To step into the world of ancient Greece is to enter a realm where myth and reality intertwine, where the divine was not distant but present in every stone, every grove, and every flame that flickered on the altar. Greek religion was not simply a system of beliefs or a collection of sacred stories; it was a way of life that shaped politics, art, festivals, and even the rhythms of daily existence. The Greeks lived in a cosmos they believed to be animated by gods, spirits, and sacred forces, and their rituals and temples stood as bridges between the mortal and the divine.

When we speak of Greek religion, we speak not only of the mighty Olympians—Zeus, Hera, Athena, Apollo, and their kin—but also of a vast pantheon of local gods, spirits of rivers and mountains, protective household deities, and heroes whose cults blurred the line between mortals and immortals. This was a religion deeply communal, where worship was less about private salvation and more about honoring the gods to secure harmony, fertility, protection, and prosperity for the whole community.

At its core, Greek religion was an ever-living dialogue between human beings and the divine. It expressed itself in myth, ritual, and architecture—in stories that explained the origins of the world, in sacrifices that bound gods and mortals in reciprocal exchange, and in temples whose marble columns still stand as silent witnesses to humanity’s quest for transcendence.

The Gods of Olympus

Greek religion is inseparable from its gods. To the Greeks, the gods were not abstract forces but beings with personalities, passions, and powers. They quarreled, loved, punished, and rewarded. They were immortal yet strikingly human, reflecting the joys and sorrows of mortal existence in divine form.

Zeus: The King of Gods

Zeus, the thunder-wielding father of gods and men, reigned supreme over Mount Olympus. He was the protector of order, hospitality, and justice. Yet he was also known for his many affairs, fathering gods, heroes, and demigods who populated Greek mythology. To pray to Zeus was to seek balance and authority in a world prone to chaos.

Hera: The Queen of Heaven

Hera, Zeus’s wife and sister, embodied the dignity of queenship and the sanctity of marriage. Fierce in her protection of marital bonds, she was also remembered for her jealousy toward Zeus’s many lovers and their offspring. Her presence reveals the Greek recognition of both the blessings and the tensions inherent in family and society.

Athena: Goddess of Wisdom

Born from the head of Zeus, fully armed and radiant, Athena represented wisdom, strategy, and civic responsibility. Unlike Ares, the god of war’s chaos, Athena was the goddess of just and strategic warfare. She was also a patroness of crafts and cities, most famously Athens, where the Parthenon rose in her honor.

Apollo and Artemis: The Divine Twins

Apollo embodied harmony, music, prophecy, and the pursuit of reason. His oracle at Delphi was among the most important religious sites in Greece, where mortals sought divine guidance. Artemis, his twin sister, was a huntress and guardian of wild creatures, representing independence and the cycles of nature.

Poseidon, Demeter, and the Earthly Forces

Poseidon, with his trident, ruled the sea and caused earthquakes, embodying the unpredictability of nature. Demeter, goddess of agriculture, symbolized the fertility of the earth and the cycles of sowing and harvest. Her grief for her daughter Persephone’s descent into the underworld gave rise to one of the most profound religious traditions: the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Dionysus: The God of Ecstasy

Among the most intriguing deities was Dionysus, god of wine, theatre, and ecstatic transformation. Worship of Dionysus often broke societal boundaries, blending joy with madness, reason with irrationality. His cult, filled with dramatic rituals, spoke to the human yearning for release, transformation, and communion with forces beyond control.

The pantheon of Greek gods was vast and diverse, extending far beyond Olympus. Every region, city, and household honored specific deities, and each god carried many local identities and epithets. This flexibility gave Greek religion a rich texture, constantly evolving yet rooted in a shared sense of divine presence.

Temples: Houses of the Divine

If the gods were everywhere, temples were their earthly homes. Rising in gleaming stone, often placed on acropolises or sacred groves, temples were not simply places of worship but monumental embodiments of devotion.

Architecture and Symbolism

Greek temples followed harmonious proportions, reflecting the belief that beauty, symmetry, and order pleased the gods. Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian styles each carried their distinct elegance, shaping the skyline of ancient cities. The Parthenon in Athens, dedicated to Athena, is perhaps the most iconic, its marble columns capturing both power and grace.

Temples were not places for congregational worship like modern churches but sanctuaries housing the divine image of the god. Worshippers gathered outside, in the open air, before altars where sacrifices were made. The temple itself was both a residence for the deity’s statue and a treasury, where offerings of gold, silver, and votive gifts were stored.

Sacred Spaces

Beyond temples, sacred spaces included groves, springs, and caves imbued with spiritual significance. The Oracle of Delphi, where Apollo spoke through the priestess Pythia, was set in a dramatic landscape, reminding visitors that nature itself was a medium of the divine. Olympia, with its temple to Zeus and its athletic games, united the Greek world in celebration of religious and cultural identity.

Each temple and sacred site was a focal point of communal identity. To build a temple was to affirm a city’s devotion, pride, and connection to the gods. These architectural masterpieces were acts of faith written in stone, embodying the belief that the divine walked among humans.

Rituals: Bridging the Human and Divine

Ritual was the beating heart of Greek religion, a living dialogue between mortals and gods. Through rituals, the Greeks honored the gods, sought their favor, and reaffirmed their communal bonds.

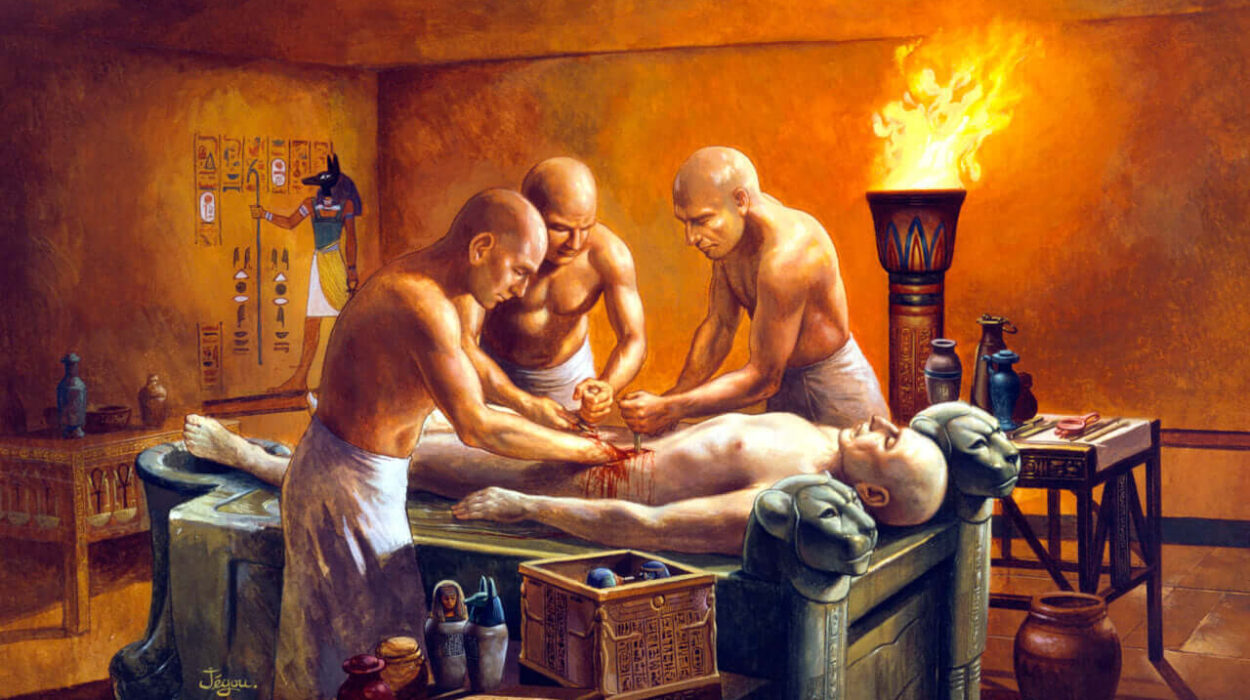

Sacrifice and Offering

The central act of Greek worship was sacrifice. Animals—often oxen, goats, or sheep—were ritually killed, their blood offered to the gods, and their meat shared in a communal feast. This act symbolized reciprocity: mortals gave to the gods in hopes of receiving blessings in return.

Libations—pourings of wine, oil, or honey—were also common, small yet meaningful gestures of devotion. Votive offerings, ranging from clay figurines to elaborate works of art, were left at sanctuaries as tokens of gratitude or petitions.

Festivals and Celebrations

Greek religious life was punctuated by festivals, grand occasions that combined ritual, feasting, athletic contests, theatre, and processions. The Panathenaic Festival in Athens celebrated Athena with sacrifices, music, and games. The Olympic Games, held at Olympia, honored Zeus and brought together city-states in peaceful competition.

Festivals were not only religious but also social and political events. They reinforced communal identity, celebrated cultural values, and provided moments of joy and unity. Through ritual drama and performance, such as the tragedies performed during the Dionysia, Greeks reflected on human suffering, divine justice, and the fragile line between order and chaos.

Mystery Cults and the Quest for Meaning

While most rituals were public and communal, Greek religion also embraced mystery cults—secret initiations offering deeper spiritual experiences. The Eleusinian Mysteries, dedicated to Demeter and Persephone, promised initiates insights into the afterlife and the renewal of life through death and rebirth. The cult of Dionysus invited participants into ecstatic rituals that dissolved boundaries and connected them to divine forces.

These mystery religions reveal the diversity of Greek spirituality, ranging from civic rituals that bound communities to personal quests for transcendence and eternal meaning.

Heroes and the Cult of the Dead

Greek religion extended beyond the gods to include heroes—mortal figures elevated to divine status after death. Heroes such as Heracles, Achilles, and Theseus were honored with shrines and sacrifices. They were seen as powerful intermediaries who could protect cities, grant strength, and inspire courage.

Ancestor worship and funerary rituals also formed an essential part of Greek religion. To honor the dead was to maintain bonds between generations and to ensure the continued favor of spirits. In this way, religion embraced both the divine and the human, the eternal and the mortal.

Philosophy and the Challenge of Religion

Greek religion did not exist in a vacuum; it evolved alongside philosophy. Thinkers such as Xenophanes, Plato, and Aristotle questioned traditional myths, sometimes criticizing the gods’ anthropomorphic flaws. Yet even philosophy could not entirely escape the influence of religion. Plato envisioned a divine order, and Aristotle saw a prime mover behind the cosmos.

This interplay between myth, ritual, and philosophy gave Greek culture its unique richness—a society both deeply religious and deeply rational, seeking truth in many forms.

Legacy of Greek Religion

Though ancient Greek religion eventually gave way to Christianity in the Roman Empire, its legacy endures. The myths of the gods continue to inspire art, literature, and psychology. Temples like the Parthenon still awe visitors with their beauty. The Olympic Games, revived in modern times, trace their roots to ancient religious festivals.

More profoundly, Greek religion reveals the human longing for connection—with nature, with community, with something greater than ourselves. It shows us that religion is not merely belief but lived experience: shared meals, sacred stories, and acts of devotion that wove meaning into daily life.

Conclusion: A World Alive with the Divine

Greek religion was a tapestry woven from gods, temples, and rituals, each thread shimmering with meaning. It was a world where the divine walked alongside mortals, where myths gave voice to eternal truths, and where rituals bound communities in joy, reverence, and remembrance.

To study Greek religion is to step into the heart of human imagination and faith. It reminds us that religion is not only about distant heavens but about the earth beneath our feet, the festivals we share, the stories we tell, and the temples we raise in stone and memory.

The gods of Greece may no longer receive sacrifices, but they live on—in the ruins that still touch the sky, in the myths that continue to inspire, and in the enduring human desire to bridge the mortal and the divine.