In the space beneath your fingernail, on the surface of a kitchen sponge, and even drifting through the quiet air of a hospital hallway, there exists a universe so vast and vibrant that it outnumbers the stars. This world is invisible to the naked eye, yet it shapes every aspect of our existence. It is ancient, it is everywhere, and it is alive.

Welcome to the microbial world—a domain ruled by entities so small that millions can live on the head of a pin. Germs, bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms make up this hidden empire. Though often feared, especially during pandemics or flu seasons, these microscopic life forms are not just agents of disease. They are creators, destroyers, symbionts, enemies, and sometimes, our closest allies.

To understand life, to understand ourselves, we must understand them.

The Word “Germ”: A Misunderstood Name

The word “germ” has become a synonym for danger. When someone sneezes, we worry about spreading germs. When we wash our hands, we aim to kill them. But scientifically speaking, “germ” is a catch-all term, not a precise label. It refers to any microscopic organism that can cause disease, but that includes several very different kinds of life—and even things that challenge our definition of “life” itself.

Viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi can all be called germs, but each is unique in its structure, behavior, and relationship with humans. Some are invaders. Others are neighbors. And many are essential for life on Earth.

By clumping them all into one dreaded category, we miss the beauty, complexity, and mystery of the microbial world. To really know germs, we must separate their identities and explore their lives.

The Bacterial Earth

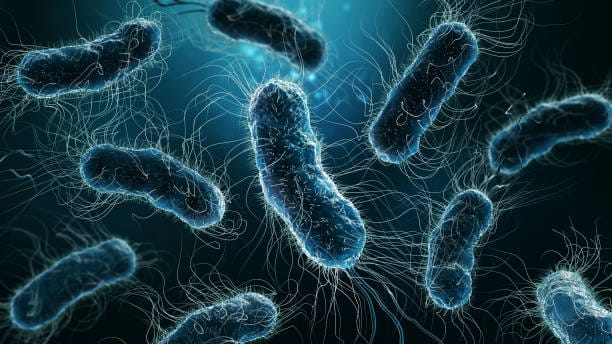

Long before humans, mammals, or even fish roamed the oceans, bacteria were here. They are the most ancient form of life on Earth, with a fossil record that stretches back over 3.5 billion years. In a way, they are our ancestors.

Bacteria are single-celled organisms, often rod-shaped, spiral, or spherical, and they live in every environment imaginable. From boiling hydrothermal vents deep under the sea to the icy crusts of glaciers, bacteria not only survive but thrive. They live in our soil, our water, and in the very air we breathe. And more importantly, they live inside us.

The human body carries an estimated 30 to 40 trillion bacterial cells—roughly as many bacterial cells as human ones. Most of these live in the gut, where they help digest food, produce essential vitamins, train the immune system, and even influence our moods and behaviors. This inner ecosystem is known as the microbiome, and it is as vital to health as any organ.

Yet not all bacteria are friendly. Some are opportunists, waiting for a wound, a weak immune system, or a lapse in hygiene. Others are aggressive pathogens, evolved to breach our defenses and hijack our cells. Bacteria like Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Yersinia pestis—the plague bacillus—have killed millions throughout history.

Still, the story of bacteria is not one of villains. It is one of diversity, adaptation, and resilience. They are neither good nor bad. They simply are. And they are everywhere.

Viruses: The In-Betweeners of Biology

Viruses are even smaller than bacteria—so small, in fact, that most cannot be seen even with a standard light microscope. But in their tiny shells lies one of the most powerful and mysterious forces in biology.

Unlike bacteria, viruses are not truly alive. They have no metabolism. They do not grow, eat, or reproduce on their own. Instead, they are genetic hitchhikers—particles of DNA or RNA wrapped in a protein coat. Alone, they are inert. But once inside a host cell, they come alive in the most astonishing way.

Viruses don’t just infect a cell. They take it over, turning it into a virus factory. The cell’s own machinery begins copying the viral genome, assembling viral particles, and eventually bursting open to release a new wave of infectious agents.

This ability to hijack life has made viruses some of the most feared microbes on the planet. Smallpox, polio, HIV, influenza, Ebola, and COVID-19—each was caused by a virus. And unlike bacteria, viruses are unaffected by antibiotics. Their simple structure makes them both hard to kill and easy to spread.

But not all viruses are enemies. Some integrate into our genome harmlessly. Others may protect us from bacterial infections. A growing body of research suggests that ancient viral DNA may have helped shape human evolution itself, influencing the development of the placenta and even the brain.

In fact, over eight percent of the human genome comes from viral remnants. We are, in a way, part virus ourselves.

The War and Peace Within Us

To the immune system, every microbe is a question. Is this friend or foe? Should it be welcomed, ignored, or destroyed?

From the moment we are born, our immune system begins this lifelong interrogation. It is a sophisticated defense network made of cells, proteins, and organs, constantly on the lookout for intruders. When a dangerous virus or bacterium enters the body, the immune response can be swift and violent—fever, inflammation, and the release of antibodies that target and destroy the invader.

But the immune system doesn’t just fight. It also learns. Once exposed to a pathogen, it remembers it. This memory allows for faster and stronger responses the next time, forming the basis of immunity. Vaccines take advantage of this by training the immune system in advance, using harmless pieces of a virus or bacteria to prepare the body for real threats.

Yet this system is not infallible. Sometimes it overreacts, attacking harmless substances like pollen or food (as in allergies), or even the body itself (as in autoimmune diseases). Sometimes it fails to recognize a pathogen or is overwhelmed by it.

Still, for most of us, the immune system is a quiet sentinel. Every breath, bite, or touch exposes us to countless microbes. And yet we remain upright, alive, and mostly unaware—thanks to this microscopic war that plays out inside us every day.

The Dance of Infection

An infection begins when a pathogen finds a way into the body. This can happen through a cut, a cough, a kiss, or a contaminated surface. But entry is only the first step. The microbe must then survive the body’s defenses, multiply, and spread.

Some bacteria secrete toxins that damage tissues. Others hide inside cells, shielded from immune attack. Viruses bind to specific receptors on cell surfaces, like keys fitting into locks, gaining access to their target tissues—lungs, liver, blood, or brain.

The symptoms of infection—fever, swelling, cough, pain—are not caused directly by the microbe, but by the body’s attempt to fight it off. In this way, illness is a side effect of battle.

Different microbes have different strategies. The influenza virus mutates rapidly, making it hard for the immune system to keep up. HIV targets the very cells meant to fight infection, crippling the immune response. Some bacteria form protective biofilms, communal structures that resist antibiotics and immune cells alike.

But the body has its own arsenal—natural killer cells, phagocytes, antimicrobial peptides, and more. And often, with or without help from medicine, it wins.

The Antibiotic Revolution—and Its Limits

When antibiotics were discovered in the 20th century, they transformed medicine. Infections that once killed by the millions—like strep throat, pneumonia, or syphilis—could now be cured. It was a miracle of modern science, and for a time, it seemed that humanity had triumphed over microbes.

But bacteria are ancient, clever survivors. Under pressure from antibiotics, they evolve. They mutate, share resistance genes, and adapt to new environments. Today, antibiotic resistance is one of the gravest threats to global health.

Superbugs—bacteria that resist multiple antibiotics—are on the rise. Infections that were once easy to treat are becoming deadly again. Overuse of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture has accelerated this crisis.

To combat it, scientists are searching for new drugs, alternative therapies, and better diagnostics. But the lesson is clear: we can’t outgun microbes forever. We must learn to coexist, to use antibiotics wisely, and to embrace a more nuanced view of the microbial world.

Viruses and the Pandemic Era

The COVID-19 pandemic reminded the world that microbes are not relics of history. They are present, potent, and capable of changing everything. A virus too small to see halted economies, overwhelmed hospitals, and reshaped daily life for billions.

But it also sparked unprecedented scientific collaboration. Vaccines were developed in record time. Genomes were sequenced, variants tracked, treatments tested. The pandemic showed us not just the danger of viruses, but the power of science, communication, and collective action.

Other viruses—old and new—still circulate. Ebola flares in Africa. Influenza evolves each year. Novel coronaviruses may emerge again. Living in a microbial world means being prepared, informed, and humble.

It means respecting the power of invisible life.

The Beneficial Microbial Majority

Despite their fearsome reputation, the vast majority of microbes are not harmful. In fact, they are essential.

Microbes fix nitrogen in soil, allowing plants to grow. They recycle nutrients, break down waste, and clean up oil spills. They help cows digest grass, termites eat wood, and humans absorb nutrients. They ferment yogurt, cheese, beer, and bread. They produce antibiotics, enzymes, and even biofuels.

In the human gut, bacteria outnumber our own cells and genes. This microbiome influences digestion, immunity, mood, and metabolism. Disruptions in the microbiome have been linked to obesity, diabetes, depression, and autoimmune disease. Fecal transplants—where healthy gut bacteria are transferred to sick patients—are now being used to treat certain infections and illnesses.

The more we learn about microbes, the more we see them not as enemies, but as partners in the story of life.

A Microscopic Universe Waiting to Be Understood

We are just beginning to scratch the surface of microbial diversity. It’s estimated that over 99% of microbial species remain undiscovered. The ocean, the soil, even the deep subsurface of Earth hold microbes we’ve never seen or studied.

With powerful new tools—like CRISPR gene editing, metagenomics, and advanced imaging—scientists are mapping this hidden universe. Each discovery brings new potential: for medicine, agriculture, climate change, and more.

The microbial world is not static. It evolves, adapts, and interacts with us in ways we are only beginning to grasp.

To understand it is to understand life itself.

Living in the Microbial Age

Every breath you take contains thousands of microbes. Every surface you touch, every bite you eat, carries microbial hitchhikers. But this is not a cause for fear—it’s a fact of life.

We are not separate from the microbial world. We are part of it.

The germs we fear and the bacteria we rely on are made of the same biological essence. Some harm us, some help us, and most ignore us completely. But together, they form a vast, ancient, and intricate web of life—one that underlies every breath, every heartbeat, and every moment on Earth.

To live in harmony with this world, we must respect its power, embrace its diversity, and remain curious about its secrets.

Because in the end, we are not alone—not even in our own bodies.

We are ecosystems. We are hosts. We are partners in the great microbial dance of life.