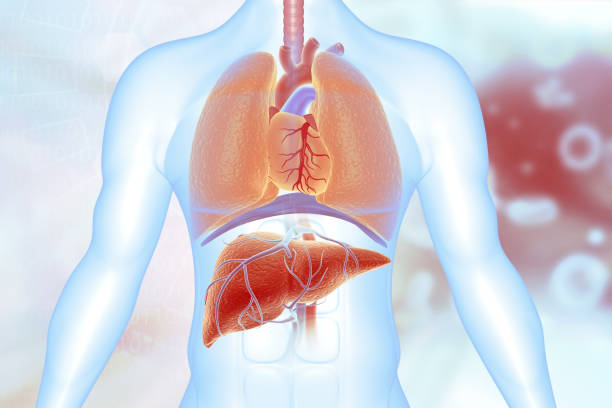

Hepatitis is a word that carries both fear and mystery. It comes from the Greek hepar, meaning “liver,” and -itis, meaning “inflammation.” At its core, hepatitis is inflammation of one of the body’s most vital organs—the liver. But it is far more than a biological term. It is a global health concern, a human story of resilience and struggle, and a reminder of how fragile and yet powerful the human body can be.

The liver, often called the body’s chemical factory, performs more than 500 functions: detoxifying harmful substances, producing bile for digestion, storing energy, and helping regulate metabolism. When the liver is inflamed or injured, every aspect of health suffers. Hepatitis, then, is not simply a disease of the liver; it is a disruption to the entire orchestra of human physiology.

Yet hepatitis is not one disease but many, caused by different agents, behaviors, and conditions. Some forms are fleeting and mild, while others silently progress for decades, leading to cirrhosis, liver failure, or cancer. To understand hepatitis is to explore a story of viruses, toxins, immunity, and human choices—a story that is deeply scientific but also profoundly human.

Understanding Hepatitis: More Than One Cause

At its most basic level, hepatitis refers to inflammation of the liver. But what sparks that inflammation can vary dramatically. The most common culprits are viruses, giving rise to hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. Each of these viruses has its own method of transmission, risk factors, and consequences.

But viruses are not the only causes. Alcohol, medications, toxins, autoimmune conditions, and even metabolic disorders can set the liver ablaze. In each case, the body’s response to injury leads to swelling, cellular stress, and sometimes irreversible scarring.

So when we speak of hepatitis, we are speaking of a family of conditions united by liver inflammation but divided by origins. Understanding these origins is the first step in unraveling the mystery of hepatitis.

Viral Hepatitis: Five Letters, Five Stories

Hepatitis A: The Traveler’s Companion

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is often called the “traveler’s hepatitis,” because it spreads through contaminated food and water. In many parts of the world with poor sanitation, hepatitis A is almost unavoidable in childhood. While its symptoms can be uncomfortable—fatigue, jaundice, stomach upset—it rarely causes long-term damage.

For most people, hepatitis A is an acute infection: the immune system clears it within weeks, leaving behind lifelong immunity. Vaccination has made hepatitis A preventable in many countries, turning a once-common disease into a declining threat.

Hepatitis B: The Stealthy Opponent

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is one of the most formidable forms of hepatitis. Spread through blood, sexual contact, or from mother to child during birth, it affects more than 250 million people worldwide. Unlike hepatitis A, HBV can become chronic, silently damaging the liver for decades before complications arise.

Chronic hepatitis B is a leading cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer). But it is also preventable: a safe and effective vaccine has been available since the 1980s. Antiviral therapies can suppress the virus, giving millions a chance at a healthier life. Yet, stigma, lack of awareness, and unequal access to healthcare continue to make HBV a pressing global issue.

Hepatitis C: The Quiet Intruder

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) spreads primarily through blood-to-blood contact—once associated heavily with transfusions, now more with injection drug use. Unlike HBV, there is no vaccine for hepatitis C. But the story of HCV is also one of triumph: in the last decade, direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have transformed treatment. What was once considered incurable can now often be eradicated with a simple course of pills.

Still, many live with HCV unknowingly. Because the virus often causes no symptoms until severe liver damage occurs, millions remain undiagnosed. The challenge today is not only medical but also social: identifying and reaching those most at risk.

Hepatitis D: The Dependent Virus

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is unusual—it cannot infect on its own but requires the presence of hepatitis B. In those already infected with HBV, hepatitis D can accelerate disease progression, leading to severe complications. Vaccination against HBV is, therefore, also protection against HDV, highlighting the interconnectedness of these infections.

Hepatitis E: The Overlooked Threat

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) resembles hepatitis A in that it spreads through contaminated water and food, especially in areas with poor sanitation. In most cases, it causes acute illness and resolves spontaneously. But in pregnant women, hepatitis E can be particularly dangerous, sometimes leading to life-threatening complications.

Non-Viral Causes of Hepatitis

Alcoholic Hepatitis: Poison from Within

Alcohol has long been woven into human culture, yet excessive consumption can devastate the liver. Alcoholic hepatitis is a result of chronic heavy drinking, where liver cells become damaged and inflamed. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, jaundice, and fever. If drinking continues, the condition can progress to cirrhosis and liver failure.

Drug-Induced Hepatitis: A Double-Edged Sword

Many medications that save lives can also harm the liver. Acetaminophen (paracetamol), when taken in excess, is one of the leading causes of acute liver failure worldwide. Other drugs, including some antibiotics, statins, and chemotherapy agents, may also trigger hepatitis in sensitive individuals.

Autoimmune Hepatitis: When the Body Turns on Itself

In autoimmune hepatitis, the immune system mistakenly attacks the liver, leading to chronic inflammation. This condition is not caused by viruses or toxins but by an internal misfire of immunity. If left untreated, autoimmune hepatitis can cause cirrhosis and liver failure. However, with early diagnosis and immunosuppressive therapy, many patients can live long, healthy lives.

Metabolic and Genetic Causes

Certain genetic conditions, such as Wilson’s disease (copper accumulation) or hemochromatosis (iron overload), can inflame and damage the liver. These metabolic disorders are rarer but illustrate how diverse the origins of hepatitis can be.

The Symptoms of Hepatitis

Hepatitis does not always announce itself with dramatic signs. Many people may feel healthy while their liver quietly deteriorates. When symptoms do appear, they often overlap regardless of the cause.

- Fatigue: A deep, unshakable tiredness is one of the earliest signs.

- Jaundice: Yellowing of the skin and eyes due to bilirubin buildup.

- Abdominal pain: Especially in the upper right side, where the liver sits.

- Dark urine and pale stools: Reflecting disruptions in bile processing.

- Loss of appetite, nausea, or vomiting: The liver’s struggle affects digestion.

- Fever and joint pain: Sometimes present, particularly in viral hepatitis.

In chronic hepatitis, symptoms may remain silent until advanced stages, when scarring (cirrhosis) or cancer develops. This silence is what makes hepatitis so dangerous—people may not know they are infected until irreversible damage has occurred.

Diagnosis: Unmasking the Hidden Disease

Diagnosing hepatitis requires careful investigation, as symptoms alone are not definitive. Physicians rely on a combination of medical history, blood tests, imaging, and sometimes biopsies.

- Blood tests: These measure liver enzymes (ALT, AST), bilirubin levels, and markers of viral infection (antibodies, viral DNA/RNA). Elevated liver enzymes are often the first clue.

- Viral markers: Specific tests distinguish between hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. For example, HBsAg indicates active hepatitis B infection, while anti-HCV antibodies point to exposure to hepatitis C.

- Imaging: Ultrasound, CT, or MRI scans assess the liver’s structure, looking for fibrosis, fatty changes, or tumors.

- Liver biopsy: In some cases, a small tissue sample is taken to assess the extent of inflammation and scarring.

Modern diagnostics have advanced to include non-invasive tests such as transient elastography (FibroScan), which measures liver stiffness to detect fibrosis without the need for biopsy.

Treatment: Fighting Back Against Hepatitis

Treatment depends on the cause, and here lies one of the most hopeful parts of the hepatitis story. While once thought untreatable, many forms of hepatitis are now manageable—or even curable.

Viral Hepatitis Treatments

- Hepatitis A and E: No specific antiviral therapy exists. Supportive care, hydration, and rest are usually sufficient. Vaccines are available for hepatitis A and, in some regions, for hepatitis E.

- Hepatitis B: Antiviral drugs such as tenofovir and entecavir suppress viral replication, reducing the risk of liver damage. While not a cure, they allow patients to live long, healthy lives. Vaccination remains the most powerful prevention.

- Hepatitis C: Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have revolutionized treatment, curing over 95% of patients with minimal side effects. What was once a lifelong burden can now be eliminated in weeks.

- Hepatitis D: Treatment is challenging, but antiviral therapies and emerging drugs such as bulevirtide offer hope. Prevention through HBV vaccination is crucial.

Non-Viral Hepatitis Treatments

- Alcoholic hepatitis: The cornerstone is alcohol cessation, supported by counseling and, in severe cases, corticosteroids or liver transplantation.

- Drug-induced hepatitis: Stopping the offending medication usually leads to recovery. In cases of acetaminophen overdose, N-acetylcysteine is a lifesaving antidote.

- Autoimmune hepatitis: Immunosuppressive drugs, such as corticosteroids and azathioprine, help control inflammation and prevent progression.

- Metabolic disorders: Treatments vary—chelation therapy for Wilson’s disease, phlebotomy for hemochromatosis—but early detection is key.

Complications: When Hepatitis Progresses

If untreated, hepatitis can lead to severe complications. Chronic inflammation may cause fibrosis—scar tissue that gradually replaces healthy liver cells. Extensive fibrosis is called cirrhosis, which disrupts the liver’s architecture and function.

Cirrhosis brings its own set of dangers: ascites (fluid buildup in the abdomen), variceal bleeding, encephalopathy (confusion due to toxin buildup), and, most gravely, hepatocellular carcinoma. These complications are often irreversible, underscoring the importance of early diagnosis and treatment.

Prevention: Stopping Hepatitis Before It Starts

Preventing hepatitis is one of medicine’s greatest success stories. Vaccines for hepatitis A and B have saved millions of lives. Safe food and water practices reduce the risk of hepatitis A and E. Harm reduction strategies—like clean needle programs and safe blood transfusion protocols—help control hepatitis B and C.

Equally important is education: understanding transmission routes, combating stigma, and encouraging testing. Hepatitis thrives in silence; breaking that silence is a powerful tool in prevention.

The Human Side of Hepatitis

Behind every statistic is a human story—a child born with HBV, an adult discovering HCV decades after a transfusion, a family torn by alcoholism and liver disease. These stories remind us that hepatitis is not only a biological phenomenon but also a deeply social one. Poverty, stigma, and lack of healthcare access shape the hepatitis epidemic as much as the viruses themselves.

The Future: Toward Elimination

The World Health Organization has set an ambitious goal: to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030. This vision rests on three pillars: prevention, testing, and treatment. With vaccines, curative drugs, and global cooperation, it is achievable.

But challenges remain: reaching marginalized communities, addressing stigma, and ensuring equitable access to therapies. The future of hepatitis is not only a medical challenge but also a moral one—do we, as a global society, have the will to protect every life from this preventable and treatable condition?

Conclusion: Healing the Silent Organ

Hepatitis is more than inflammation of the liver—it is a test of our collective resilience, compassion, and scientific progress. It challenges us to protect the silent organ that sustains life, to prevent suffering where we can, and to heal with both medicine and humanity where suffering exists.

The liver is remarkably resilient—it can regenerate, repair, and recover even after significant damage. So too can humanity. With knowledge, compassion, and action, hepatitis does not have to be a silent killer. It can be a story of healing, survival, and hope.