Entropy is one of the most profound and unsettling ideas ever discovered by science. It does not describe a force you can feel or a particle you can see. Instead, it reveals a deep tendency woven into the fabric of reality itself: the universe relentlessly moves from order toward disorder, from usable energy toward energy that can no longer do meaningful work. Entropy explains why hot things cool down, why engines are never perfectly efficient, why time seems to flow in only one direction, and why the universe, despite all its dazzling activity, is slowly running out of what physicists call “useful” energy.

At first glance, this claim sounds bleak, almost philosophical rather than scientific. How can the universe be “running out” of anything when energy is conserved? How can something as abstract as entropy dictate the ultimate fate of stars, galaxies, and life itself? To answer these questions, we must journey through thermodynamics, statistical physics, cosmology, and the human struggle to understand time. Along the way, entropy emerges not as a symbol of decay alone, but as a key to understanding why the universe looks the way it does, and why existence itself unfolds as a story rather than a static picture.

Energy Is Conserved, So What Is Being Lost?

One of the first principles students of physics learn is the law of conservation of energy. Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it can only change form. Chemical energy becomes heat, heat becomes motion, motion becomes electricity, and so on. At face value, this law seems to contradict the idea that the universe is running out of energy. If the total amount of energy always remains the same, how can there be an energy crisis on a cosmic scale?

The answer lies in the difference between energy in general and useful energy in particular. Not all energy is equally capable of doing work. A cup of hot coffee placed in a cold room contains energy that can, in principle, be harnessed. The same coffee after it has cooled to room temperature still contains energy, but that energy is now evenly distributed with its surroundings and cannot be used to perform work. The total energy has not changed, but its usefulness has.

Entropy is the concept that captures this distinction. It measures, in a precise physical sense, how spread out or degraded energy has become. As entropy increases, energy becomes more evenly distributed and less capable of producing change. The universe is not losing energy; it is losing the ability to use energy to create structure, motion, and life.

The Birth of Entropy in Thermodynamics

Entropy first emerged in the nineteenth century during the industrial revolution, a time when steam engines were transforming society. Engineers and scientists were obsessed with efficiency. They wanted to know why no engine, no matter how well designed, could ever convert all its heat into useful work. There always seemed to be some unavoidable waste.

This puzzle led to the formulation of the second law of thermodynamics, one of the most important laws in all of physics. In simple terms, the second law states that in an isolated system, entropy never decreases. It either increases or, in idealized limiting cases, remains constant. This law explains why heat flows spontaneously from hot objects to cold ones, but never in reverse unless external work is done.

Entropy, in this thermodynamic sense, is closely tied to irreversibility. Many processes in nature can happen easily in one direction but not the other. A shattered glass does not spontaneously reassemble. Smoke disperses into air but does not gather itself back into a cigarette. These processes are not forbidden by the conservation of energy, but they are forbidden by the second law of thermodynamics. Entropy provides the arrow that distinguishes past from future.

Entropy and the Direction of Time

One of the most emotionally powerful aspects of entropy is its connection to time. At the microscopic level, the fundamental laws of physics are largely time-symmetric. Equations describing the motion of particles work just as well if time runs forward as if it runs backward. Yet our everyday experience is profoundly time-directed. We remember the past, not the future. We see causes precede effects. We grow older, not younger.

Entropy explains this asymmetry. The direction in which entropy increases defines what physicists call the arrow of time. Processes that increase entropy are overwhelmingly more probable than those that decrease it. While it is not strictly impossible for entropy to decrease locally, such events are so astronomically unlikely that they never occur on macroscopic scales.

This connection between entropy and time gives the concept a deeply human resonance. Our lives are embedded in a universe where entropy increases, where memories accumulate, and where possibilities narrow as energy degrades. The flow of time, which feels so fundamental to our existence, is intimately tied to the statistical behavior of countless particles obeying the laws of thermodynamics.

Disorder, Order, and a Common Misunderstanding

Entropy is often described as a measure of disorder, but this description, while useful, can be misleading. Disorder is a subjective term, shaped by human intuition. Entropy, by contrast, has a precise quantitative definition rooted in physics.

A more accurate way to think about entropy is in terms of the number of microscopic configurations, or microstates, that correspond to a given macroscopic state. A system with high entropy can be realized in many different microscopic ways, while a system with low entropy has far fewer possible arrangements.

Consider a deck of cards. A perfectly ordered deck has very low entropy because there are few arrangements that match that specific order. A shuffled deck has high entropy because there are countless arrangements that all look equally random. When systems evolve naturally, they tend to move toward states with more possible microstates simply because those states are vastly more probable.

This statistical perspective reveals that entropy increase is not driven by a mysterious force toward chaos. It is driven by probability. The universe evolves from less probable states to more probable ones, and entropy is the mathematical measure of that progression.

Boltzmann and the Statistical Meaning of Entropy

The deep connection between entropy and probability was clarified by the Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann in the late nineteenth century. Boltzmann showed that entropy is related to the number of microscopic configurations available to a system through a simple and elegant formula engraved on his tombstone.

In Boltzmann’s view, the second law of thermodynamics is not an absolute law in the same sense as energy conservation. Instead, it is a statistical law. Entropy increases because systems naturally evolve toward states that can be realized in more ways at the microscopic level. While a decrease in entropy is not forbidden by the laws of mechanics, it is so unlikely for systems with many particles that it effectively never happens.

This statistical interpretation resolved long-standing debates and deepened the meaning of entropy. It also introduced a subtle tension between determinism and probability. The motion of individual particles may be governed by precise equations, but the collective behavior of enormous numbers of particles gives rise to probabilistic laws that define the direction of time itself.

Entropy in Open Systems and the Illusion of Local Order

If entropy always increases, how can order exist at all? How can stars form, crystals grow, and life evolve in a universe supposedly sliding toward disorder? This apparent contradiction is resolved by recognizing that entropy applies differently to open and closed systems.

The second law strictly applies to isolated systems, which exchange neither energy nor matter with their surroundings. Most systems of interest, including Earth and living organisms, are not isolated. They receive energy from their environment and export entropy back into it.

Life on Earth is a striking example. Living organisms maintain and even increase their internal order by consuming low-entropy energy, primarily from sunlight, and releasing higher-entropy energy in the form of heat. The total entropy of the universe still increases, even though local pockets of order temporarily arise.

This perspective transforms entropy from a symbol of inevitable decay into a dynamic principle that allows complexity to emerge under the right conditions. Order is not a violation of the second law but a consequence of it, enabled by energy flows that increase entropy elsewhere.

Entropy and the Engines of Civilization

Human civilization itself is built on entropy gradients. Every machine, from a steam engine to a smartphone, operates by exploiting differences in energy concentration. Heat engines convert temperature differences into work. Electrical devices rely on voltage differences. Even biological metabolism depends on chemical gradients.

No process can convert energy with perfect efficiency. Some energy is always dissipated as waste heat, increasing entropy. This inefficiency is not due to poor engineering alone but reflects a fundamental limit imposed by the second law of thermodynamics.

Understanding entropy is therefore essential for addressing modern challenges related to energy use and sustainability. Renewable energy sources, energy storage technologies, and efficiency improvements all operate within the constraints set by entropy. Physics does not dictate social choices, but it sets the boundaries within which those choices must be made.

Entropy on a Cosmic Scale

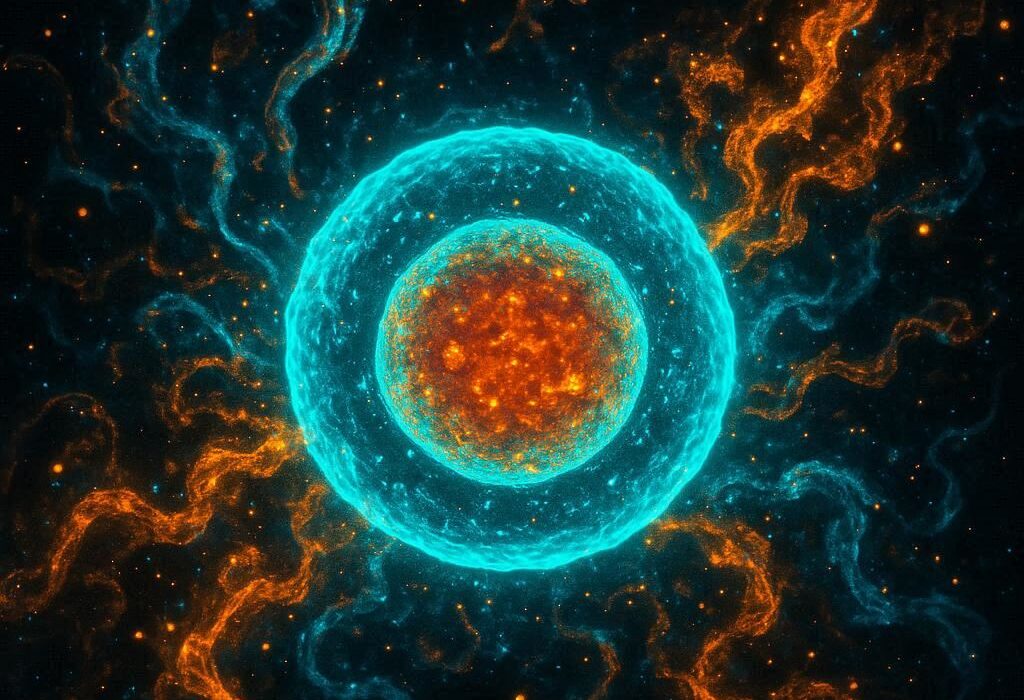

Entropy is not confined to laboratories or engines; it governs the evolution of the universe itself. Cosmology reveals that the universe began in an extraordinarily low-entropy state. Despite being extremely hot and dense, the early universe was remarkably uniform, with matter and energy distributed almost evenly.

This low-entropy beginning is one of the deepest mysteries in physics. It set the stage for the arrow of time and allowed structure to form as the universe expanded and cooled. Gravity played a crucial role, amplifying tiny density fluctuations into galaxies, stars, and planets.

As the universe evolves, entropy increases on ever-larger scales. Stars burn nuclear fuel, converting low-entropy nuclear energy into higher-entropy radiation. Black holes form, carrying enormous entropy associated with their event horizons. Over vast timescales, energy becomes increasingly spread out and less capable of doing work.

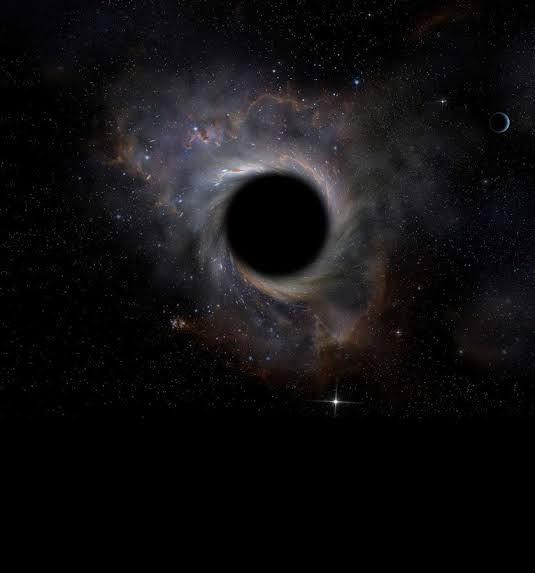

Black Holes and the Ultimate Entropy

Black holes represent one of the most surprising chapters in the story of entropy. Once thought to be simple gravitational sinks, black holes are now understood to possess entropy and temperature. The entropy of a black hole is proportional to the area of its event horizon, not its volume, a result that hints at deep connections between gravity, thermodynamics, and quantum theory.

Black holes are extraordinarily efficient at increasing entropy. When matter falls into a black hole, the entropy of the universe increases dramatically. Over time, black holes may come to dominate the entropy budget of the universe.

Yet black holes are not eternal. According to theoretical predictions, they slowly lose energy through a process known as Hawking radiation, eventually evaporating. This radiation further increases entropy, contributing to the gradual degradation of usable energy across the cosmos.

The Heat Death of the Universe

The ultimate implication of entropy on a cosmic scale is a scenario known as heat death. In this far-future vision, the universe reaches a state of maximum entropy. Energy is evenly distributed, temperature differences vanish, and no process capable of doing work remains possible.

Stars burn out, galaxies fade, and even black holes evaporate. What remains is a cold, dark, dilute universe in which nothing of interest happens. Time still exists in a mathematical sense, but without change, it loses its physical significance.

Heat death is not a dramatic explosion or collapse; it is a quiet fading away. This prospect can feel emotionally unsettling, as it suggests an end not only to life but to all meaningful activity. Yet it is important to recognize that this scenario unfolds over timescales so vast that they defy ordinary comprehension.

Entropy, Information, and Knowledge

In the twentieth century, entropy found new meaning in the context of information theory. Information entropy measures uncertainty or lack of information, drawing a formal analogy with thermodynamic entropy. This connection has profound implications for physics, computation, and communication.

When information is erased, entropy increases. This principle links the abstract act of computation to physical processes and energy dissipation. It also reinforces the idea that knowledge and order are not free; they require energy and produce entropy.

This relationship adds another layer of emotional depth to entropy. It suggests that even acts of knowing and remembering are embedded in the physical flow of energy and time. Memory itself is a low-entropy structure maintained at an energetic cost.

Why the Universe Had to Start with Low Entropy

One of the most profound unanswered questions in physics is why the universe began in such a low-entropy state. The second law explains why entropy increases, but it does not explain the initial condition that made this increase possible.

Various hypotheses have been proposed, ranging from cosmological inflation to deeper principles not yet understood. What is clear is that without a low-entropy beginning, there would be no arrow of time, no stars, no life, and no observers to ask these questions.

This realization transforms entropy from a bleak prediction into a condition for existence. The universe’s slow march toward equilibrium is also the reason why complexity and meaning can arise at all, at least temporarily.

Living with Entropy

Entropy is often portrayed as the enemy of life and order, but this view is incomplete. Life does not exist despite entropy; it exists because of it. The flow of energy from high to low concentration creates opportunities for complexity to emerge.

Every heartbeat, every thought, every creative act is powered by entropy gradients. While the long-term fate of the universe may be one of exhaustion, the present is rich with structure precisely because entropy has not yet reached its maximum.

Recognizing this can inspire a sense of urgency and appreciation. The universe is not static; it is a process. Moments of order, beauty, and meaning are precious because they are temporary configurations in a vast thermodynamic story.

Conclusion: Entropy as a Cosmic Narrative

Entropy tells a story that spans from the birth of the universe to its distant future. It explains why time flows forward, why energy degrades, and why complexity can exist only for a while. Far from being a dry technical concept, entropy is a narrative principle that shapes reality at every scale.

The universe is not running out of energy, but it is slowly losing the ability to use energy in ways that create change and structure. This insight is both humbling and illuminating. It reminds us that existence unfolds within physical limits, yet within those limits lies astonishing richness.

To understand entropy is to understand something essential about our place in the cosmos. We are temporary islands of order in an ever-expanding sea of equilibrium, made possible by a universe that began far from balance. In that fleeting imbalance lies all of history, all of life, and all of meaning we are capable of creating.