Imagine a man standing before a police officer, unable to even recall his own name, suspected of committing an offense he can barely describe. Picture a woman in her mid-fifties, repeatedly violating traffic laws, stubbornly convinced that nothing is wrong with her behavior. Should these individuals be treated as criminals in court? Or are they, in fact, patients—victims of a brain that is slowly betraying them?

These unsettling questions are not rare hypotheticals but growing realities in everyday clinical practice. Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and Parkinson’s disease do not only steal memory and motor skills—they can also profoundly alter personality, behavior, and judgment. One of the most surprising and often distressing consequences is the sudden appearance of criminal or socially inappropriate actions in people who may have lived law-abiding lives until their illness began.

Dementia and the Brain’s Fragile Balance

Dementia is not a single disease but an umbrella term for a variety of conditions that cause progressive decline in brain function. Depending on which brain regions are most affected, patients may lose memory, speech, motor control, or the ability to regulate emotions and impulses.

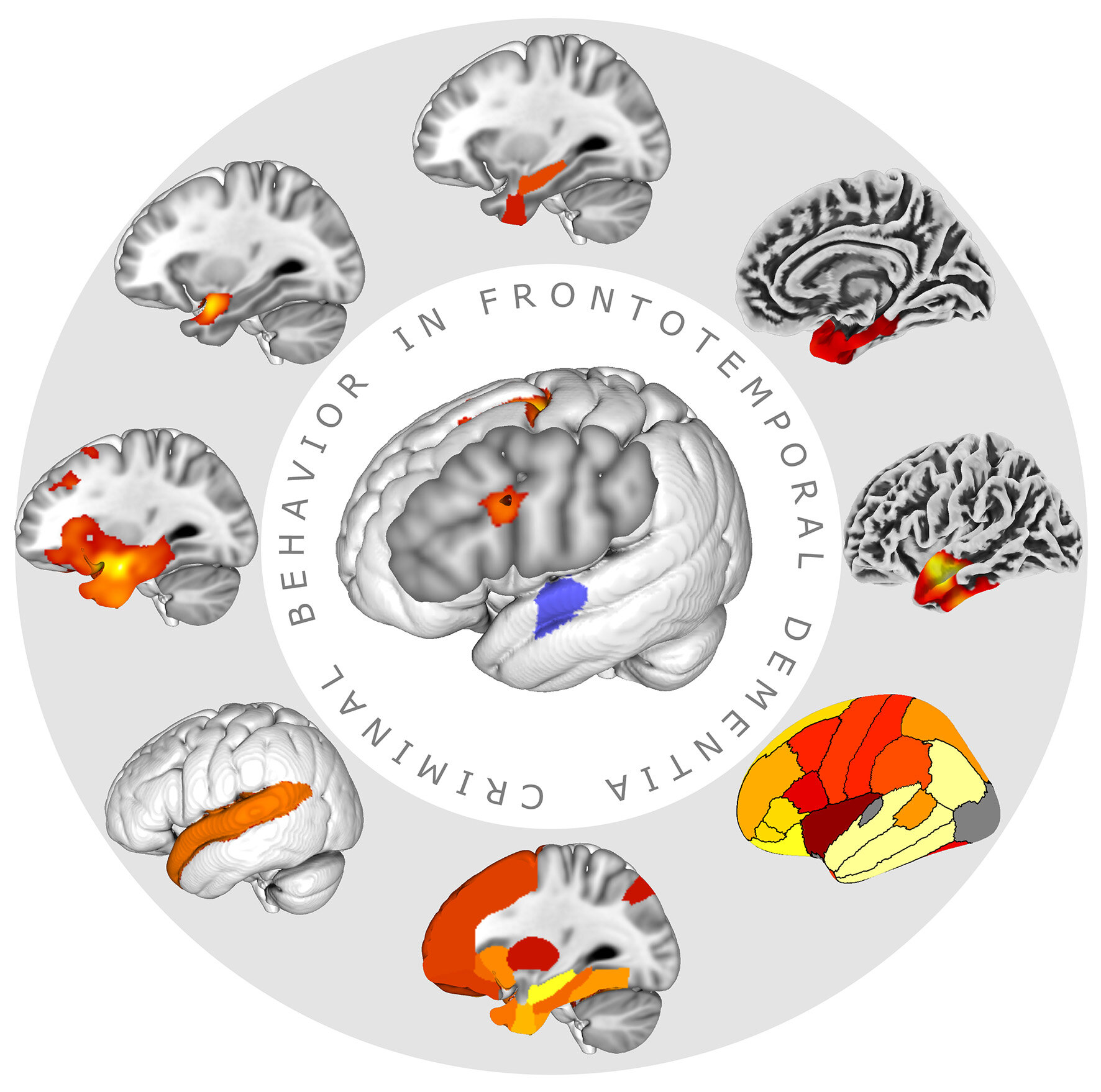

For example, Alzheimer’s disease primarily targets memory and cognition, while frontotemporal dementia disrupts the brain’s “control center” for personality, behavior, and decision-making. Parkinson’s disease, though usually thought of as a movement disorder, can also impact mood and executive function. When the brain’s delicate networks begin to deteriorate, the ability to distinguish right from wrong, to restrain impulses, or to act with empathy may fade away.

The result is behavior that might shock families, disrupt communities, and, in some cases, break the law.

When Illness Looks Like Crime

A systematic meta-analysis led by Matthias Schroeter and Lena Szabo at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences sought to quantify this troubling phenomenon. The team reviewed 14 studies across multiple countries, examining data from over 236,000 individuals. Their findings, published in Translational Psychiatry, revealed a clear but complex pattern:

- Criminal risk behaviors—such as harassment, traffic violations, theft, or aggression—were significantly more common in the early stages of certain dementias than in the general population.

- Strikingly, these behaviors often represented the very first signs of disease, appearing before a diagnosis had even been made.

- Over time, as dementia progressed and patients became more impaired, the frequency of criminal acts actually declined, eventually falling below population averages.

This paradox highlights a crucial point: criminal or socially disruptive behavior in otherwise law-abiding middle-aged adults could sometimes be a red flag for an undiagnosed neurodegenerative disease.

Different Dementias, Different Risks

Not all dementias carry the same risk of triggering unlawful behavior. Schroeter’s analysis revealed stark differences across syndromes:

- Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) showed the highest prevalence, with more than half of patients developing some form of criminal behavior.

- Semantic variant primary progressive aphasia followed at 40%.

- Vascular dementia and Huntington’s disease showed moderate levels (around 15%).

- Alzheimer’s disease presented a lower risk (around 10%).

- Parkinsonian syndromes were lowest, at less than 10%.

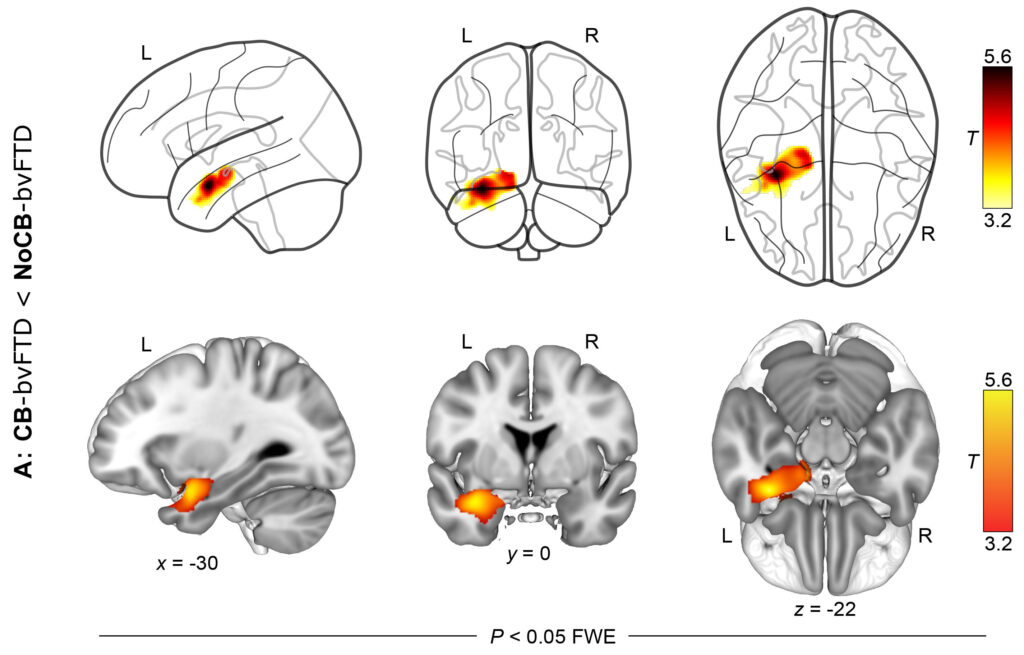

Why is frontotemporal dementia so strongly associated with such behaviors? The answer lies in the location of the damage. The frontal and temporal lobes—regions responsible for self-control, empathy, and social awareness—atrophy dramatically in bvFTD. As these structures shrink, so too does the patient’s ability to restrain impulses, regulate emotions, or consider consequences.

The result is disinhibition: a devastating neurological state in which actions are no longer filtered through judgment or restraint. A person who once respected boundaries may suddenly act with aggression, engage in theft, or commit indecent acts, not out of malice, but because the brain’s “brakes” have failed.

The Gender Divide

Another striking finding was the gender imbalance in dementia-related criminal behavior. Men were significantly more likely than women to exhibit such behaviors once dementia began. In fact, after diagnosis, men were found to commit four times as many criminal acts as women in frontotemporal dementia, and seven times more in Alzheimer’s disease.

The reasons for this difference remain unclear, though socialization, biology, and baseline risk factors likely play a role. Regardless, it underscores the importance of tailoring interventions and monitoring strategies according to patient risk profiles.

Between Compassion and Justice

These discoveries raise urgent ethical and legal questions. Should a person who assaults another during a state of dementia be punished in the same way as a healthy adult? If a previously law-abiding grandmother begins shoplifting because of frontal lobe degeneration, is she truly a criminal—or a patient?

Most of the offenses described in the research were minor: traffic violations, theft, or indecent behavior. Yet some cases did involve aggression or physical violence, which can have serious consequences for victims and families. The challenge for society is to protect both vulnerable patients and those they might harm, while avoiding unjust punishment of people whose actions are driven by disease, not intent.

Legal systems across the world are beginning to grapple with this reality. Awareness is growing that some offenses may reflect neurological illness rather than criminal intent. Courts and correctional facilities may need to adapt, integrating medical evaluation, psychiatric expertise, and compassionate sentencing options.

The Danger of Stigma

At the same time, experts like Schroeter warn against overreacting. Not every patient with dementia poses a criminal risk, and most never will. Overstating the link between dementia and crime risks adding to the stigma already faced by patients and their families.

Dementia is a condition that strips away independence, dignity, and cherished memories. To also burden patients with unfair suspicion of violence or lawbreaking would be a grave injustice. The challenge, then, is to raise awareness without fueling prejudice.

The Call for Early Diagnosis

One of the most powerful takeaways from these studies is the importance of early recognition. When a middle-aged or older adult begins to show uncharacteristic aggression, impulsive behavior, or unlawful acts, families and professionals should consider the possibility of dementia.

An early diagnosis not only helps protect the individual and others from harm but also opens the door to therapy, support, and planning for the future. Timely intervention may slow disease progression, reduce risk behaviors, and ease the burden on caregivers and communities.

Toward a More Compassionate Future

The intersection of dementia and crime is one of the most complex and emotionally charged challenges in modern healthcare and law. It forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about free will, responsibility, and the fragile nature of the human brain.

But it also calls us to compassion. To recognize that behind every troubling incident is a person whose identity, memories, and self-control are being eroded by disease. To remember that families, too, are struggling—often bewildered and heartbroken by behaviors they barely recognize in their loved ones.

Science, law, and society must come together to navigate this delicate terrain. With early diagnosis, better public awareness, and sensitive legal reforms, we can protect both patients and communities—without losing sight of our shared humanity.

More information: Matthias L. Schroeter et al, Criminal minds in dementia: A systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis, Translational Psychiatry (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41398-025-03523-z

Karsten Mueller et al, Criminal Behavior in Frontotemporal Dementia: A Multimodal MRI Study, Human Brain Mapping (2025). DOI: 10.1002/hbm.70308