For years, the soft hum of tanning beds promised a quick glow, a controlled slice of summer no matter the season. They offered warmth, color, confidence. But beneath that familiar light, something far more troubling was happening. A new study led by Northwestern Medicine and the University of California, San Francisco has revealed, for the first time, how tanning beds damage DNA in a way that reaches nearly the entire surface of the skin, sharply increasing the risk of melanoma.

The findings, published in Science Advances, show that tanning bed use is tied to almost a three-fold increase in melanoma risk. More than that, they uncover the biological footprint left behind by indoor tanning, mutations that quietly spread across the skin, even in places that rarely, if ever, see sunlight.

This research does more than add another warning. It tells a story written directly into human cells.

A Cancer With a Heavy Toll

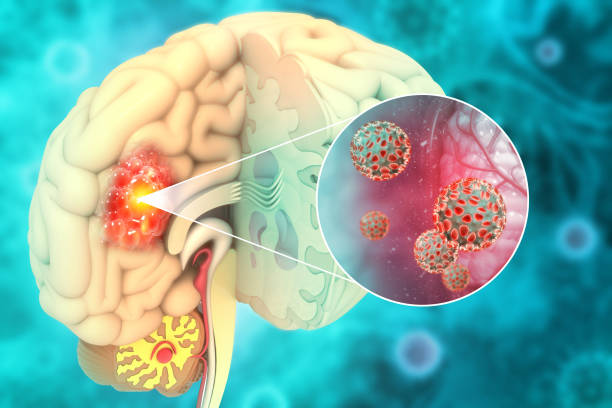

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer, killing about 11,000 people in the United States each year. For decades, public health messages have warned about the dangers of indoor tanning, yet one crucial piece was missing. Scientists knew the risk was higher, but they had not fully shown how tanning beds caused the kind of DNA damage that leads to melanoma.

That uncertainty created space for doubt. The indoor tanning industry, now experiencing a comeback, has leaned on the lack of a clear biological explanation to argue that tanning beds are no more harmful than sunlight.

This new study directly confronts that claim. According to the authors, it shows “irrefutably” that tanning beds mutate skin cells at a molecular level in a way that goes far beyond ordinary sun exposure.

A Doctor’s Uneasy Pattern

The study began not in a lab, but in a clinic.

For 20 years, Dr. Pedram Gerami has treated melanoma patients. As director of the melanoma program in dermatology at Northwestern, he has seen countless cases. But over time, one pattern began to trouble him. An unusually high number of women under 50 were arriving with histories of multiple melanomas.

They were young. They were otherwise healthy. And again and again, one detail appeared in their histories. Tanning bed use.

That observation became a question, and the question became a study.

Following the Numbers

Gerami and his research team designed the epidemiologic part of the study to test whether his clinical impressions held up under scrutiny. They compared medical records from roughly 3,000 people who had used tanning beds with 3,000 age-matched individuals who had never tanned indoors.

The difference was striking. Melanoma was diagnosed in 5.1% of tanning bed users, compared with 2.1% of non-users. Even after adjusting for age, sex, sunburn history, and family history, tanning bed use remained associated with a 2.85-fold increase in melanoma risk.

The location of the cancers raised even more concern. Tanning bed users were more likely to develop melanoma on sun-shielded parts of the body, such as the lower back and buttocks. These are areas that typically escape intense outdoor sun exposure.

The findings hinted at something different, something broader than what sunlight alone usually causes.

Searching for Damage Beneath the Skin

To understand what was happening at a deeper level, the researchers turned to DNA sequencing. They wanted to see whether tanning beds were leaving a genetic signature behind.

Using new genomic technologies, the scientists performed single-cell DNA sequencing on melanocytes, the pigment-producing skin cells where melanoma begins. They examined cells from three distinct donor groups.

The first group included 11 patients with long histories of indoor tanning. The second group consisted of nine patients who had never used tanning beds but were matched for age, sex, and cancer risk profiles. A third group of six cadaver donors provided additional skin tissue to strengthen the control samples.

In total, the scientists sequenced 182 individual melanocytes, reading each cell’s genetic history letter by letter.

What they found was impossible to ignore.

Mutations Everywhere the Light Reached

Melanocytes from tanning bed users carried nearly twice as many mutations as those from people who had never tanned indoors. Even more alarming, these cells were far more likely to contain mutations linked specifically to melanoma.

The damage was not limited to areas typically exposed to the sun. In people who used tanning beds, melanoma-linked mutations appeared in body regions that normally remain protected.

“Even in normal skin from indoor tanning patients, areas where there are no moles, we found DNA changes that are precursor mutations that predispose to melanoma,” said study first author Dr. Pedram Gerami, professor of skin cancer research at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “That has never been shown before.”

He explained the difference in scope between natural sun exposure and tanning beds in simple terms. “In outdoor sun exposure, maybe 20% of your skin gets the most damage,” Gerami said. “In tanning bed users, we saw those same dangerous mutations across almost the entire skin surface.”

The light inside tanning beds, it turns out, does not behave like a limited summer sun. It blankets the body, leaving behind a wide field of DNA injury.

The Human Cost Written in Scars

Behind every sequenced cell was a person. The study depended on patients willing to donate skin biopsies, sometimes repeatedly, so scientists could understand what was happening beneath the surface.

One of those patients was Heidi Tarr, a 49-year-old from the Chicago area. As a teenager, she used tanning beds heavily, two to three times a week during high school. At the time, it felt normal, even desirable. Friends were doing it. Celebrities were doing it. “It felt like that’s what made you beautiful.”

Years later, life looked very different.

As a mother in her thirties, Tarr noticed a mole on her back. Fear arrived instantly. Her diagnosis of melanoma led to surgery, years of frequent follow-up visits, and more than 15 additional biopsies as new moles appeared.

“The biopsies can be painful, but the mental anxiety is worse,” she said. “You’re always waiting for the call that it’s melanoma again.”

When Gerami explained the study and what it aimed to uncover, Tarr did not hesitate. She volunteered additional biopsies, despite everything she had already endured.

“I value science, and I wanted to help,” she said. “If what happened to my skin can help others understand the real risks of tanning beds, then it matters.”

Evidence That Changes the Conversation

For Gerami, seeing the clinical data and the molecular evidence side by side was a turning point. The patterns he had observed for years now had a clear biological explanation.

The mutations were real. They were widespread. And they were directly linked to indoor tanning.

After reviewing the findings, Gerami said the implications extend beyond medicine and into policy. “At the very least, indoor tanning should be illegal for minors,” he said.

He reflected on the stories his patients tell him. “Most of my patients started tanning when they were young, vulnerable and didn’t have the same level of knowledge and education they have as adults,” he said. “They feel wronged by the industry and regret the mistakes of their youth.”

He believes tanning beds should carry warnings similar to those found on cigarette packages. “When you buy a pack of cigarettes, it says this may result in lung cancer,” he said.

“We should have a similar campaign with tanning bed usage. The World Health Organization has deemed tanning beds to be the same level of carcinogen as smoking and asbestos. It’s a class one carcinogen.”

Why This Discovery Matters

This study does more than confirm that tanning beds are dangerous. It shows how they harm the body, cell by cell, mutation by mutation, across nearly the entire skin surface. It closes a long-standing gap between epidemiology and biology, replacing uncertainty with clear molecular evidence.

For individuals, the findings offer a reason to take past tanning seriously. Gerami suggests that anyone who frequently tanned earlier in life should have a total-body skin exam by a dermatologist and be evaluated for whether routine skin checks are needed.

For society, the research challenges lingering claims that indoor tanning is no worse than sunlight. It reveals that the damage is broader, deeper, and written permanently into the DNA of skin cells.

And for future patients, especially young people still deciding whether to step into a tanning bed, this study offers something powerful. It offers knowledge grounded in evidence, shaped by human stories, and illuminated by science.

The glow, it turns out, comes at a cost that lasts far longer than a season.

More information: Pedram Gerami et al, Molecular effects of indoor tanning, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ady4878. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ady4878