Imagine waking up each day with a heavy fog blanketing your mind and heart. The simplest joys — the warmth of sunlight, the laughter of a loved one, the satisfaction of a completed task — all seem muted, distant, or outright unreachable. This is the reality for millions worldwide who suffer from depression, a complex emotional and biological illness that goes far beyond occasional sadness.

Depression is not a failure of will or a mere passing phase of gloom. It is a profound disruption in brain chemistry and function that changes how a person thinks, feels, and interacts with the world. Those who endure it often describe it as a loss of self, a disconnect from hope and vitality. It can isolate, paralyze, and, tragically, lead some to contemplate or commit suicide.

Yet, amid this darkness, modern science has developed tools to help. Antidepressants—medications designed to restore balance to the brain’s chemical symphony—offer hope. But how do these drugs work? What happens inside the brain when someone takes an antidepressant? Understanding this not only illuminates the biology of depression but also humanizes the experience, showing us that recovery is a complex, delicate, and deeply personal process.

The Brain’s Chemical Symphony: Neurotransmitters and Mood

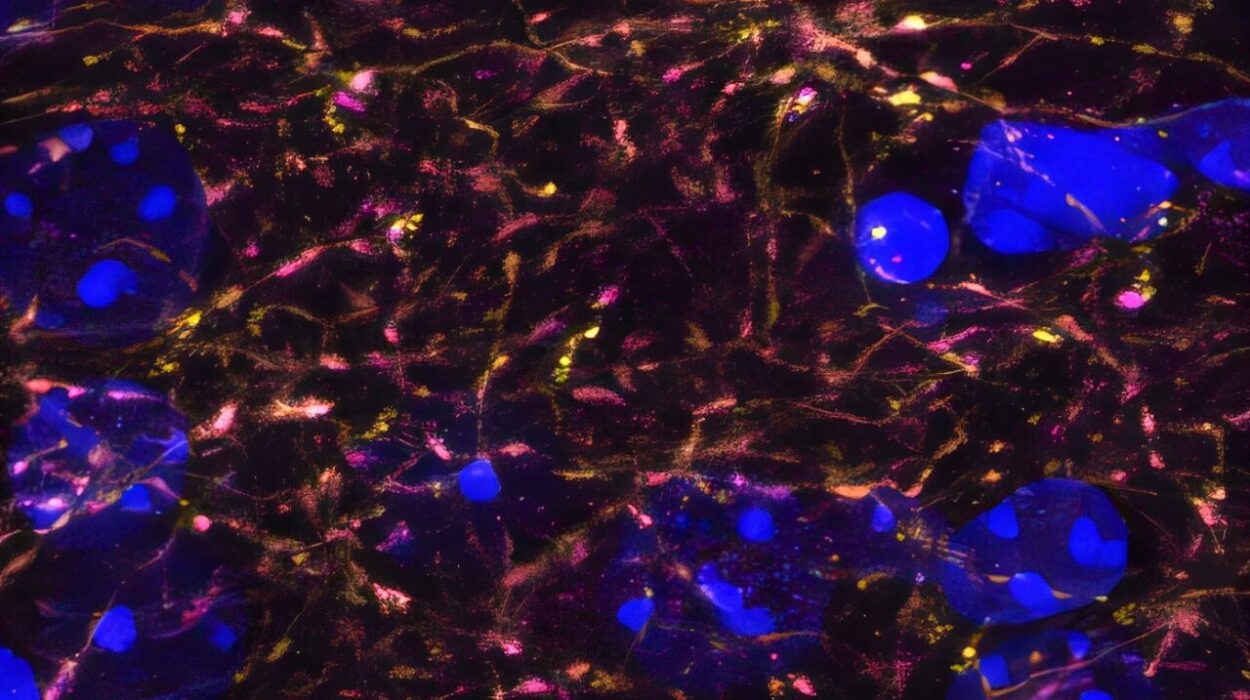

To grasp how antidepressants affect the brain, it’s essential first to understand the key players in our brain’s communication network: neurotransmitters. These are chemical messengers that neurons—the brain’s nerve cells—use to send signals to each other.

Among the hundreds of neurotransmitters, three stand out as central to mood regulation: serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. Imagine them as the conductors of an orchestra, each contributing unique notes and rhythms that together shape how we feel emotionally.

Serotonin, often dubbed the “feel-good” neurotransmitter, influences mood, anxiety, and happiness. Norepinephrine affects alertness and energy, while dopamine plays a critical role in motivation, reward, and pleasure. When the levels or activity of these chemicals are disrupted, the brain’s emotional harmony falters, leading to symptoms like persistent sadness, lack of energy, and loss of interest in life.

For decades, scientists hypothesized that depression stemmed from a “chemical imbalance” in these neurotransmitters. While this explanation is an oversimplification, it laid the groundwork for developing medications that could help restore balance.

The Birth of Antidepressants: From Chance Discovery to Purposeful Design

The journey of antidepressants began in the mid-20th century with a stroke of scientific serendipity. Originally developed for other conditions, the first antidepressant drugs were discovered almost accidentally.

In the 1950s, researchers noticed that a drug called iproniazid, initially used to treat tuberculosis, caused mood improvements in patients. Around the same time, another drug, imipramine, designed to treat schizophrenia, showed antidepressant effects. These discoveries opened the door to a new era of psychiatric medicine, focused on chemical modulation of the brain.

These early antidepressants, known as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), worked by increasing the levels of neurotransmitters in the brain, particularly serotonin and norepinephrine. However, they had significant side effects, including dietary restrictions and cardiovascular risks, limiting their use.

Modern Antidepressants: The Rise of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

The introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the late 1980s marked a revolution in depression treatment. Drugs like fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), and citalopram (Celexa) specifically target serotonin, the neurotransmitter deeply linked to mood regulation.

But what does “selective serotonin reuptake inhibition” actually mean? Neurons release serotonin into the tiny gaps between cells called synapses, where it binds to receptors on the receiving neuron to transmit signals. Afterward, serotonin is typically reabsorbed by the sending neuron in a process called reuptake. SSRIs block this reuptake, allowing serotonin to remain longer in the synapse, thus enhancing its mood-boosting effects.

This targeted approach made SSRIs safer and more tolerable than their predecessors, vastly expanding access to treatment. However, the story is far more complex than simply boosting serotonin levels.

The Brain’s Adaptation: Why Antidepressants Take Time to Work

One of the most perplexing experiences for people starting antidepressants is the delay before feeling relief. Unlike painkillers that often work quickly, antidepressants typically require weeks to manifest noticeable effects. This delay puzzled scientists for decades.

The answer lies in the brain’s remarkable ability to adapt. When serotonin levels are elevated due to SSRIs, the brain doesn’t instantly translate this into improved mood. Instead, a cascade of downstream changes occurs.

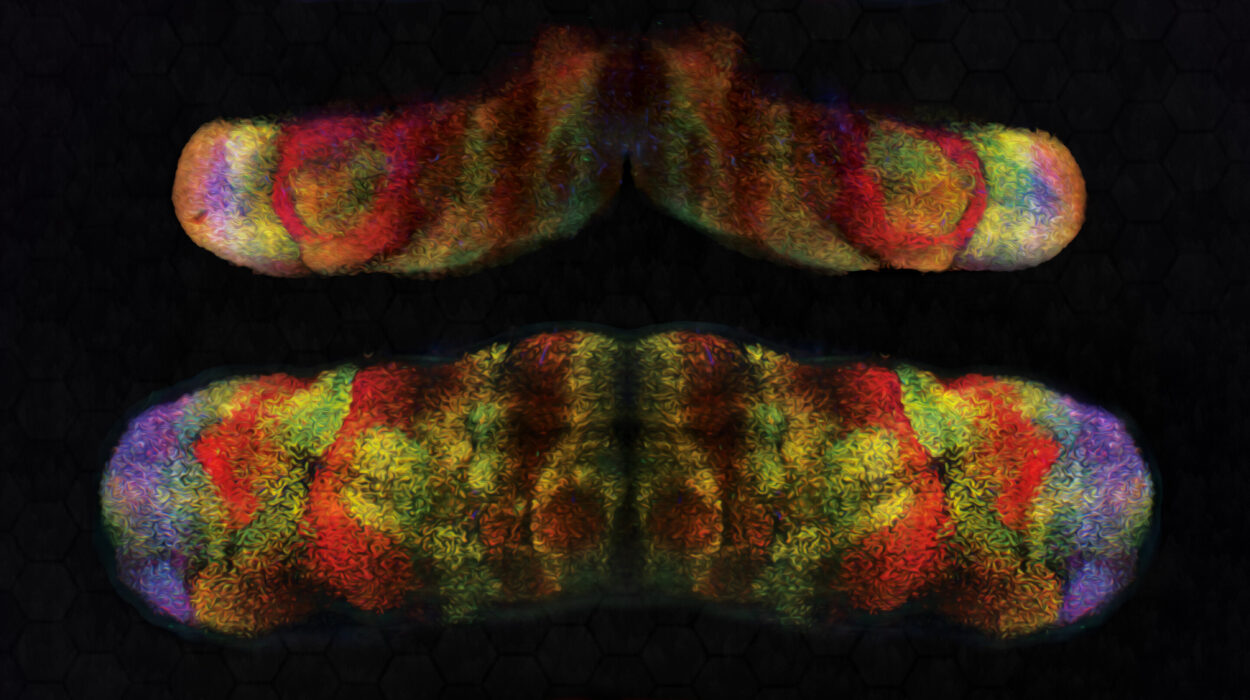

These include alterations in receptor sensitivity, the growth of new neural connections, and modulation of other neurotransmitter systems. For example, research has shown that antidepressants promote neurogenesis—the birth of new neurons—in the hippocampus, a brain region involved in memory and emotion that is often shrunken in people with depression.

These neuroplastic changes gradually restore the brain’s capacity for emotional regulation and resilience, explaining why treatment effects unfold over weeks.

Beyond Serotonin: Other Classes of Antidepressants and Their Mechanisms

While SSRIs remain the most widely prescribed antidepressants, other drug classes target different aspects of brain chemistry.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) increase both serotonin and norepinephrine, potentially addressing symptoms like fatigue and low energy more effectively. Examples include venlafaxine and duloxetine.

Tricyclic antidepressants, though less common today, affect multiple neurotransmitters and have proven effective in treatment-resistant depression.

Another group, atypical antidepressants, includes medications like bupropion, which primarily enhances dopamine and norepinephrine activity, useful for patients with fatigue or lack of motivation.

Each medication interacts with the brain’s chemistry uniquely, highlighting that depression is not a one-size-fits-all condition but a diverse disorder requiring personalized approaches.

The Role of the Brain’s Stress System: Antidepressants and Cortisol

Depression is often linked with chronic stress, which triggers overactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis—the body’s central stress response system. This leads to elevated cortisol levels, a hormone that, in excess, can damage brain structures like the hippocampus.

Interestingly, antidepressants appear to normalize HPA axis function, reducing cortisol secretion and protecting the brain from stress-related damage. This mechanism may contribute to mood improvements and cognitive restoration during treatment.

Understanding this interaction underscores that antidepressants do more than tweak neurotransmitters; they also recalibrate the brain’s stress systems, helping to heal deeper biological wounds.

The Emotional Side of Antidepressants: Hope, Fear, and the Healing Journey

For those struggling with depression, starting antidepressants can evoke a complex mixture of emotions. Hope flickers—the possibility of regaining a life once lost—but so does fear and uncertainty about side effects, stigma, and the unknowns of treatment.

Side effects vary widely, from nausea and headaches to sexual dysfunction and emotional blunting. For some, these are minor inconveniences; for others, they can be deeply distressing.

Moreover, antidepressants do not erase pain overnight or cure underlying life difficulties. Instead, they provide the brain with the chemical foundation to rebuild emotional resilience, often in conjunction with psychotherapy, lifestyle changes, and social support.

The healing process is rarely linear. Setbacks, frustrations, and doubts may arise, but for many, antidepressants open a door back to themselves—a door that depression had closed.

The Controversies and Challenges Surrounding Antidepressants

Despite their widespread use, antidepressants remain controversial. Critics argue that the “chemical imbalance” theory oversimplifies depression’s complexity, and that medications may be overprescribed or used as a quick fix.

Studies also reveal that antidepressants may be less effective in mild to moderate depression, where psychotherapy alone might suffice. Additionally, some patients experience treatment resistance, requiring multiple trials or combinations of drugs.

There is also concern about withdrawal symptoms when stopping antidepressants, sometimes called “discontinuation syndrome,” which can mimic relapse and complicate long-term treatment.

These challenges highlight the necessity of personalized medicine and open, informed conversations between patients and clinicians.

The Future of Antidepressant Therapy: New Frontiers in Brain Science

Recent advances offer hope for more effective, faster-acting treatments. Ketamine, traditionally an anesthetic, has shown rapid antidepressant effects by targeting glutamate, a neurotransmitter involved in brain plasticity.

Other novel approaches include psychedelic-assisted therapy, using substances like psilocybin to “reset” brain networks and enhance emotional processing in a controlled therapeutic environment.

Genetic research is beginning to unravel why individuals respond differently to antidepressants, paving the way for tailored treatments based on genetic profiles.

Brain imaging and biomarkers are also being studied to better predict treatment response and monitor progress, moving psychiatry toward a more precise and compassionate practice.

The Human Story: Living with Depression and Antidepressants

Behind the science are millions of individual stories — people navigating the turbulent seas of depression, sometimes finding safe harbor through medication.

For many, antidepressants are not a magic bullet but a lifeline. They restore the ability to get out of bed, to connect, to dream again. They enable patients to engage with therapy, rebuild relationships, and reclaim purpose.

But the journey is deeply personal, requiring patience, courage, and often, a willingness to confront both inner demons and societal stigma.

Hearing these stories reminds us that depression is not a weakness or a choice but a complex brain disorder—and that treatment is a beacon of hope grounded in compassion and understanding.