Aging is the one biological experience shared by every human being. It begins silently, long before wrinkles appear or joints ache, unfolding at the level of cells, molecules, and genes. For most of history, aging was accepted as inevitable, a one-way journey toward decline and death. Yet in recent decades, science has begun to challenge this assumption. Researchers now ask a question that once belonged only to myth and fantasy: can aging itself be slowed, stopped, or even reversed?

This question sits at the intersection of biology, medicine, philosophy, and ethics. It provokes hope, skepticism, excitement, and fear in equal measure. On one hand, longevity research promises longer, healthier lives free from the chronic diseases that dominate old age. On the other, it raises concerns about overpopulation, inequality, and the meaning of mortality. To understand whether science can truly reverse aging, it is essential to first understand what aging is, why it happens, and what modern research has actually achieved so far.

What Aging Really Is: Beyond Wrinkles and Gray Hair

Aging is often mistaken for its visible signs, such as sagging skin, thinning hair, or reduced physical stamina. In reality, these outward changes are merely surface indicators of deeper biological processes. Aging is fundamentally the gradual accumulation of damage within cells and tissues, leading to a decline in physiological function and an increased vulnerability to disease.

At the cellular level, aging involves a complex interplay of genetic, metabolic, and environmental factors. Cells accumulate DNA damage over time, proteins lose their proper structure, and cellular waste products build up. Mitochondria, the energy-producing structures within cells, become less efficient. Stem cells lose their ability to regenerate tissues effectively. The immune system weakens, allowing infections and cancer to take hold more easily.

Importantly, aging is not caused by a single mechanism. It is a multifactorial process, meaning that many different biological pathways contribute to the gradual decline. This complexity is one of the greatest challenges facing longevity research. Unlike infectious diseases, which may have a single identifiable cause, aging emerges from the cumulative effects of countless small failures across the body’s systems.

The Evolutionary Roots of Aging

To understand why aging exists at all, scientists turn to evolutionary biology. From an evolutionary perspective, the primary goal of life is not longevity, but reproduction. Natural selection favors traits that increase the likelihood of passing genes to the next generation, even if those traits have harmful effects later in life.

Many theories of aging are rooted in this principle. One influential idea suggests that organisms invest their biological resources in growth and reproduction early in life, rather than in long-term maintenance and repair. As a result, damage accumulates over time. Another theory proposes that certain genes have beneficial effects in youth but detrimental effects in old age. These genes persist because their early advantages outweigh their later costs.

Evolution, therefore, has not optimized humans for extreme longevity. Instead, it has produced a balance between survival, reproduction, and energy efficiency. Aging, from this viewpoint, is not a programmed death sentence but a byproduct of evolutionary trade-offs. This insight has profound implications for longevity research, because it suggests that aging may be modifiable if its underlying mechanisms can be targeted.

The Shift from Treating Disease to Targeting Aging

Traditional medicine has approached aging indirectly, focusing on treating age-related diseases such as cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders. While this approach has significantly increased average life expectancy, it has not eliminated the period of frailty and illness that often accompanies old age.

Longevity research represents a conceptual shift. Instead of treating diseases one by one, scientists aim to address the root causes that make aging bodies susceptible to disease in the first place. This approach is sometimes described as extending healthspan rather than merely lifespan. Healthspan refers to the number of years a person lives in good health, free from serious illness or disability.

By targeting the biological mechanisms that drive aging, researchers hope to delay or prevent multiple diseases simultaneously. If aging itself can be slowed, the onset of many age-related conditions could be postponed together. This idea has transformed aging from an accepted fate into a legitimate scientific target.

Cellular Senescence and the Burden of Old Cells

One of the most intensively studied mechanisms of aging is cellular senescence. Senescent cells are cells that have permanently stopped dividing but refuse to die. Initially, this process serves a protective role, preventing damaged cells from becoming cancerous. Over time, however, senescent cells accumulate in tissues and begin to cause harm.

These cells secrete a mixture of inflammatory molecules, enzymes, and signaling factors that disrupt the surrounding tissue environment. This chronic, low-level inflammation contributes to tissue degeneration, impaired healing, and the progression of age-related diseases. In essence, senescent cells act as biological saboteurs, undermining the function of otherwise healthy tissues.

Animal studies have shown that selectively removing senescent cells can improve health and extend lifespan. Mice treated with compounds known as senolytics, which target senescent cells for destruction, exhibit improved physical function and delayed onset of age-related disorders. While these findings are promising, translating them into safe and effective treatments for humans remains a significant challenge.

Telomeres and the Limits of Cell Division

Another central concept in aging biology involves telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes. Each time a cell divides, its telomeres become slightly shorter. When they reach a critical length, the cell can no longer divide and may enter senescence or undergo programmed cell death.

Telomere shortening acts as a biological clock, limiting the number of times a cell can replicate. This mechanism helps prevent uncontrolled cell growth but also contributes to tissue aging. Shortened telomeres are associated with age-related diseases and reduced lifespan in many organisms.

Some cells, such as stem cells and germ cells, maintain their telomeres through an enzyme called telomerase. This has led researchers to explore whether activating telomerase in other cell types could slow or reverse aging. However, telomerase activation carries risks, as excessive telomere maintenance can promote cancer by allowing damaged cells to divide indefinitely. Balancing the benefits and dangers of telomere manipulation remains a critical area of research.

The Role of Epigenetics in Aging

Aging is not driven solely by changes in DNA sequence. Epigenetics, the system of chemical modifications that regulate gene activity without altering the underlying genetic code, plays a crucial role. Over time, epigenetic patterns become increasingly disordered, leading to inappropriate gene expression and cellular dysfunction.

Remarkably, recent research suggests that some aspects of epigenetic aging may be reversible. Experiments in animals have demonstrated that resetting certain epigenetic markers can restore youthful gene expression patterns and improve tissue function. These findings have fueled interest in the possibility of biological rejuvenation.

Epigenetic clocks, which estimate biological age based on patterns of DNA methylation, have provided powerful tools for measuring aging. These clocks reveal that individuals age at different rates and that lifestyle factors, such as diet and stress, can influence biological aging. While epigenetic reprogramming holds promise, its long-term safety and feasibility in humans remain under investigation.

Metabolism, Energy, and the Aging Process

Metabolism lies at the heart of aging. The way cells process energy influences their susceptibility to damage and their ability to repair themselves. One of the most robust findings in longevity research is the link between nutrient sensing and lifespan.

Caloric restriction, defined as reducing calorie intake without malnutrition, has been shown to extend lifespan in many organisms, from yeast to rodents. This effect is thought to arise from changes in metabolic pathways that enhance cellular maintenance and stress resistance. Key molecular players include insulin signaling, mTOR, and AMPK, which regulate growth, energy use, and repair processes.

While long-term caloric restriction is difficult and potentially harmful for humans, researchers are investigating whether drugs can mimic its beneficial effects. Compounds such as rapamycin and metformin have attracted attention for their ability to influence metabolic pathways associated with aging. Clinical trials are ongoing to determine whether these drugs can safely improve healthspan in humans.

Stem Cells and Tissue Regeneration

Stem cells are essential for maintaining and repairing tissues throughout life. With age, stem cell populations decline in number and function, reducing the body’s capacity for regeneration. Muscles weaken, skin heals more slowly, and organs lose resilience.

Enhancing stem cell function is a major focus of regenerative medicine and longevity research. Approaches include stimulating the body’s own stem cells, transplanting stem cells grown in the laboratory, and modifying the tissue environment to support regeneration. While these strategies have shown promise in specific contexts, such as bone marrow transplantation, their application to systemic aging remains limited.

Aging tissues often become hostile environments for stem cells due to inflammation and altered signaling. Addressing these environmental factors may be just as important as targeting the stem cells themselves. This insight underscores the interconnected nature of aging mechanisms.

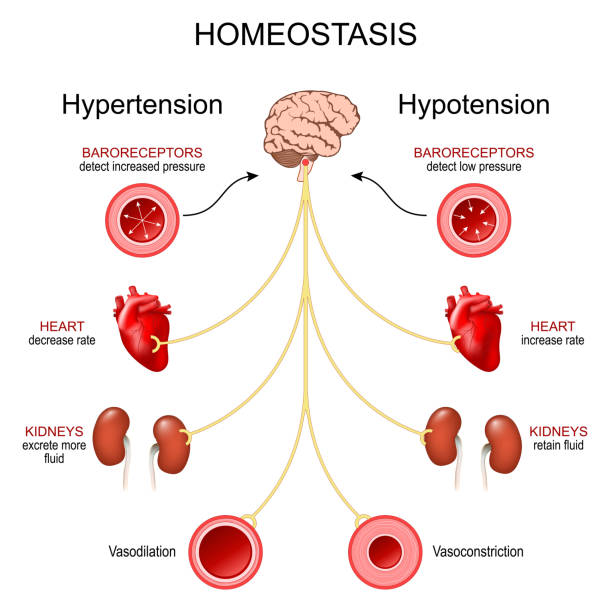

The Immune System and Inflammaging

The immune system undergoes profound changes with age. Its ability to respond to new infections declines, while chronic inflammation increases. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as inflammaging, contributes to many age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and neurodegeneration.

Chronic inflammation arises from multiple sources, including senescent cells, microbial changes in the gut, and lifelong exposure to environmental stressors. Rather than being a single disease, inflammaging represents a systemic imbalance that gradually erodes health.

Longevity research seeks to modulate the immune system to preserve its protective functions while reducing harmful inflammation. Strategies include targeting inflammatory pathways, improving immune cell renewal, and maintaining a healthy microbiome. Achieving this balance is complex, as excessive immune suppression can increase susceptibility to infection and cancer.

The Brain, Aging, and Cognitive Decline

The aging brain presents some of the most feared consequences of growing older. Memory loss, reduced cognitive flexibility, and neurodegenerative diseases profoundly affect quality of life. Understanding brain aging is therefore a central concern in longevity research.

Neurons are long-lived cells that rarely divide, making them particularly vulnerable to accumulated damage. Protein aggregates, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired waste clearance contribute to neuronal decline. The brain’s support cells, including microglia and astrocytes, also change with age, influencing inflammation and synaptic function.

Research has shown that certain aspects of brain aging can be modified. Physical activity, cognitive engagement, and metabolic health all influence brain resilience. At the molecular level, scientists are exploring ways to enhance neuronal repair mechanisms and prevent toxic protein accumulation. While reversing brain aging remains a distant goal, slowing cognitive decline is increasingly plausible.

Can Aging Be Reversed? What the Evidence Really Shows

The idea of reversing aging often evokes images of dramatic rejuvenation, but the scientific reality is more nuanced. In laboratory settings, researchers have achieved partial reversal of age-related changes in cells and animals. These interventions do not make organisms immortal, nor do they restore youth in a simple or complete way.

For example, reprogramming cells to a more youthful state can erase some markers of aging, but excessive reprogramming can erase cell identity and increase cancer risk. Senolytic treatments can improve tissue function, but they do not eliminate all aspects of aging. Metabolic interventions can extend lifespan in animals, but their effects in humans are still being tested.

Current evidence suggests that aging is plastic to some degree, meaning it can be influenced and modified. However, it is not yet clear whether aging can be fully reversed in complex organisms like humans. Most researchers emphasize realistic goals, such as delaying aging, improving healthspan, and reducing the burden of age-related disease.

Ethical and Social Implications of Longevity Science

The prospect of extending human lifespan raises profound ethical questions. Who will have access to longevity interventions? Will they exacerbate existing social inequalities? How will longer lives affect population growth, employment, and intergenerational relationships?

There are also philosophical questions about the meaning of aging and death. Mortality has shaped human culture, creativity, and values throughout history. Extending life could alter how people perceive time, purpose, and responsibility. Some argue that longer lives would allow individuals to contribute more deeply to society, while others worry about stagnation and resource strain.

Ethical frameworks must evolve alongside scientific advances. Responsible longevity research requires not only technical expertise but also thoughtful consideration of its broader consequences. Public engagement and transparent policy discussions will be essential as interventions move closer to clinical reality.

Separating Science from Hype in the Longevity Industry

The growing interest in aging has given rise to a flourishing longevity industry, offering supplements, diets, and therapies that claim to slow or reverse aging. Many of these claims are not supported by rigorous scientific evidence. Distinguishing credible research from marketing hype is a critical challenge.

Science advances through controlled experiments, peer review, and reproducibility. Genuine longevity interventions must demonstrate clear benefits and acceptable risks in well-designed clinical trials. While lifestyle factors such as nutrition, exercise, and sleep undeniably influence aging, no pill or procedure currently offers dramatic rejuvenation.

Skepticism is not cynicism. It is an essential component of scientific integrity. As research progresses, it is vital to communicate findings accurately, acknowledging both their promise and their limitations.

The Future of Longevity Research

Longevity science is still in its early stages, but it is advancing rapidly. Improved tools for measuring biological age, such as epigenetic clocks, allow researchers to assess interventions more precisely. Advances in genomics, artificial intelligence, and systems biology are revealing new connections between aging pathways.

Future progress will likely involve combination approaches that target multiple mechanisms simultaneously. Aging is not a single problem with a single solution. Effective interventions may need to address metabolism, inflammation, cellular damage, and regeneration together.

Clinical translation will require careful testing, long-term studies, and regulatory frameworks designed for interventions that target aging rather than specific diseases. This represents a shift in how medicine conceptualizes health and disease.

What Longevity Science Really Promises

The question of whether science can reverse aging does not have a simple yes or no answer. What science currently promises is not eternal youth, but the possibility of longer, healthier lives. It offers the prospect of reducing suffering, preserving independence, and extending the years of vitality rather than prolonging frailty.

Longevity research reframes aging as a dynamic biological process rather than an unchangeable destiny. It invites a future in which growing older does not necessarily mean growing sicker. While dramatic reversal of aging remains speculative, meaningful delay and partial rejuvenation are increasingly grounded in evidence.

Aging, Meaning, and the Human Story

Aging is not merely a biological process; it is a deeply human experience. It shapes how people understand time, relationships, and identity. Scientific efforts to modify aging do not erase its emotional and cultural significance. Instead, they add a new dimension to an ancient story.

To ask whether science can reverse aging is to ask how much control humans can exert over their own biology. It is a question that blends humility with ambition. Nature is complex, resilient, and often resistant to simple solutions. Yet history shows that understanding can lead to transformation.

Longevity research stands as one of the most ambitious scientific endeavors of our time. It does not promise immortality, but it challenges the assumption that decline is inevitable and immutable. In doing so, it reshapes how humanity thinks about life, health, and the future.