by the belief that precise spatial awareness is essential for safe autonomy.

How LiDAR Builds a Three-Dimensional World

A LiDAR system does more than measure a single distance. Modern automotive LiDAR sensors emit millions of laser pulses per second in different directions. Each returned pulse provides a point in space, defined by its distance and angle. Collectively, these points form what is known as a point cloud: a dense, three-dimensional representation of the environment.

Within this point cloud, objects emerge as clusters of points. A pedestrian appears as a vertical shape, a car as a rectangular volume, a building as a flat plane extending upward. Unlike a photograph, which compresses depth into a flat image, a LiDAR point cloud preserves the true spatial relationships between objects. This geometric fidelity is invaluable for navigation, obstacle avoidance, and decision-making.

The emotional resonance of this capability is subtle but profound. To watch a LiDAR visualization is to see the world stripped to its essence: no colors, no textures, only form and distance. It is a reminder that perception need not resemble human vision to be effective. Machines perceive the world in their own way, guided by physics rather than biology.

The Laser Itself: Wavelengths and Safety

The lasers used in automotive LiDAR systems are carefully chosen to balance performance, safety, and cost. Common wavelengths include around 905 nanometers and 1550 nanometers, both in the near-infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum. These wavelengths are invisible to the human eye, allowing LiDAR to operate without distracting drivers or pedestrians.

Safety is a central concern. Automotive LiDAR systems are designed to be eye-safe, meaning the power of the laser pulses is limited to levels that do not damage human eyes under normal operating conditions. This constraint influences system design, affecting range, resolution, and signal processing techniques.

The choice of wavelength also affects how the laser interacts with different materials. Some surfaces reflect infrared light efficiently, while others absorb or scatter it. Understanding these interactions requires a deep knowledge of optics and materials science, highlighting how LiDAR sits at the intersection of multiple physical disciplines.

Resolution, Range, and the Challenge of Detail

One of the key performance metrics of a LiDAR system is its resolution, both angular and spatial. Angular resolution determines how finely the sensor can distinguish objects at different directions, while spatial resolution determines how precisely it can measure distance. High resolution allows the system to detect small objects and subtle features, such as a curb or a partially obscured pedestrian.

Range is equally important. A self-driving car must be able to detect obstacles far enough ahead to react safely at highway speeds. Achieving long range requires sensitive detectors and powerful signal processing to extract faint reflections from distant objects, all while maintaining eye safety.

These requirements often conflict. Increasing range may reduce resolution, and improving resolution may limit range or increase cost. Designing a LiDAR system involves navigating these trade-offs, guided by physics, engineering constraints, and safety considerations. The result is a delicate balance, reflecting the complexity of translating physical principles into reliable machines.

Mechanical and Solid-State LiDAR

Early automotive LiDAR systems often relied on mechanical scanning. These systems used rotating mirrors or spinning assemblies to sweep laser beams across the environment, creating a 360-degree view. While effective, mechanical LiDAR introduced challenges related to durability, size, and cost.

In response, researchers and engineers began developing solid-state LiDAR, which minimizes or eliminates moving parts. Solid-state designs use techniques such as phased arrays, micro-electromechanical systems, or optical switching to steer laser beams electronically. These approaches promise greater reliability and easier integration into vehicle designs.

The evolution from mechanical to solid-state LiDAR mirrors a broader trend in technology: the move from macroscopic motion to microscopic control. It is a testament to how advances in materials science and microfabrication reshape what is physically possible.

LiDAR and the Problem of Interpretation

LiDAR provides raw geometric data, but raw data alone is not enough. A self-driving car must interpret the point cloud, identifying objects, predicting their motion, and making decisions accordingly. This interpretation relies on algorithms drawn from physics, statistics, and machine learning.

Segmentation algorithms separate the point cloud into meaningful components, distinguishing ground from obstacles, vehicles from pedestrians. Tracking algorithms estimate how objects move over time, while sensor fusion combines LiDAR data with information from cameras, radar, and other sensors.

This process underscores an important truth: perception is not just about sensing, but about understanding. LiDAR supplies precise measurements, but intelligence emerges from how those measurements are processed and interpreted. The emotional appeal of autonomous driving lies not only in the hardware, but in this synthesis of physics and computation.

LiDAR Versus Cameras and Radar

LiDAR is often discussed alongside cameras and radar, the other primary sensors used in autonomous vehicles. Each modality has distinct strengths and limitations. Cameras provide rich visual detail, capturing color, texture, and semantic information that LiDAR lacks. Radar excels at detecting objects in poor weather and measuring relative velocity.

LiDAR’s unique contribution is precise three-dimensional geometry. It measures distance directly, rather than inferring it from visual cues or Doppler shifts. This directness reduces ambiguity and simplifies certain perception tasks.

Rather than competing, these sensors complement one another. A robust autonomous system integrates data from all available sources, leveraging the strengths of each. This philosophy reflects a broader lesson of physics and engineering: complex problems are best addressed through multiple perspectives.

Weather, Noise, and the Real World

Real-world driving presents challenges that push LiDAR systems to their limits. Rain, fog, snow, and dust can scatter laser light, creating noise and reducing effective range. Highly reflective or absorbent surfaces can distort measurements, while direct sunlight can introduce background noise.

Addressing these challenges requires careful system design and signal processing. Techniques such as temporal averaging, adaptive thresholds, and sensor fusion help mitigate environmental effects. Understanding how light interacts with atmospheric particles and surfaces is essential, drawing on principles of scattering, absorption, and optical noise.

These difficulties add emotional weight to the story of LiDAR. The technology is powerful, but not magical. It must contend with the messy complexity of the real world, reminding us that autonomy is not achieved through a single breakthrough, but through incremental improvements and resilience.

The Cost Barrier and Technological Evolution

For many years, LiDAR was criticized for its cost. Early automotive systems were prohibitively expensive, limiting their deployment. Reducing cost required innovations in laser manufacturing, photodetectors, electronics, and system integration.

As production scales increased and designs matured, costs fell dramatically. Solid-state approaches promised further reductions by leveraging techniques similar to those used in consumer electronics. This economic evolution parallels the history of many transformative technologies, from computers to GPS.

Cost is not merely a financial issue; it shapes which technologies become widely adopted and which remain niche. The gradual democratization of LiDAR reflects the interplay between physics, engineering, and market forces.

LiDAR Beyond Self-Driving Cars

While self-driving cars have brought LiDAR into the public imagination, the technology’s reach extends far beyond automotive applications. LiDAR is used in robotics, drones, infrastructure monitoring, agriculture, and environmental science. It enables precise mapping of forests, glaciers, and urban environments, contributing to climate research and disaster response.

These broader applications reinforce the idea that LiDAR is not just a component of autonomous vehicles, but a general tool for spatial understanding. Its ability to measure the world with laser precision makes it a cornerstone of modern sensing technologies.

Ethical and Social Dimensions

As LiDAR enables machines to navigate human environments, it raises ethical and social questions. How should data be collected, stored, and used? What level of safety is acceptable for autonomous systems? How do we balance innovation with responsibility?

Physics alone cannot answer these questions, but it provides the foundation upon which they rest. Understanding what LiDAR can and cannot do is essential for informed public discourse and policy. The emotional stakes are high because the technology directly affects human lives.

The Future of LiDAR

The future of LiDAR is shaped by ongoing research and development. Improvements in resolution, range, and robustness continue, driven by advances in photonics and computation. Integration with artificial intelligence promises more sophisticated interpretation of sensor data, while new materials and fabrication techniques may further reduce cost and size.

There is also active debate about LiDAR’s long-term role in autonomous driving. Some argue that advances in camera-based systems could reduce reliance on LiDAR, while others maintain that precise depth sensing will always be essential. This debate reflects deeper questions about perception, redundancy, and safety.

LiDAR as a Symbol of Machine Perception

Beyond its technical details, LiDAR has become a symbol. It represents the moment when machines began to perceive the world in three dimensions, guided by the immutable laws of physics. It embodies the idea that understanding light, time, and space can lead to technologies that reshape society.

The emotional resonance of LiDAR lies in this fusion of abstraction and application. From the constancy of the speed of light to the practical challenge of navigating a busy street, LiDAR connects fundamental physics to human experience. It reminds us that scientific knowledge is not static, but alive, evolving, and deeply intertwined with our hopes for the future.

Conclusion: Seeing the World Through Light

LiDAR, the laser “eyes” of self-driving cars, stands at the crossroads of physics, engineering, and imagination. It transforms pulses of invisible light into maps of reality, enabling machines to move through the world with awareness and precision. In doing so, it reveals the enduring power of physical principles to shape technology and society.

To understand LiDAR is to appreciate how deeply physics penetrates modern life. It is a story of light and time, of measurement and meaning, of human curiosity harnessed through engineering. As autonomous systems continue to evolve, LiDAR will remain a testament to the idea that by understanding the fundamental workings of nature, we can teach machines to navigate the complexity of our world with care and intelligence.