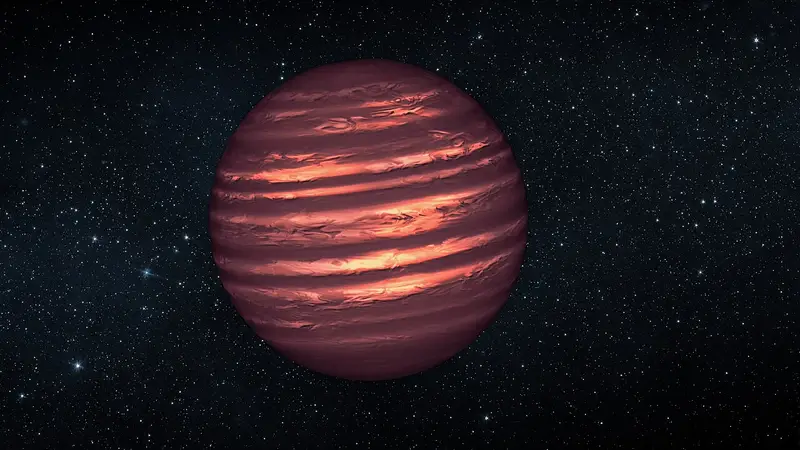

In the vast darkness between the stars, there exist objects that glow faintly, quietly defying the neat categories humans love to impose on the universe. They are not quite stars, yet far more than planets. They are massive enough to burn briefly, but too small to shine forever. Astronomers call them brown dwarfs, and for decades they have challenged our understanding of how stars and planets form, live, and fade.

Brown dwarfs occupy a cosmic middle ground, a twilight realm where definitions become slippery and certainty dissolves. They are often called “failed stars,” but that label, while catchy, does them an injustice. Brown dwarfs are not failures of nature. They are natural outcomes of the same processes that create blazing suns and gentle worlds. Their existence tells a deeper, more nuanced story about how the universe builds objects from gas, dust, gravity, and time.

To understand brown dwarfs is to confront the fact that the universe does not always respect the boundaries we draw. Instead, it offers a continuum, a spectrum of possibilities where stars gradually become planets and planets shade into stars.

The Birth of a Cosmic In-Between

Stars are born in cold, dense clouds of gas and dust scattered throughout galaxies. Under the relentless pull of gravity, these clouds collapse, fragmenting into clumps that grow hotter and denser as they shrink. When a clump becomes massive enough, its core temperature rises until nuclear fusion ignites, and a star is born.

Brown dwarfs begin their lives in much the same way. They form from collapsing clouds of gas, just like stars do. The crucial difference lies in mass. A star needs sufficient mass for its core to reach the temperatures and pressures required to sustain hydrogen fusion, the process that powers stars for millions or billions of years. Brown dwarfs fall short of this critical threshold.

As a collapsing gas cloud destined to become a brown dwarf contracts, its core heats up, but not enough. For a brief period, some brown dwarfs can fuse deuterium, a heavier form of hydrogen, and the most massive among them may even fuse lithium. But these reactions are short-lived. They do not provide a long-term energy source. Eventually, the brown dwarf exhausts its limited nuclear fuel and begins a slow, inexorable cooling.

This incomplete ignition is what gives brown dwarfs their reputation as “failed stars.” Yet from another perspective, they are not failures at all. They are stars that almost were, cosmic near-misses that reveal how finely balanced the processes of star formation truly are.

Mass: The Thin Line Between Stars and Planets

At the heart of the brown dwarf mystery lies mass. Mass determines an object’s fate, its internal structure, and its ultimate destiny. Too little mass, and gravity cannot compress material enough to ignite nuclear fusion. Too much mass, and fusion begins, transforming the object into a true star.

Brown dwarfs occupy a narrow but significant mass range between the heaviest planets and the lightest stars. They are more massive than gas giants like Jupiter but less massive than the smallest red dwarf stars. This overlap creates a profound ambiguity. Some objects have masses comparable to giant planets, yet they formed like stars. Others resemble stars in composition but behave thermally like planets.

This mass-based definition reveals a fundamental tension in astronomy. Is an object defined by what it is made of, how massive it is, or how it formed? Brown dwarfs force astronomers to confront these questions head-on, exposing the limitations of simple labels.

Heat Without Fire: The Inner Lives of Brown Dwarfs

Unlike stars, which generate energy through sustained nuclear fusion, brown dwarfs shine primarily through leftover heat from their formation. When a brown dwarf forms, gravitational contraction releases energy, heating its interior to extreme temperatures. This initial heat causes the object to glow, often in infrared wavelengths invisible to the human eye.

Over time, however, that heat slowly radiates away into space. With no ongoing fusion to replenish it, the brown dwarf cools, dims, and fades. Young brown dwarfs can be relatively warm and luminous compared to their older counterparts, which may become so cool and faint that detecting them becomes extraordinarily difficult.

Inside a brown dwarf, matter exists under exotic conditions. Immense pressures compress hydrogen into a dense, metallic state, where electrons move freely, conducting electricity. This structure resembles that of giant planets like Jupiter more than it does a star like the Sun, further blurring the boundary between stellar and planetary physics.

A Rainbow of Subtypes

As brown dwarfs cool over time, their atmospheres undergo dramatic changes. Different molecules form and condense at different temperatures, giving rise to a rich variety of spectral characteristics. Astronomers classify brown dwarfs into distinct spectral types based on the features observed in their light.

The warmest brown dwarfs exhibit features associated with metal oxides and silicate clouds, while cooler ones show strong absorption from methane and water vapor. The coldest known brown dwarfs approach temperatures comparable to Earth’s polar regions, hosting complex atmospheric chemistry that challenges our understanding of cloud formation and molecular physics.

These spectral classes represent a cooling sequence, a kind of evolutionary path. A single brown dwarf may pass through several spectral stages over billions of years, transforming its appearance as it ages. In this sense, brown dwarfs are time travelers, carrying within them a record of their thermal history.

The Challenge of Detection

For much of astronomical history, brown dwarfs remained hidden. They emit little visible light and do not shine steadily like stars. Detecting them requires sensitive instruments capable of observing infrared radiation, where these cool objects are brightest.

The first confirmed brown dwarfs were discovered only in the late twentieth century, despite decades of theoretical predictions. Their discovery was a triumph of both technology and persistence, opening a new window onto the low-mass end of star formation.

Even today, brown dwarfs are elusive. Many wander alone through space, unbound to any star. Others orbit stars at great distances, making them difficult to distinguish from massive planets. Their faintness means that astronomers must search carefully, often relying on subtle motions, spectral fingerprints, or gravitational effects to reveal their presence.

Brown Dwarfs and Giant Planets: A Blurred Boundary

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of brown dwarfs is how closely they resemble giant planets in certain respects. Both are dominated by hydrogen and helium. Both lack sustained hydrogen fusion. Both can have complex atmospheres with clouds, storms, and dynamic weather systems.

Yet their origins often differ. Giant planets typically form within disks of gas and dust surrounding young stars, growing through the accumulation of material. Brown dwarfs, by contrast, usually form through direct gravitational collapse, like stars. This difference in formation history is subtle but profound, shaping their internal structures and chemical compositions.

In practice, however, nature does not always follow clean rules. Some objects blur even this distinction, forming in disks yet reaching masses typical of brown dwarfs, or collapsing like stars but remaining barely more massive than planets. These ambiguous cases challenge astronomers to rethink how they classify celestial bodies.

Atmospheres of Mystery and Motion

The atmospheres of brown dwarfs are among the most intriguing environments in astrophysics. Despite their relatively small sizes, they host complex weather patterns driven by rapid rotation, strong winds, and evolving cloud layers.

Observations reveal variability in their brightness, suggesting swirling clouds of silicates, iron, and other exotic materials. These clouds can form, dissipate, and shift over time, creating atmospheric dynamics reminiscent of Jupiter’s belts and storms, but under far more extreme conditions.

Studying brown dwarf atmospheres offers a unique opportunity. Because they are isolated objects, free from the glare of a nearby star, their atmospheric spectra can be observed directly. This makes them valuable analogs for studying the atmospheres of giant exoplanets, which are often much harder to observe in detail.

Companions and Loners

Brown dwarfs can exist in a variety of configurations. Some orbit stars as distant companions, while others form binary systems with fellow brown dwarfs. Many drift alone through interstellar space, unattached to any stellar host.

These solitary brown dwarfs are particularly evocative. Born in stellar nurseries but ejected through gravitational interactions, they wander the galaxy as cosmic nomads, carrying the imprint of their birthplaces but destined never to orbit a star. Their existence suggests that star formation is a chaotic process, capable of producing not only orderly systems but also vast populations of orphaned objects.

Brown Dwarfs in the Galactic Population

Although individually faint, brown dwarfs may be numerous. Estimates suggest that they could rival stars in sheer numbers within the Milky Way. If so, they represent a significant component of the galaxy’s mass and structure.

Their abundance has implications for understanding how efficiently stars form and how mass is distributed in galaxies. Brown dwarfs also contribute to the faint background glow of infrared light, subtly shaping the galaxy’s overall emission.

By studying brown dwarfs, astronomers gain insight into the full range of outcomes produced by star formation, from massive luminous stars to dim, cooling substellar objects.

The Role of Brown Dwarfs in Planetary Science

Brown dwarfs have become unexpectedly important to planetary science. Their atmospheres provide natural laboratories for studying chemical reactions, cloud physics, and heat transport under conditions difficult to replicate elsewhere.

Because brown dwarfs cool over time, they pass through temperature regimes similar to those of giant exoplanets at different stages of their evolution. By observing brown dwarfs of various ages and temperatures, scientists can piece together how planetary atmospheres might change over billions of years.

In this way, brown dwarfs serve as bridges between stellar astrophysics and planetary science, linking two fields that were once considered largely separate.

A Test of Theories

Brown dwarfs also serve as stringent tests for theoretical models. Predicting how these objects evolve requires understanding complex physics, including degeneracy pressure, molecular opacities, and cloud formation.

Their interiors are supported not by thermal pressure alone but by quantum mechanical effects that arise when electrons are forced into close proximity. This degeneracy pressure halts further contraction, preventing brown dwarfs from collapsing into smaller objects even as they cool.

Matching observations to theory is challenging, but each success strengthens confidence in our understanding of matter under extreme conditions. Each discrepancy reveals gaps in knowledge, driving further investigation.

Cultural and Philosophical Resonance

Beyond their scientific importance, brown dwarfs carry a subtle philosophical weight. They remind us that nature does not conform to human categories. The universe is not divided into clean boxes labeled “star” and “planet,” but instead presents a continuum shaped by probability and circumstance.

The term “failed star” reflects a human tendency to judge natural objects by their resemblance to familiar ideals. Yet brown dwarfs are not failures; they are expressions of the same cosmic processes that gave rise to the Sun, Earth, and life itself. They embody the idea that variation is not error but richness.

In their quiet glow and gradual fading, brown dwarfs evoke a sense of cosmic melancholy. They are born hot and bright, only to cool and darken over time, mirroring in some ways the finite arcs of stars, planets, and even living beings.

The Future of Brown Dwarf Research

As technology advances, the study of brown dwarfs is entering a new era. More sensitive infrared telescopes are revealing ever cooler and fainter objects, pushing the boundaries of what can be detected. Detailed spectra are uncovering the complexity of their atmospheres with unprecedented clarity.

Future observations may identify objects even colder than those currently known, further narrowing the gap between brown dwarfs and giant planets. At the same time, surveys of star-forming regions will shed light on how frequently brown dwarfs form and under what conditions.

These discoveries will not only deepen our understanding of brown dwarfs themselves but also refine broader theories of star and planet formation.

Brown Dwarfs and the Story of the Universe

In the grand narrative of the cosmos, brown dwarfs occupy a quiet but meaningful chapter. They are reminders that creation is not always dramatic, that some of the universe’s most important lessons are written in faint light and subtle signals.

They tell us that the processes shaping the universe are continuous, not discrete, and that understanding often lies in the gray areas rather than the extremes. By studying brown dwarfs, we learn to appreciate complexity, ambiguity, and the beauty of near-misses.

Brown dwarfs blur the line between planets and stars, not as a flaw in our classifications, but as an invitation to see the universe as it truly is: a place where nature experiments endlessly, producing objects that challenge our expectations and expand our sense of what is possible.

In their dim glow, brown dwarfs whisper a profound truth. The universe is richer than our definitions, more subtle than our categories, and far more imaginative than we ever expected.