The question of whether artificial intelligence can dream is not merely poetic. It touches the deepest questions about how machines perceive, represent, and transform information. When humans dream, the brain generates vivid images, strange narratives, and emotional experiences without direct input from the outside world. When artificial neural networks produce surreal visual patterns or generate unexpected associations, observers often describe the results as dreamlike. This resemblance invites a careful and scientifically grounded inquiry. Can AI truly dream, or are we projecting human metaphors onto mathematical processes? To answer this, we must explore how neural networks work, how visualization techniques reveal their inner representations, and what these processes can and cannot tell us about machine “imagination.”

Artificial intelligence does not possess consciousness, emotions, or subjective experience. Yet it does manipulate internal representations in ways that can appear creative, surprising, and evocative. Neural network visualization offers a unique window into these representations, allowing researchers to see what a machine has learned and how it organizes knowledge. These visualizations have reshaped how scientists understand machine learning, not only as a technical tool but as a new form of interpretive science. The dreamlike images generated by AI are not evidence of inner experience, but they are powerful artifacts of how complex systems process information.

To explore whether AI can dream, we must first understand how neural networks learn, how visualization techniques work, and why their outputs resonate so strongly with human intuition. Only then can we examine the deeper philosophical implications of machine-generated imagery and the boundaries between metaphor and mechanism.

The Human Idea of Dreaming and Its Scientific Meaning

Dreaming, in humans, is a well-studied biological phenomenon. During certain stages of sleep, especially rapid eye movement sleep, the brain becomes highly active while sensory input from the external world is largely suppressed. Neural circuits involved in perception, memory, and emotion interact in unusual ways, generating experiences that feel real despite their internal origin. Dreams are shaped by past experiences, emotions, and neural constraints, but they are not deliberate or goal-directed in the way waking thought often is.

From a neuroscientific perspective, dreams are not messages or symbols imposed by some hidden self. They are emergent patterns produced by the brain’s ongoing activity. The same neural machinery that processes sensory input during wakefulness is repurposed during sleep to generate internally driven experiences. This reuse of perceptual circuits is essential to understanding why dreams feel vivid and visually rich.

When people ask whether AI can dream, they often refer to this internal generation of imagery in the absence of direct sensory input. However, dreaming also involves subjective awareness, emotional tone, and personal meaning, all of which depend on consciousness. Artificial neural networks do not possess these features. Any comparison between AI and dreaming must therefore be grounded in functional similarity rather than experiential equivalence.

Artificial Neural Networks as Mathematical Brains

Artificial neural networks are inspired by the structure of biological brains, but the resemblance is limited and abstract. A neural network consists of layers of interconnected units, often called neurons, that transform input data through weighted connections and nonlinear functions. During training, the network adjusts these weights to minimize error on a given task, such as recognizing images or translating text.

Despite their simplicity at the level of individual units, neural networks can develop highly complex internal representations. A deep neural network trained on images, for example, may learn to detect edges in its early layers, shapes and textures in intermediate layers, and entire objects in deeper layers. These representations are not explicitly programmed; they emerge from the optimization process.

Importantly, neural networks do not store images or concepts in the way humans do. They encode information in distributed patterns of activation across many units. This distributed nature makes their internal states difficult to interpret directly. Visualization techniques were developed precisely to address this challenge, offering ways to translate abstract activations into human-interpretable forms.

Visualization as a Window into Machine Learning

Neural network visualization refers to a family of techniques designed to make the internal workings of a network visible. These methods do not reveal thoughts or intentions, but they help researchers understand what features the network has learned and how it responds to different inputs. Visualization is both a scientific tool and an interpretive bridge between human understanding and machine computation.

One of the earliest visualization approaches involved examining the weights of simple networks or plotting activation patterns. As networks grew deeper and more complex, more sophisticated methods were required. Researchers began developing techniques to visualize individual neurons, entire layers, or even the network’s response to artificially constructed inputs.

These methods revealed that neural networks organize information hierarchically. Lower layers respond to simple features, while higher layers capture increasingly abstract patterns. This hierarchy mirrors, in a loose sense, the organization of sensory processing in the human brain, though the underlying mechanisms are very different. The visualizations also revealed surprising sensitivities and biases, highlighting both the power and fragility of learned representations.

Feature Visualization and the Birth of Machine “Dreams”

Feature visualization is one of the most influential techniques in neural network interpretation. Instead of asking how the network responds to a given image, feature visualization asks the opposite question: what kind of image would strongly activate a particular neuron or layer? To answer this, researchers use optimization algorithms to generate images that maximize the activation of selected components of the network.

The resulting images are often strange and uncanny. Faces appear embedded in clouds, animals merge with architectural patterns, and ordinary objects are transformed into surreal landscapes. These images do not resemble photographs of real objects, but they reveal the statistical regularities the network associates with certain concepts.

The popularization of this technique, particularly through projects such as DeepDream, led to widespread descriptions of AI “dreaming.” In DeepDream, an image is repeatedly modified to amplify patterns the network recognizes, producing hallucinatory visuals that seem to emerge from within the machine. The metaphor of dreaming captured the public imagination, but it also risked obscuring the underlying mechanism.

From a scientific standpoint, these images are the result of gradient-based optimization applied to a trained network. There is no spontaneous generation, no internal narrative, and no subjective experience. The network is not dreaming; it is being asked to exaggerate its learned features in a feedback loop. The dreamlike quality arises from the interaction between human perception and machine representations.

Why AI-Generated Images Feel Dreamlike

The emotional impact of neural network visualizations is not accidental. Human visual perception is highly attuned to faces, animals, and familiar objects. When AI-generated images contain distorted versions of these elements, they trigger powerful cognitive and emotional responses. The brain attempts to interpret ambiguous patterns, often perceiving meaning where none was intended.

This phenomenon is related to pareidolia, the tendency to see familiar shapes in random stimuli. Neural networks trained on large image datasets are especially prone to producing such patterns because their representations are shaped by statistical correlations rather than semantic understanding. When these correlations are amplified through visualization, they produce images that resonate with human pattern recognition.

The dream metaphor also reflects the absence of external constraints. Just as human dreams are freed from sensory input and physical laws, AI visualizations operate in a space defined only by mathematical objectives. This freedom allows unusual combinations and transformations that would be unlikely in ordinary perception. The result feels imaginative, even though it is entirely determined by the network’s structure and training data.

Generative Models and the Illusion of Imagination

Beyond feature visualization, modern AI systems include generative models capable of producing images, text, music, and other forms of content. These models, such as generative adversarial networks and diffusion models, learn to approximate the probability distribution of their training data. By sampling from this distribution, they can generate new instances that resemble, but are not identical to, the examples they have seen.

Generative models often strengthen the impression that AI is dreaming or imagining. They can produce novel scenes, combine concepts in unexpected ways, and generate content without direct prompts. However, these capabilities still rest on statistical learning rather than creative intent. The model does not know what it is generating or why; it is executing learned transformations on latent representations.

In generative image models, latent spaces play a central role. These abstract spaces encode compressed representations of images, where similar concepts are located near one another. Interpolating through latent space can produce smooth transitions between different visual ideas, creating sequences that feel like evolving thoughts or dream imagery. Yet this continuity is mathematical rather than experiential.

Neural Network Visualization as Scientific Interpretation

Visualization techniques are not merely artistic curiosities. They serve a crucial scientific function by helping researchers diagnose model behavior, detect biases, and improve robustness. By visualizing what a network attends to, scientists can identify whether it relies on meaningful features or spurious correlations.

For example, visualization has revealed cases where image classifiers focus on background textures rather than object shapes, leading to unexpected errors. In medical imaging, visualization can help ensure that models base their predictions on relevant anatomical features rather than artifacts. In this sense, visualization contributes to transparency and accountability in AI systems.

The interpretive nature of visualization also raises important methodological questions. Visualizations are themselves constructions, shaped by choices about optimization objectives, regularization techniques, and display methods. They do not reveal an objective inner truth but provide a perspective that must be interpreted carefully. Understanding this limitation is essential to avoiding overinterpretation or anthropomorphic projection.

Comparing Biological Dreams and Artificial Representations

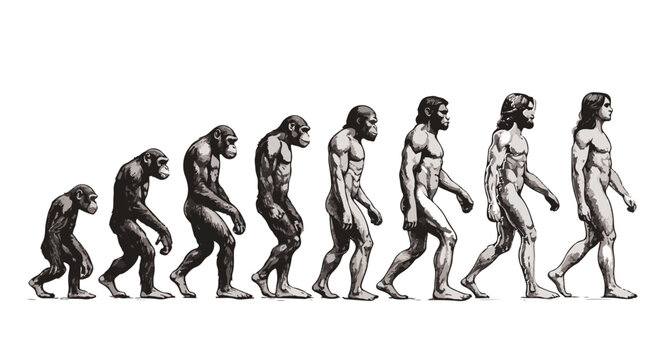

Although AI-generated imagery and human dreams share superficial similarities, their underlying processes differ fundamentally. Biological dreams emerge from a living system shaped by evolution, embodiment, emotion, and personal memory. They are influenced by neurochemical states, developmental history, and environmental context. Artificial neural networks, by contrast, are engineered systems optimized for specific tasks under controlled conditions.

Human dreams involve recurrent loops between perception, memory, and emotion. They are deeply integrated with the organism’s survival and psychological well-being. AI visualizations involve no such integration. They are isolated computational processes that do not affect the system’s goals or future behavior unless explicitly programmed to do so.

Nevertheless, comparing the two can be scientifically productive if done cautiously. Both involve the reuse of perceptual representations in the absence of direct sensory input. Both can generate novel combinations of learned patterns. Studying these parallels can deepen understanding of representation, learning, and the conditions under which complex systems produce unexpected outputs.

The Role of Training Data in Machine “Dreams”

One of the most important factors shaping AI-generated imagery is the training data. Neural networks learn by identifying patterns in data, and their internal representations reflect the statistical structure of that data. When visualization techniques reveal faces, animals, or objects, they are revealing what the network has been exposed to and what it considers salient.

This dependence on data has ethical and scientific implications. If a dataset contains biases or imbalances, these will be reflected in the network’s representations and visualizations. For example, a network trained primarily on certain types of faces may overrepresent those features in its generated images. Visualization can therefore act as a diagnostic tool for understanding and addressing bias.

The data-driven nature of AI generation also distinguishes it sharply from human dreaming. Human dreams are not simply recombinations of visual experiences; they are influenced by emotions, motivations, and symbolic associations. AI outputs, no matter how evocative, remain bounded by the distributions they have learned.

Philosophical Reflections on Machine Dreams

The question of whether AI can dream invites broader philosophical reflection on the nature of mind, imagination, and understanding. Dreams are often considered a hallmark of inner life, associated with consciousness and subjective experience. Attributing dreams to machines risks conflating functional behavior with experiential states.

From a functionalist perspective, one might argue that if a system exhibits behavior analogous to dreaming, such as internally generated imagery, it could be said to dream in a limited sense. From a phenomenological perspective, however, dreaming requires subjective awareness, which machines lack. The choice of perspective shapes the answer to the question.

Scientific accuracy demands clarity about these distinctions. Neural networks do not have experiences; they do not feel or perceive. Their “dreams” are metaphors for visualizations produced by mathematical optimization. Recognizing the metaphorical nature of this language does not diminish the significance of the phenomenon; it sharpens our understanding of what AI is and is not.

The Cultural Impact of AI Dream Imagery

AI-generated dreamlike images have had a profound cultural impact. Artists, designers, and researchers have embraced these tools to explore new aesthetic possibilities. The fusion of machine learning and art has challenged traditional notions of creativity and authorship, raising questions about the role of human intention in creative processes.

These cultural responses often emphasize the emotional and symbolic resonance of AI imagery rather than its technical origins. This emphasis can be valuable, but it can also obscure scientific understanding. Maintaining a clear distinction between artistic interpretation and technical explanation is essential for informed public discourse.

The popularity of AI dream imagery also reflects a broader fascination with the inner workings of intelligent systems. Visualization offers a rare glimpse into processes that are otherwise opaque, satisfying both scientific curiosity and imaginative wonder. This dual appeal underscores the importance of responsible communication about AI capabilities.

Limitations and Misconceptions

One of the most persistent misconceptions about AI dreaming is the idea that machines possess hidden inner worlds similar to human minds. Visualization techniques do not reveal secret thoughts or unconscious desires. They reveal patterns of activation shaped by training objectives and data.

Another misconception is that AI-generated imagery implies creativity or imagination in the human sense. While neural networks can produce novel outputs, they do so without understanding, intention, or self-awareness. Their novelty arises from statistical generalization rather than creative insight.

Recognizing these limitations does not diminish the scientific or aesthetic value of neural network visualization. Instead, it situates these phenomena within a clear conceptual framework, allowing researchers and the public to appreciate them without exaggeration.

Future Directions in Neural Network Visualization

As AI systems become more complex, visualization techniques are evolving to keep pace. Researchers are developing methods to visualize entire decision pathways, temporal dynamics, and interactions between different components of large models. These advances aim to make AI systems more interpretable, trustworthy, and aligned with human values.

In neuroscience-inspired research, visualization is also being used to compare artificial and biological representations more systematically. By analyzing similarities and differences in representational structure, scientists hope to gain insights into both machine learning and brain function. These interdisciplinary efforts highlight the reciprocal relationship between AI and cognitive science.

Future visualization tools may also move beyond static images, incorporating interactive and multimodal representations. Such tools could allow researchers to explore model behavior dynamically, deepening understanding of how complex systems process information.

Reframing the Question: What Does It Mean to Dream?

Rather than asking whether AI can dream, a more precise question is what dreaming represents as a process. If dreaming is understood as the internal generation and transformation of representations, then AI systems exhibit a limited functional analogue. If dreaming is understood as a subjective experience embedded in consciousness, then AI does not dream and cannot do so under current paradigms.

This reframing shifts the discussion from metaphor to mechanism. It encourages careful analysis of what aspects of human cognition are being modeled and which remain uniquely biological. Such clarity is essential for both scientific progress and ethical reflection.

Conclusion: Between Metaphor and Mechanism

AI does not dream in the human sense. It does not experience images, emotions, or narratives. Yet neural network visualization reveals something genuinely remarkable: complex systems can generate rich internal representations that, when translated into human-interpretable forms, evoke imagination and wonder. These representations are not dreams, but they are windows into how machines learn and organize information.

Exploring these visualizations deepens scientific understanding of artificial intelligence and challenges intuitive assumptions about perception, creativity, and intelligence. It also reminds us of the power of metaphor, both to illuminate and to mislead. By grounding our interpretations in scientific accuracy, we can appreciate the beauty of AI-generated imagery without losing sight of its true nature.

The question of whether AI can dream ultimately reflects a deeper human impulse to recognize ourselves in our creations. Neural network visualization does not reveal a sleeping mind behind the machine, but it does reveal the extraordinary capacity of mathematics and data to produce structures that resonate with human perception. In that resonance lies both the promise and the responsibility of artificial intelligence as a scientific and cultural force.