Bipolar disorder is often described as a storm within the mind—an unpredictable cycle of highs and lows that can sweep someone from euphoria to despair, from boundless energy to crushing exhaustion. It is not simply “mood swings,” as it is sometimes misunderstood, but a profound and complex mental health condition that affects millions worldwide. Living with bipolar disorder can feel like riding a roller coaster with no control over its speed or direction. One day, the world may glow with infinite possibility, and the next, the same world feels unbearably heavy and hopeless.

Yet, despite its challenges, bipolar disorder is not a life sentence of chaos. With proper understanding, diagnosis, and treatment, individuals can live fulfilling, productive, and meaningful lives. To truly grasp what bipolar disorder is, one must journey into its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatments—exploring the scientific truths and human experiences that shape this condition.

What is Bipolar Disorder?

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mental health condition characterized by extreme shifts in mood, energy, and activity levels. These shifts are not the ordinary ups and downs of daily life. Instead, they represent profound changes in brain function, producing episodes of mania or hypomania on one end, and depression on the other.

Mania can feel like being supercharged with energy—thoughts race, creativity surges, sleep feels unnecessary, and confidence soars to unrealistic levels. Hypomania is a milder form, still marked by increased energy and activity, but less disruptive. Depression, in contrast, brings deep sadness, fatigue, loss of interest, and sometimes even thoughts of death or suicide.

There are different types of bipolar disorder:

- Bipolar I disorder: Defined by manic episodes lasting at least seven days or severe enough to require hospitalization, often alternating with depressive episodes.

- Bipolar II disorder: Involves hypomanic episodes and depressive episodes, but not the full-blown mania seen in Bipolar I.

- Cyclothymic disorder (cyclothymia): A milder, chronic form where symptoms of hypomania and depression occur for years but do not meet the full criteria of major episodes.

Understanding these forms helps explain why bipolar disorder can look different from one person to another.

The Human Face of Bipolar Disorder

Behind the medical definitions lie lived experiences. Someone in a manic episode may feel invincible, plunging into risky behaviors—reckless spending, unsafe sex, or impulsive decisions—believing nothing can go wrong. Another may channel that energy into bursts of productivity, creating art, writing, or work at extraordinary speeds. Yet mania’s crash into depression can be devastating, leaving the person bewildered at how their world has changed overnight.

Families and friends also feel the impact. They may struggle to understand why their loved one alternates between extremes, feeling helpless in the face of sudden changes. Stigma can add another layer of suffering, as society often misunderstands or judges those living with the condition. Recognizing bipolar disorder as a medical condition, not a character flaw, is essential for compassion and effective support.

Causes of Bipolar Disorder

The exact cause of bipolar disorder is still not fully understood, but research reveals it is shaped by a complex interplay of biology, genetics, and environment.

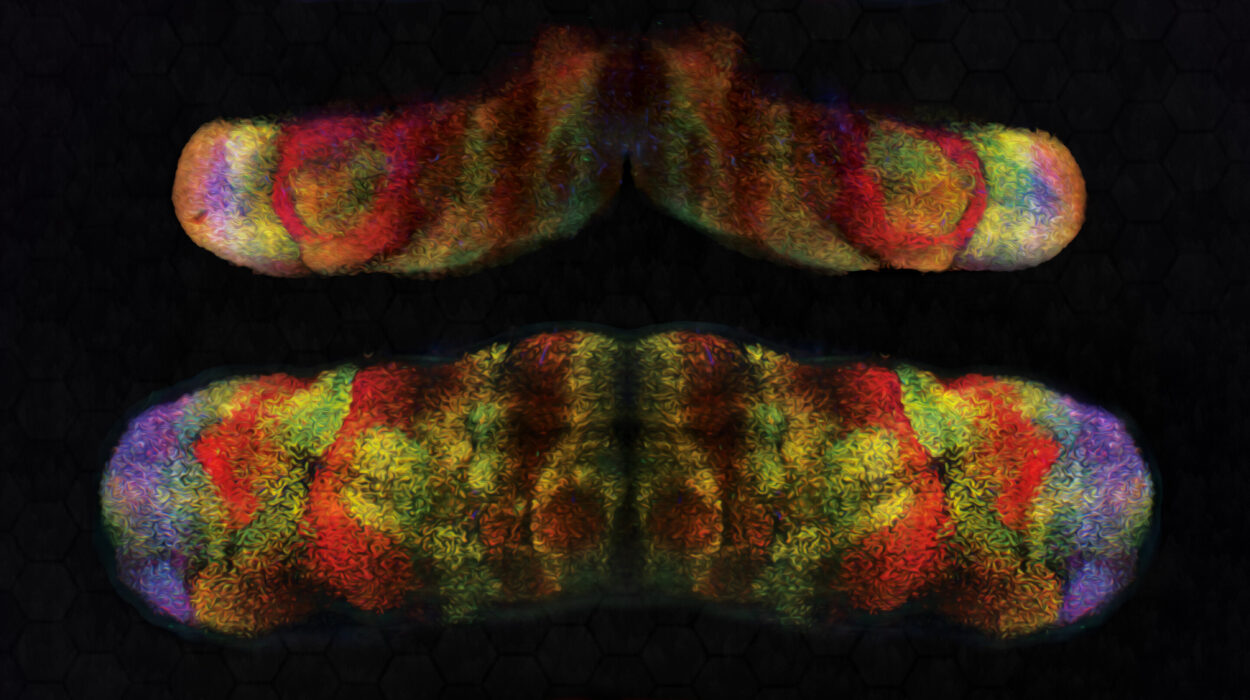

Genetic Factors

Bipolar disorder tends to run in families. If a parent or sibling has the condition, the risk of developing it increases, though it does not guarantee it. Twin studies reveal strong heritability, suggesting that certain genes may predispose individuals to bipolar disorder. However, no single “bipolar gene” has been found—it is likely the result of many genes interacting with life experiences.

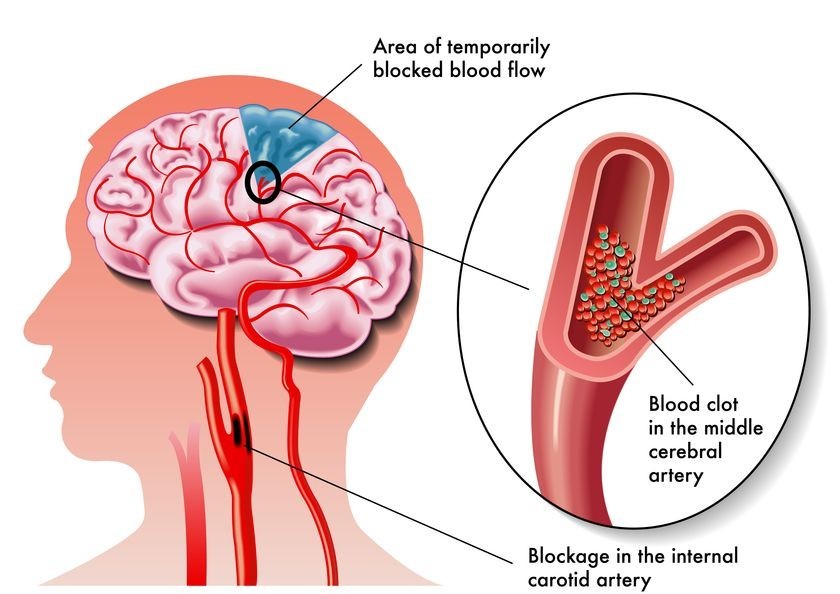

Brain Structure and Chemistry

Brain imaging studies show differences in the structure and function of the brains of people with bipolar disorder. Regions involved in emotion regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus, may function differently. Neurotransmitters—chemical messengers like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine—are also implicated. Disruptions in their balance may contribute to mood swings, with excessive dopamine linked to mania and reduced levels tied to depression.

Environmental Triggers

Genes may load the gun, but environment often pulls the trigger. Stressful life events—trauma, loss, abuse, or major transitions—can trigger episodes in those predisposed to bipolar disorder. Substance abuse, irregular sleep patterns, or chronic stress may also worsen symptoms. Importantly, while these factors influence the condition, they do not cause it alone.

Circadian Rhythm Disruption

Research increasingly shows that disruptions in circadian rhythms—the body’s natural sleep-wake cycles—play a role in bipolar disorder. Many individuals with the condition experience irregular sleep, and changes in daily rhythms often precede manic or depressive episodes. This connection helps explain why stabilizing routines is so important in treatment.

Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder

The symptoms of bipolar disorder manifest in two primary poles—mania/hypomania and depression—though mixed states, where features of both occur simultaneously, are also possible.

Symptoms of Mania

- Increased energy, activity, or restlessness

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep

- Racing thoughts and rapid speech

- Distractibility

- Risky or impulsive behaviors (spending sprees, sexual indiscretions, reckless driving)

- Extreme irritability or euphoria

Mania can be intoxicating at first but quickly spirals into dangerous territory, disrupting relationships, finances, and health.

Symptoms of Hypomania

Hypomania is similar to mania but less severe. Individuals may feel unusually energetic, productive, or creative, and the symptoms may not cause major impairment. However, hypomania often escalates into full mania or drops into depression.

Symptoms of Depression

- Persistent sadness, emptiness, or hopelessness

- Loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Sleep disturbances (too much or too little)

- Changes in appetite or weight

- Difficulty concentrating, making decisions, or remembering

- Feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- Thoughts of death or suicide

These episodes can last weeks or months, leaving individuals unable to function in their daily lives.

Mixed Episodes

Sometimes symptoms of mania and depression occur together—such as racing thoughts with overwhelming despair. These mixed episodes can be particularly dangerous because the combination of impulsivity and suicidal thinking increases the risk of self-harm.

Diagnosing Bipolar Disorder

Diagnosis is a careful process, as bipolar disorder can resemble other conditions like major depression, anxiety disorders, ADHD, or borderline personality disorder. Misdiagnosis is common, especially when individuals first present with depression, since manic episodes may come later or be overlooked.

Clinical Assessment

Mental health professionals rely on structured interviews, patient history, and input from family members. They ask about mood patterns, energy levels, sleep habits, and behavior changes. Understanding the duration, severity, and frequency of episodes is crucial.

Diagnostic Criteria

According to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), diagnosis requires at least one manic or hypomanic episode for Bipolar I and II, respectively, usually accompanied by depressive episodes. The episodes must cause significant distress or impairment in functioning.

Medical Tests

While no blood test or brain scan can diagnose bipolar disorder directly, doctors may order tests to rule out conditions such as thyroid problems, neurological disorders, or substance use that can mimic mood symptoms.

Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder has no cure, but effective treatment can stabilize mood, reduce symptoms, and improve quality of life. Treatment often combines medication, psychotherapy, lifestyle changes, and social support.

Medication

- Mood stabilizers (such as lithium) are the cornerstone of treatment, helping to prevent manic and depressive episodes. Lithium, one of the oldest treatments, remains highly effective but requires monitoring for side effects.

- Antipsychotics are used for acute mania or mixed episodes and may be used long-term if mood stabilizers are insufficient.

- Antidepressants may be used cautiously for depressive episodes, usually alongside a mood stabilizer to avoid triggering mania.

- Anticonvulsants (like valproate and lamotrigine) are also used as mood stabilizers.

Medication management requires careful monitoring, as side effects can be challenging and adherence is critical to success.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy provides tools to manage symptoms and improve daily functioning. Evidence-based approaches include:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT): Helps individuals identify and challenge negative thoughts, manage stress, and develop coping strategies.

- Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT): Focuses on stabilizing daily routines, particularly sleep and activity cycles, to prevent mood swings.

- Family-focused therapy: Involves family members in treatment to improve communication, reduce conflict, and build support.

Lifestyle and Self-Management

- Regular sleep, exercise, and balanced nutrition help stabilize mood.

- Avoiding alcohol and drugs is crucial, as they can trigger episodes.

- Keeping a mood journal helps track triggers and early warning signs of episodes.

- Mindfulness practices and stress reduction techniques can improve resilience.

Hospitalization and Crisis Care

In severe cases, hospitalization may be necessary to ensure safety, particularly during mania with dangerous behaviors or depression with suicidal risk. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be considered for treatment-resistant cases, particularly severe depression.

Living With Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is not just a medical condition; it is a lived reality. Managing it requires resilience, patience, and support. Many people with bipolar disorder achieve stability and thrive, becoming leaders, artists, scientists, or parents. Famous individuals like Vincent van Gogh, Virginia Woolf, and modern-day creatives have brought attention to the condition, highlighting the complex relationship between mental illness and human creativity.

Support from loved ones is essential. Families and friends can learn about the condition, practice patience, and provide encouragement. Peer support groups also offer a sense of community, breaking the isolation that often accompanies the disorder.

Breaking the Stigma

Stigma remains one of the greatest challenges for people living with bipolar disorder. Misconceptions—that they are “unstable,” “dangerous,” or “incapable”—can prevent individuals from seeking help or being accepted. Public awareness, education, and open conversations are vital to dismantle these myths and replace them with understanding.

The Future of Bipolar Disorder Research

Science continues to uncover the mysteries of bipolar disorder. Advances in genetics, brain imaging, and neurobiology promise more precise diagnosis and personalized treatments. Digital tools like smartphone apps that monitor sleep, speech patterns, or activity may one day predict episodes before they occur, giving individuals greater control over their health.

Researchers are also exploring new medications and therapies, from glutamate-modulating drugs to brain stimulation techniques, offering hope for those who do not respond to current treatments.

A Journey Toward Stability and Hope

Bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, but it is not a life without hope. With the right combination of treatment, lifestyle adjustments, and support, individuals can live full, meaningful lives. The storm may never disappear completely, but it can be navigated—managed with skill, courage, and care.

Health is not the absence of struggle, but the ability to move forward despite it. For those with bipolar disorder, every step toward balance, every day of stability, and every connection with understanding others is a triumph.