The story of human biology has always been a story of limits. For most of history, genes were destiny—mysterious instructions locked inside cells, passed from one generation to the next, shaping bodies, abilities, vulnerabilities, and lives in ways that seemed immutable. Medicine could treat symptoms, alleviate suffering, and sometimes delay disease, but it could not rewrite the genetic sentences that lay at the root of many conditions. That boundary is now dissolving. CRISPR technology has transformed the idea of genetic intervention from distant speculation into a concrete scientific reality, offering humanity the unprecedented ability to edit its own DNA with precision, speed, and relative simplicity.

CRISPR is not merely a new laboratory tool; it represents a fundamental shift in how humans relate to their own biology. For the first time, altering the genetic code of living cells is no longer an extraordinary, highly specialized feat limited to elite laboratories. It has become accessible, programmable, and adaptable. This transformation raises extraordinary scientific opportunities and equally profound ethical questions. To understand how CRISPR is changing human DNA, one must explore its origins, its molecular logic, its medical promise, its risks, and its implications for the future of human identity.

The Genetic Code and the Meaning of DNA

DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, is the molecular archive of life. Encoded within its double-helical structure are the instructions that guide the development, function, and maintenance of every cell in the human body. DNA is composed of sequences of four chemical bases—adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine—arranged in precise patterns. These sequences form genes, which carry the information needed to build proteins, the molecular machines that perform most biological functions.

For decades, scientists could read DNA but could not easily change it. The completion of the Human Genome Project at the beginning of the twenty-first century provided a detailed map of human genes, but knowing the map did not mean being able to redraw it. Traditional genetic engineering techniques were slow, expensive, and imprecise, often requiring years of work to modify a single gene. The genome was readable, but largely untouchable.

CRISPR changed that balance. It transformed DNA from a static script into an editable text, allowing scientists to cut, remove, replace, or modify specific genetic sequences with remarkable accuracy. This shift has redefined the boundaries of genetics, turning what was once observational science into an interventionist one.

The Accidental Discovery That Changed Biology

The origins of CRISPR are surprisingly humble. It was not discovered as a tool for human gene editing, but as a curious pattern in bacterial DNA. In the late twentieth century, microbiologists studying bacteria noticed unusual repeating sequences in their genomes. These sequences, later named Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, appeared alongside fragments of viral DNA.

Over time, researchers realized that CRISPR was part of an ancient bacterial immune system. When a virus infects a bacterium, the bacterium can capture fragments of the viral DNA and store them in its own genome. If the virus attacks again, the bacterium uses these stored sequences to recognize and destroy the invader. This defense mechanism relies on specialized enzymes, including CRISPR-associated proteins such as Cas9, which act as molecular scissors.

The insight that transformed biology came when scientists realized that this natural system could be repurposed. If bacteria could be programmed to recognize and cut viral DNA, perhaps researchers could program the same system to cut any DNA sequence they chose. This realization opened the door to programmable gene editing, setting off a revolution that spread rapidly across the life sciences.

How CRISPR Works at the Molecular Level

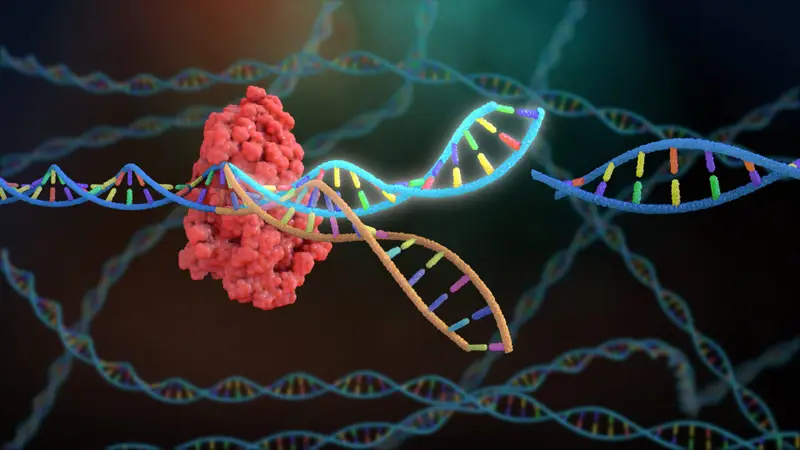

At its core, CRISPR is a guided cutting system. The most widely used version involves two key components: a guide RNA and a Cas enzyme, most commonly Cas9. The guide RNA is designed to match a specific DNA sequence. When introduced into a cell alongside Cas9, it directs the enzyme to the exact location in the genome that matches the guide sequence.

Once Cas9 reaches its target, it cuts both strands of the DNA double helix. This break triggers the cell’s natural DNA repair mechanisms. Cells can repair DNA breaks in two main ways. One method, called non-homologous end joining, simply reconnects the broken ends, often introducing small errors that can disable a gene. The other method, called homology-directed repair, uses a template to repair the break, allowing scientists to insert or replace specific genetic sequences.

This ability to harness the cell’s own repair machinery is what makes CRISPR so powerful. Rather than forcing changes onto DNA, CRISPR creates a precise opportunity for the cell to rewrite its own code. The result is a system that is efficient, flexible, and adaptable to a wide range of genetic targets.

From Laboratory Tool to Medical Breakthrough

The impact of CRISPR on biomedical research was immediate. Within a few years of its adaptation, laboratories around the world were using it to study gene function, create disease models, and explore potential therapies. What once required years of effort could now be achieved in weeks.

In medicine, CRISPR offers a fundamentally new approach to treating genetic disease. Many disorders, such as sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis, and certain forms of blindness, arise from specific mutations in single genes. In principle, correcting these mutations at the DNA level could provide a permanent cure rather than temporary symptom management.

Early clinical successes have demonstrated this potential. In some cases, patients’ cells are removed from the body, edited using CRISPR, and then reintroduced. This approach, known as ex vivo gene editing, allows for careful control and testing before the edited cells are returned to the patient. In other cases, CRISPR components are delivered directly into the body, targeting specific tissues.

These advances represent a shift from treating disease to correcting its root cause. Instead of managing the consequences of faulty genes, CRISPR-based therapies aim to fix the genetic errors themselves, redefining the goals of medicine.

Editing Blood Disorders and Inherited Diseases

One of the most promising areas of CRISPR application involves blood disorders. Diseases such as sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia are caused by mutations affecting hemoglobin, the protein responsible for carrying oxygen in red blood cells. These conditions have long been treated with supportive care, transfusions, or bone marrow transplants, each with significant limitations.

CRISPR has enabled a new strategy. By editing stem cells in the bone marrow, scientists can reactivate fetal hemoglobin production or correct the faulty gene directly. Edited cells can then produce healthy red blood cells, alleviating symptoms and potentially eliminating the disease.

These treatments are not theoretical. Clinical trials have shown that CRISPR-edited cells can persist in patients and provide lasting benefits. For individuals who have lived with chronic pain, fatigue, and medical complications, these advances represent not just scientific progress, but a transformation of daily life.

CRISPR and Cancer Therapy

Cancer is not a single disease, but a complex collection of genetic changes that allow cells to grow uncontrollably. CRISPR has become a powerful tool for understanding these changes and for developing new therapies.

In research settings, CRISPR allows scientists to systematically modify genes in cancer cells to identify which mutations drive tumor growth or resistance to treatment. This knowledge helps guide the development of targeted therapies.

In clinical contexts, CRISPR is being explored as a way to enhance immune cells used in cancer treatment. By editing genes in T cells, researchers can improve their ability to recognize and attack cancer cells. This approach builds on existing immunotherapies, offering a more precise and adaptable strategy for fighting cancer.

While challenges remain, including ensuring safety and preventing unintended effects, CRISPR has already reshaped the landscape of cancer research, accelerating discovery and expanding therapeutic possibilities.

Editing the Human Germline

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of CRISPR is its potential to edit the human germline. Germline cells, including eggs, sperm, and early embryos, carry genetic information that is passed on to future generations. Editing these cells would not only affect an individual, but their descendants as well.

In theory, germline editing could eliminate inherited diseases from family lines permanently. Conditions caused by single-gene mutations could be removed before birth, preventing suffering before it begins. This possibility is both inspiring and unsettling.

The ethical concerns are profound. Germline editing raises questions about consent, long-term safety, and the potential for unintended consequences that could propagate through generations. It also raises fears of misuse, including the possibility of genetic enhancement or the creation of social inequalities based on access to genetic modification.

The scientific community largely agrees that germline editing should be approached with extreme caution. While research continues under strict oversight, most countries prohibit clinical applications involving heritable genetic changes. CRISPR has made such changes technically possible, but society has not yet decided whether they should be allowed.

Accuracy, Limitations, and Risks

Despite its power, CRISPR is not perfect. One of the main concerns is off-target effects, where the Cas enzyme cuts DNA at unintended locations. Such errors could disrupt important genes or activate harmful pathways, including those related to cancer.

Advances in CRISPR design have significantly reduced these risks. Improved guide RNA selection, modified Cas enzymes, and new variants such as base editors and prime editors offer greater precision. These newer tools allow scientists to make specific changes to individual DNA bases without cutting both strands of the DNA helix, further improving safety.

Another challenge lies in delivering CRISPR components to the right cells in the body. Viruses are often used as delivery vehicles, but they can trigger immune responses or have limited capacity. Non-viral delivery methods are under development, but efficient and targeted delivery remains an active area of research.

Understanding these limitations is essential. CRISPR is a powerful technology, but it must be applied with rigorous testing, careful monitoring, and realistic expectations.

Beyond Disease: Enhancement and Human Identity

CRISPR’s ability to alter human DNA inevitably raises questions that go beyond medicine. If genes can be edited to prevent disease, could they also be edited to enhance traits such as intelligence, physical strength, or appearance? While such applications remain largely speculative, the possibility challenges traditional boundaries between therapy and enhancement.

Human traits are typically influenced by many genes interacting with environmental factors. Editing complex traits is far more difficult than correcting single-gene disorders. Nevertheless, the prospect of enhancement fuels ethical debates about fairness, diversity, and the meaning of being human.

There is also concern that genetic enhancement could exacerbate social inequalities. If access to genetic modification is limited to certain populations, it could create biological advantages that reinforce existing disparities. These concerns underscore the need for inclusive, transparent discussions about how CRISPR should be used.

CRISPR forces humanity to confront questions about self-determination and responsibility. Altering DNA is not just a technical act; it is a decision about what kinds of lives are valued and what kinds of differences are accepted.

Regulation and Global Responsibility

The global nature of science means that CRISPR’s impact cannot be confined to any single country. Genetic research crosses borders, and decisions made in one place can influence practices elsewhere. As a result, international cooperation is essential.

Regulatory frameworks for CRISPR vary widely. Some countries allow limited clinical use under strict oversight, while others impose broad prohibitions. International scientific organizations have called for shared ethical standards, particularly regarding germline editing.

Public engagement is also crucial. Decisions about altering human DNA affect society as a whole, not just scientists or policymakers. Transparent communication, education, and dialogue can help ensure that CRISPR’s development reflects shared values rather than narrow interests.

CRISPR and the Future of Medicine

The long-term implications of CRISPR for medicine are vast. As techniques improve, gene editing could become a routine part of healthcare, integrated into diagnostics, prevention, and treatment. Personalized medicine, tailored to an individual’s genetic profile, could move from concept to reality.

CRISPR may also transform how diseases are classified. Instead of grouping conditions by symptoms, medicine could focus on underlying genetic mechanisms, enabling more precise interventions. This shift would represent a profound change in medical practice, aligning treatment more closely with biological causes.

The integration of CRISPR with other technologies, such as artificial intelligence and advanced imaging, could further accelerate progress. Together, these tools may allow scientists to predict disease risk, design targeted interventions, and monitor outcomes with unprecedented accuracy.

The Emotional Weight of Genetic Change

Beyond laboratories and clinics, CRISPR carries emotional significance. For individuals living with genetic diseases, it represents hope where there was once resignation. For families affected by inherited conditions, it offers the possibility of breaking cycles of suffering.

At the same time, the ability to alter DNA can provoke anxiety and resistance. Genes are deeply tied to identity, ancestry, and the sense of self. Changing them can feel like altering something fundamental and sacred.

These emotional dimensions are not obstacles to progress; they are essential considerations. Science does not operate in isolation from human values, and the success of CRISPR will depend not only on technical achievement but on trust, empathy, and ethical integrity.

CRISPR as a Turning Point in Human History

CRISPR technology marks a turning point in the relationship between humans and their biology. For the first time, the genetic code that has shaped human evolution is no longer beyond deliberate modification. This shift carries immense promise and equally immense responsibility.

The power to change human DNA demands humility. Biology is complex, and unintended consequences are always possible. Yet refusing to explore this power would also carry costs, leaving preventable suffering unaddressed.

CRISPR is not destiny; it is a tool. How it reshapes humanity will depend on the choices societies make about its use. Guided by scientific rigor, ethical reflection, and a commitment to shared human values, CRISPR has the potential to alleviate disease, deepen understanding, and expand the horizons of medicine.

In learning to edit our own DNA, humanity is not just rewriting genes. It is redefining the limits of possibility, stepping into a future where biology is no longer merely inherited, but understood, guided, and, with care, transformed.