Imagine eating something as ordinary as a slice of bread or a comforting bowl of pasta—and instead of nourishment, your body launches an attack against itself. For millions of people worldwide, this is not imagination but reality. This condition is known as celiac disease, an autoimmune disorder that silently damages the small intestine when gluten, a common protein found in wheat, barley, and rye, is consumed.

Celiac disease is far more than a food intolerance. It is not a dietary preference, nor is it a passing sensitivity. It is a lifelong condition with potentially serious consequences if left untreated. For those affected, even a tiny crumb of gluten can trigger inflammation, damage intestinal tissue, and cause a cascade of symptoms ranging from digestive distress to neurological complications. Yet, despite its seriousness, celiac disease is often misunderstood, misdiagnosed, or overlooked entirely.

To understand celiac disease is to delve into the intricate interplay between genetics, immunity, and nutrition—and to recognize the immense resilience of people who live with it.

What Exactly Is Celiac Disease?

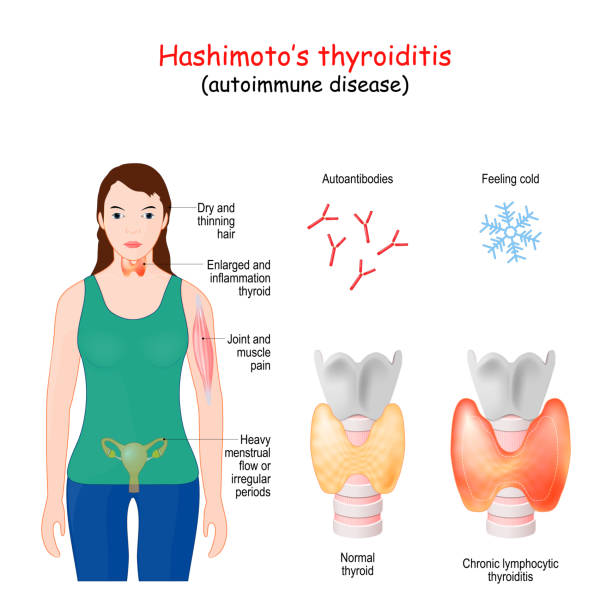

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system mistakenly reacts to gluten, a protein found in grains like wheat, rye, and barley. When someone with celiac disease eats gluten, their immune system mounts an attack not only against the protein but also against the body’s own tissues, particularly the lining of the small intestine.

The small intestine is covered in finger-like projections called villi, which absorb nutrients from food. In celiac disease, the immune reaction damages or destroys these villi, flattening them and drastically reducing the intestine’s ability to absorb essential vitamins, minerals, and calories. Over time, this malabsorption can lead to malnutrition, anemia, bone loss, infertility, neurological issues, and even increased risk of certain cancers.

Unlike a wheat allergy, which is triggered by the immune system’s production of antibodies against wheat proteins, or non-celiac gluten sensitivity, which involves uncomfortable symptoms without autoimmune damage, celiac disease is a systemic, lifelong condition that requires strict medical attention and dietary management.

The Causes: A Complex Interplay of Genes and Environment

Celiac disease does not arise from a single cause; it is the product of multiple interacting factors.

Genetic Predisposition

The strongest known contributors to celiac disease are genetics. Approximately 95% of individuals with celiac disease carry a specific genetic marker known as HLA-DQ2, while most of the rest carry HLA-DQ8. These genes are involved in presenting gluten-derived peptides to immune cells, triggering the autoimmune cascade. However, not everyone with these genes develops the condition. In fact, many people carry HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 and remain completely healthy. This shows that genes alone are not enough—they set the stage, but other factors must tip the balance.

Environmental Triggers

Environmental factors play a critical role in whether celiac disease emerges. Gluten exposure is, of course, the central trigger, but timing and quantity may influence disease onset. Research suggests that early-life infections, microbiome imbalances, and possibly even mode of birth (cesarean versus vaginal delivery) can contribute to risk. Stressful life events, major surgery, pregnancy, or other autoimmune diseases can also act as triggers for the disease to manifest later in life.

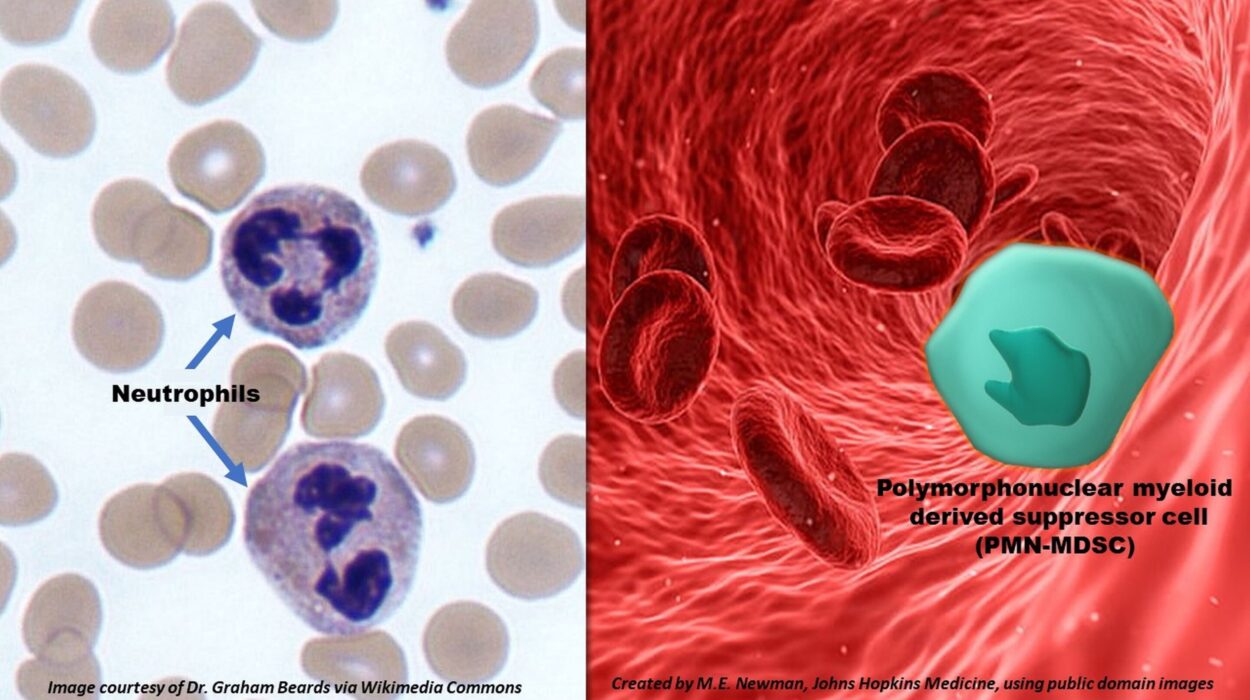

The Immune System’s Overreaction

In celiac disease, the immune system mistakes gluten peptides as dangerous invaders. Specialized immune cells present these peptides to T-cells, which release inflammatory chemicals. One of the enzymes involved, tissue transglutaminase (tTG), modifies gluten proteins in a way that makes them even more likely to trigger immune responses. The immune system then generates antibodies against both gluten and tTG—leading to the autoimmune damage that defines the condition.

Symptoms: The Many Faces of Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is often called a “great imitator” because its symptoms vary widely from person to person and can mimic many other conditions. Some people suffer from classic digestive symptoms, while others experience issues that seem unrelated to the gut. This variability makes diagnosis challenging and contributes to the condition being underdiagnosed worldwide.

Digestive Symptoms

In children and adults alike, digestive problems may be the first clues. These include bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and unexplained weight loss. For some, eating gluten results in immediate and severe discomfort; for others, symptoms are subtle and accumulate gradually over time.

Non-Digestive Symptoms

One of the most striking aspects of celiac disease is that many of its most serious symptoms occur outside the digestive tract. Fatigue, anemia, osteoporosis, infertility, migraines, neurological issues such as peripheral neuropathy, and skin disorders like dermatitis herpetiformis are all linked to untreated celiac disease. Some individuals experience brain fog, irritability, or even depression.

Children may show slowed growth, delayed puberty, irritability, or dental enamel defects. Adults may face complications such as early-onset osteoporosis or liver dysfunction.

Silent Celiac Disease

Some people with celiac disease have no noticeable symptoms at all, despite significant intestinal damage. This is sometimes discovered only during screening for another autoimmune condition or family history. Silent cases are particularly dangerous because untreated damage can still lead to long-term complications.

Diagnosis: Unraveling the Mystery

Because celiac disease presents with such varied symptoms, diagnosis requires a careful, stepwise approach combining medical history, blood tests, and intestinal biopsies.

Serological Testing

The first step in diagnosis usually involves blood tests to detect specific antibodies. The most commonly used tests measure anti-tTG (tissue transglutaminase) IgA antibodies. Elevated levels suggest the immune system is reacting abnormally to gluten. Other tests, such as deamidated gliadin peptide (DGP) antibodies or endomysial antibodies (EMA), may also be used, especially in children.

It is crucial that individuals remain on a gluten-containing diet during testing; removing gluten beforehand can cause antibody levels to drop and yield false negatives.

Genetic Testing

Genetic tests can determine whether a person carries the HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 genes. While not diagnostic on their own, a negative result makes celiac disease highly unlikely, since these genes are present in almost all cases.

Endoscopy and Biopsy

If blood tests suggest celiac disease, the gold standard for confirmation is an endoscopy with small intestinal biopsy. A flexible camera allows physicians to view the lining of the small intestine and collect tissue samples. Under the microscope, hallmark features such as villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and increased intraepithelial lymphocytes can be observed.

Challenges in Diagnosis

Because symptoms can be subtle or mimic other conditions like irritable bowel syndrome, lactose intolerance, or anemia, diagnosis is often delayed by years. In fact, many people live with celiac disease for a decade or more before receiving a definitive answer. This delay increases the risk of long-term complications.

Treatment: A Lifelong Commitment to Gluten-Free Living

At present, there is no cure for celiac disease—no pill or surgery can restore tolerance to gluten. The only proven treatment is a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet.

Eliminating Gluten

For someone with celiac disease, avoiding gluten is not optional—it is essential. Even trace amounts can trigger immune reactions and intestinal damage. This means avoiding not only obvious sources like bread, pasta, and beer, but also hidden gluten in sauces, soups, candies, processed foods, and even medications or cosmetics.

Adapting to this diet requires vigilance, label-reading skills, and often a steep learning curve. Eating out becomes a careful negotiation, as cross-contamination in kitchens can render a meal unsafe. Social events, travel, and cultural traditions around food all require adaptation and resilience.

Recovery and Healing

Once gluten is removed, the intestine begins to heal. Children often recover within months, while adults may take years to fully restore intestinal health. Symptoms gradually subside, energy levels improve, and long-term risks decrease significantly. However, healing requires unwavering commitment; even occasional gluten exposure can set back progress.

Nutritional Support

Because celiac disease often causes deficiencies before diagnosis, nutritional support is critical. Iron, calcium, vitamin D, vitamin B12, folate, and zinc are commonly low. A dietitian specializing in celiac disease can help individuals build a balanced, gluten-free diet that restores nutrient levels.

Ongoing Monitoring

Even after diagnosis, regular medical follow-up is essential. Doctors may order blood tests to monitor antibody levels and ensure dietary compliance. In some cases, repeat endoscopy may be necessary to check healing.

Beyond the Diet: Research on Future Therapies

Researchers are exploring potential treatments that could complement or reduce dependence on a gluten-free diet. These include enzyme supplements to break down gluten, drugs that block immune activation, vaccines that induce tolerance, and therapies to strengthen the intestinal barrier. While none are ready for widespread use, they offer hope for less restrictive options in the future.

The Emotional and Social Impact of Celiac Disease

Living with celiac disease is not only a medical journey but also an emotional and social one. Food is deeply woven into human culture, family traditions, and celebrations. Having to scrutinize every meal can feel isolating. Children may feel left out at birthday parties; adults may feel burdensome when dining with friends.

The psychological impact should not be underestimated. Anxiety about accidental gluten exposure, frustration over dietary restrictions, and the ongoing vigilance required can lead to stress and, in some cases, depression. Support from family, healthcare professionals, and patient advocacy groups plays a vital role in emotional well-being.

Yet, many people with celiac disease also report positive transformations. They discover new foods, develop resilience, and build communities with others facing similar challenges. For many, the diagnosis becomes a turning point—a shift toward healthier living and self-awareness.

Complications of Untreated Celiac Disease

When undiagnosed or untreated, celiac disease can cause serious complications. Persistent malabsorption may lead to osteoporosis, anemia, infertility, miscarriages, neurological problems, and delayed growth in children. Long-term inflammation increases the risk of small intestinal lymphoma and other gastrointestinal cancers.

This highlights the importance of early diagnosis and strict adherence to the gluten-free diet—not only to alleviate symptoms but to prevent life-threatening complications.

The Global Perspective: Prevalence and Awareness

Celiac disease affects approximately 1% of the world’s population, but prevalence varies across regions. It is most common in populations of European descent but increasingly recognized in Asia, Africa, and South America. With globalization of food systems and better diagnostic tools, awareness is rising worldwide.

Still, underdiagnosis remains a major challenge. For every person diagnosed, many more may remain undetected, suffering silently. Public awareness campaigns, medical education, and broader screening programs are essential to bridging this gap.

Living Well With Celiac Disease

Despite its challenges, people with celiac disease can lead full, vibrant lives. With education, support, and careful dietary management, health can be restored, energy regained, and complications prevented. Advances in food technology have led to a growing variety of gluten-free products, making it easier than ever to maintain the diet without sacrificing enjoyment.

The key lies in empowerment—learning how to manage the condition, advocate for one’s needs, and build a support network. From schools adapting lunch programs to restaurants offering gluten-free menus, society’s increasing accommodation is reshaping what it means to live with celiac disease.

Conclusion: A Journey of Awareness, Adaptation, and Strength

Celiac disease is more than a medical diagnosis; it is a journey that reshapes how individuals interact with one of life’s most fundamental elements—food. It is a condition rooted in genetics and immunity, but its impact extends into culture, identity, and daily living.

Though incurable, it is manageable, and with proper diagnosis, treatment, and support, people with celiac disease can thrive. The road requires discipline, patience, and resilience, but it also opens doors to new communities, healthier habits, and deeper self-awareness.

Celiac disease challenges us to rethink health, food, and connection. It reminds us that what nourishes one body may harm another, and that awareness is the first step toward healing. For those living with celiac disease, each gluten-free meal is not just sustenance—it is an act of protection, of resilience, and of hope.