Long before Earth had oceans, continents, or even a solid surface, something violent and distant may have quietly shaped its destiny. A massive star reached the end of its life and exploded, sending a flood of energy and particles across space. According to new research published in the journal Science Advances, that event may not have been unusual or uniquely lucky. Instead, it may point to a common cosmic process that helps create rocky planets like our own.

The study suggests that when our solar system was forming, a nearby supernova bathed it in cosmic rays carrying radioactive ingredients crucial for building dry, rocky worlds. If this mechanism is widespread, then Earth-like planets may be far more common throughout the galaxy than scientists once believed.

The Mystery of Dry Worlds

Earth and other rocky planets are thought to form from planetesimals, early building blocks made of rock and ice. For these planetesimals to become dry enough to form solid, Earth-like worlds, they had to lose much of their water early in the solar system’s history. That drying process required intense heat.

The primary source of that heat came from the radioactive decay of short-lived radionuclides, known as SLRs. One of the most important of these was aluminum-26. As it decayed, it released energy that warmed young planetesimals from the inside, driving off water and reshaping their internal structures.

Meteorites, which serve as time capsules from the early solar system, preserve clear evidence of these radioactive materials. Their composition confirms that SLRs were abundant when the solar system was young. Yet for years, scientists have struggled to explain exactly how so much radioactive material arrived at just the right time.

When Old Models Fell Apart

For a long time, supernovae were considered the most likely source of these short-lived radionuclides. The logic was simple. When a massive star explodes, it creates and releases radioactive elements into surrounding space. If a forming solar system happened to be nearby, it could capture some of that material.

But there was a serious problem. Models that relied on a supernova as the sole source of SLRs could not accurately reproduce the quantities found in meteorites. To deliver enough radioactive material directly, the exploding star would have needed to be dangerously close.

So close, in fact, that the explosion would have destroyed the very thing it was supposed to enrich. The delicate disk of dust and gas where planets were forming would not have survived such a blast. The numbers simply did not add up, leaving scientists with a puzzle that refused to go away.

A New Idea Emerges From the Shockwave

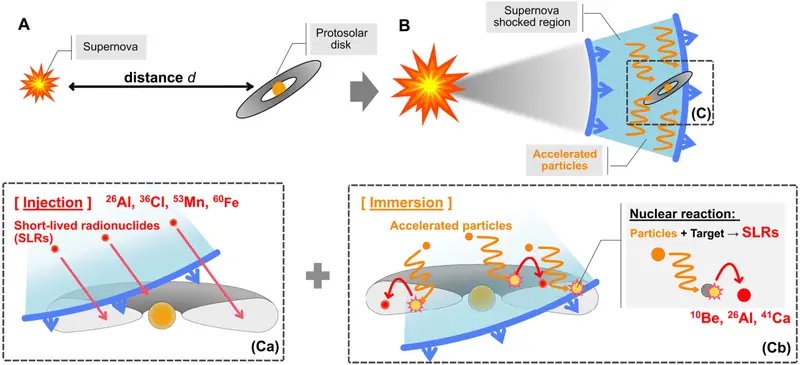

To solve this mystery, Ryo Sawada of the University of Tokyo and his colleagues proposed a new concept they call the immersion mechanism. Instead of placing the supernova right on top of the young solar system, their model positions it about 3.2 light-years away. This distance is close enough to influence the system, but far enough to leave the planet-forming disk intact.

When the supernova exploded, it generated a powerful shockwave that raced through surrounding space. This shockwave accelerated particles, mainly protons, to extreme energies. These particles became trapped as cosmic rays, filling the nearby environment with radiation.

Rather than relying on a single delivery method, the immersion mechanism introduces a two-part story of how radioactive materials reached the young solar system.

Two Paths, One Outcome

According to the model, some short-lived radionuclides were delivered directly. Elements such as iron-60 were carried into the planet-forming disk as dust grains produced by the supernova itself. These grains drifted into the disk and became part of the raw material from which planets would eventually form.

At the same time, the cosmic rays generated by the explosion played a second, equally important role. As they bombarded the disk, they slammed into stable materials at enormous energies. These collisions triggered nuclear reactions that created new short-lived radionuclides inside the disk itself. Aluminum-26, the key heat source for drying planetesimals, could be produced this way.

In this scenario, the solar system was not just a passive recipient of radioactive debris. It was immersed in a storm of cosmic energy that actively generated the ingredients needed to shape rocky worlds.

When the Numbers Finally Match

When the research team ran their model, the results were striking. The combination of direct injection and cosmic-ray-driven reactions produced quantities of radioactive materials that closely matched those found in meteorites. For the first time, a supernova-based explanation fit the evidence without destroying the planet-forming disk.

This success transformed the immersion mechanism from an interesting idea into a powerful solution. It showed how a nearby stellar explosion could gently influence a young solar system, delivering exactly what was needed at exactly the right time.

Looking Outward Into the Galaxy

The implications of this finding extend far beyond our own solar system. If the immersion mechanism can operate elsewhere, then the conditions that produced Earth may not be rare at all.

The researchers point directly to this possibility in their paper, writing, “Our results suggest that Earth-like, water-poor rocky planets may be more prevalent in the galaxy than previously thought, given that 26Al abundance plays a key role in regulating planetary water budgets.”

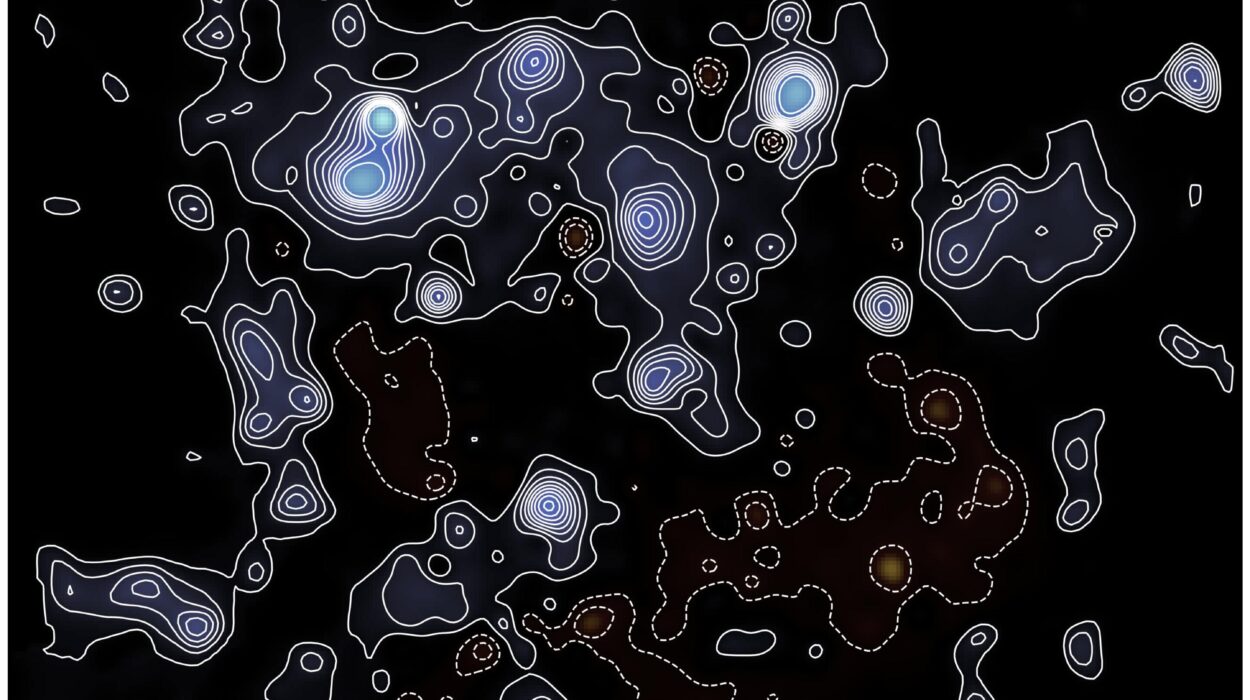

Their models suggest that around 10% to 50% of sun-like stars may have hosted planet-forming disks with short-lived radionuclide abundances similar to those of our solar system. That range implies that many young stars could have been bathed in cosmic rays from nearby supernovae, quietly setting the stage for rocky planet formation.

Why This Research Matters

This study reshapes how scientists think about the birth of Earth-like worlds. Instead of requiring a rare and perfectly timed event, rocky planet formation may be a natural outcome of star-forming environments where massive stars live and die near their smaller neighbors.

By showing how a supernova can safely and efficiently deliver the radioactive heat sources needed to dry planetesimals, the immersion mechanism offers a new lens through which to view planetary origins. It suggests that the same cosmic violence that ends a star’s life may help spark the conditions for new worlds to emerge.

Most importantly, this research expands the possibilities for finding other rocky, potentially habitable planets in the galaxy. If Earth’s formation story is not unique, then the universe may be filled with worlds shaped by similar stellar echoes, waiting to be discovered.

More information: Ryo Sawada et al, Cosmic-ray bath in a past supernova gives birth to Earth-like planets, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx7892