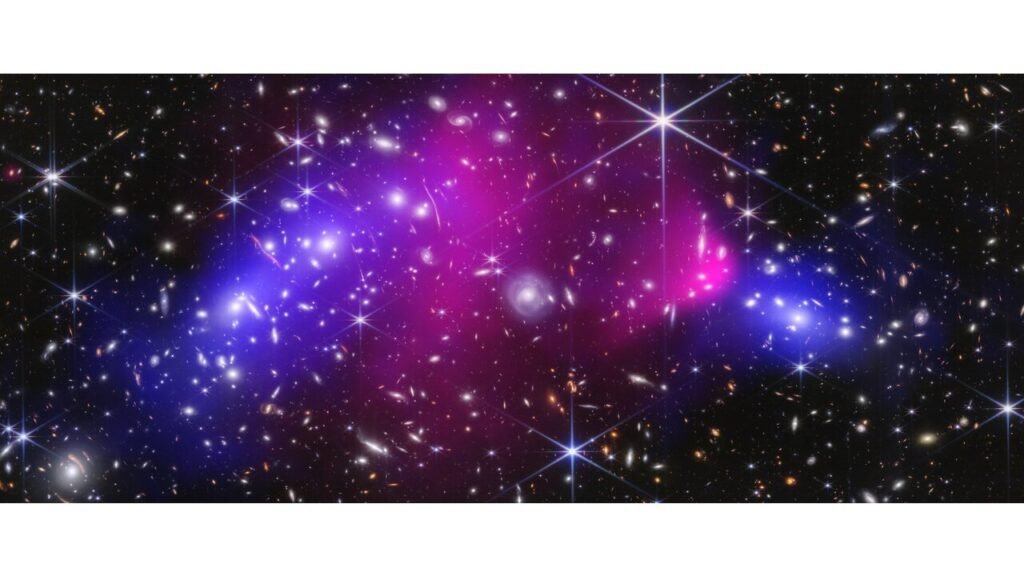

In a distant corner of the universe, two colossal clusters of galaxies slammed into each other billions of years ago in a cosmic car crash so violent that it sent ripples through the fabric of space. Now, the James Webb Space Telescope has turned its powerful gaze on the aftermath of that crash—the famous Bullet Cluster—and revealed secrets hidden from human eyes until this very moment.

Peering deeper than ever before, Webb’s near-infrared vision has brought into sharp focus an extraordinary bounty of faint, far-flung galaxies—and, crucially, offered scientists their clearest map yet of something even more elusive: dark matter.

A Cosmic Collision Frozen in Time

The Bullet Cluster is not just an astronomical curiosity—it’s one of the most dramatic and telling sights in the cosmos. Located in the Carina constellation, some 3.8 billion light-years from Earth, it’s a scene frozen in cosmic time, capturing two galaxy clusters mid-collision. Galaxies, each containing billions of stars, have sailed past one another, but their clouds of scorching hot gas collided like waves crashing into rocks, creating the iconic “bullet” shape blazing in X-ray images.

Yet amid this colossal chaos lies an even bigger mystery: invisible matter that outweighs everything we can see. Dark matter does not glow, absorb, or reflect light. But it exerts gravity, bending the light of galaxies far behind the Bullet Cluster like a cosmic magnifying glass—a phenomenon astronomers call gravitational lensing.

This is where Webb enters the story.

The Lens That Sees the Invisible

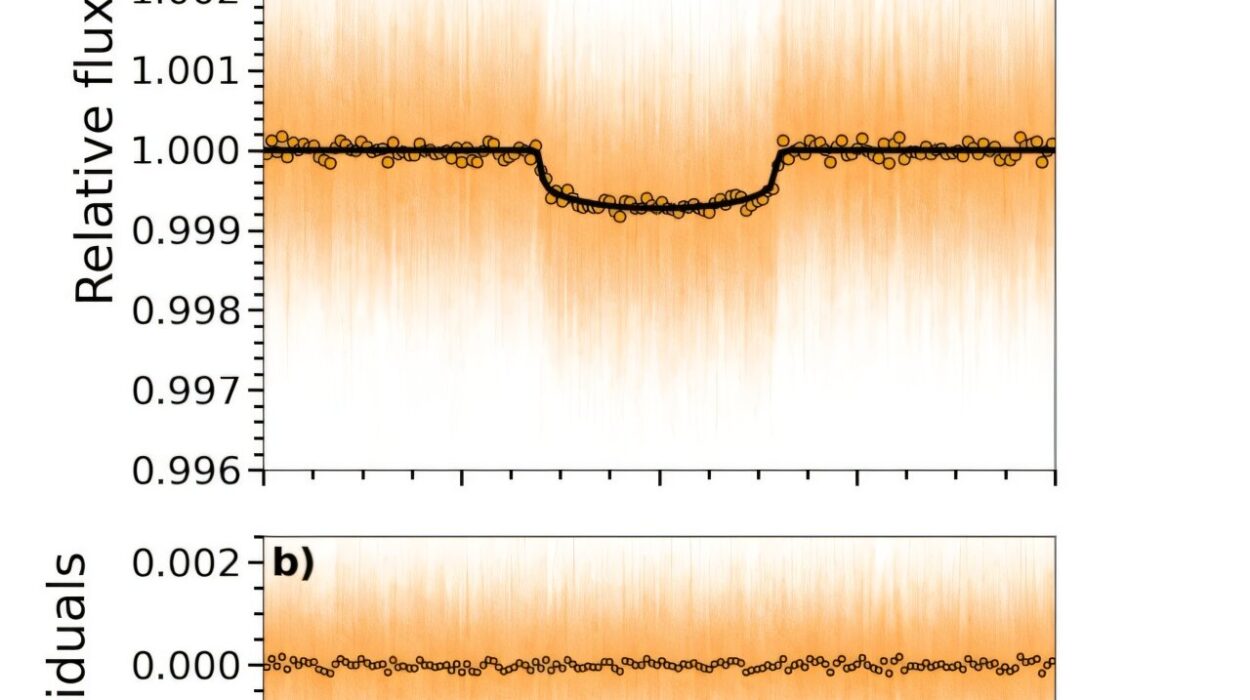

With its crisp infrared eyes, Webb has captured an unprecedented view of the Bullet Cluster, revealing thousands of tiny, distant galaxies strewn across the cosmic canvas. But it’s not just the stunning imagery that has scientists buzzing—it’s what those images allow them to measure.

“Webb’s observations dramatically improve what we can measure in this scene—including pinpointing the position of invisible particles known as dark matter,” said Kyle Finner, assistant scientist at Caltech’s IPAC in Pasadena, California.

Leading the charge is Sangjun Cha, a Ph.D. student at Yonsei University in Seoul, South Korea, who spearheaded the new research published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. “With Webb’s observations, we carefully measured the mass of the Bullet Cluster with the largest lensing dataset to date, from the galaxy clusters’ cores all the way out to their outskirts,” Cha explained.

Earlier studies of the Bullet Cluster relied on significantly fewer lensing observations, resulting in rougher estimates of how mass—including dark matter—is spread across the colliding clusters. Webb’s new images have changed that landscape entirely.

The Ripples of a Hidden Sea

Mapping dark matter is a bit like trying to chart the currents of a transparent ocean. To explain it, astronomer James Jee, co-author of the study and professor at Yonsei University and UC Davis, offers a vivid analogy:

“Think of a pond filled with clear water and pebbles,” he said. “You cannot see the water unless there’s wind, which causes ripples. Those ripples distort the shapes of the pebbles below, causing the water to act like a lens.”

In the cosmos, dark matter is the invisible water, while background galaxies are the pebbles. As dark matter’s gravitational pull warps space, it distorts the light from those background galaxies into stretched arcs and strange shapes. By carefully measuring these distortions in Webb’s images, astronomers can draw invisible maps of dark matter’s distribution—maps that would otherwise be utterly impossible.

And the maps tell a remarkable tale.

Ghostly Stars Lighting Up the Dark

The new study has confirmed something that’s tantalized astronomers for years: the presence of intracluster light—faint glow emitted by stars no longer bound to any single galaxy. These stars drift freely between galaxies, orphaned by the violent collision.

“We confirmed that the intracluster light can be a reliable tracer of dark matter, even in a highly dynamic environment like the Bullet Cluster,” said Cha. In other words, these lonely stars seem to follow the dark matter’s invisible contours.

This could be a game-changer. If astronomers can use intracluster stars as a kind of cosmic paintbrush to trace dark matter’s shape, it might become easier to map the invisible scaffolding that underpins the universe.

The Dark Matter Enigma Deepens

While the Bullet Cluster has long been a poster child for dark matter, Webb’s data brings crucial new insights. In past collisions, scientists wondered: could dark matter particles bump into each other and interact, just as normal matter does? If so, it might leave clues—an offset between where galaxies sit and where dark matter congregates.

Webb’s observations show no such offset.

“As the galaxy clusters collided, their gas was dragged out and left behind, which the X-rays confirm,” said Finner. “Webb’s observations show that dark matter still lines up with the galaxies—and was not dragged away.”

This bolsters the idea that dark matter is aloof, passing through itself and everything else without noticeable friction. It remains eerily invisible and indifferent—its presence betrayed only by gravity’s tug.

A Cosmic Crime Scene with Clues Yet to Solve

Yet the story isn’t as simple as two clusters smashing together once and drifting apart. Webb’s sharp eye has revealed odd lumps and elongated streaks of mass in one of the clusters—a sign that the Bullet Cluster’s history may be more complicated than anyone guessed.

“The larger cluster, which now sits on the left, might have suffered a minor collision before it rammed through the galaxy cluster now at right,” said Jee. “The same larger cluster may also have experienced a violent interaction afterward, causing an additional shake up of its contents.”

It’s a cosmic crime scene with clues scattered across billions of light-years, hinting at multiple collisions over time. Untangling this saga will take more than images—it will demand powerful simulations and future observations.

The Giant Yet to Be Revealed

Even with Webb’s mighty vision, the full story isn’t entirely in view. The telescope’s NIRCam captured a significant slice of the Bullet Cluster, but not its entire span. “It’s like looking at the head of a giant,” Jee said. “Webb’s initial images allow us to extrapolate how heavy the whole ‘giant’ is, but we’ll need future observations of the giant’s whole ‘body’ for precise measurements.”

That’s where the future shines bright. NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, set to launch by 2027, will capture sweeping near-infrared images across vast regions of sky. Together with Webb’s precise focus, Roman’s broader view promises a full portrait of the Bullet Cluster—and perhaps a way to replay its cosmic collisions in computer simulations, step by step.

“With Roman, we will have complete mass estimates of the entire Bullet Cluster, which would allow us to recreate the actual collision on computers,” said Finner.

Unraveling the Invisible Universe

From a simple magnetic compass that fascinated a young Albert Einstein to a telescope parked a million miles from Earth, humanity’s tools for understanding gravity and light have come a long way. And yet, in the Bullet Cluster, the universe reminds us that most of what exists remains unseen.

Thanks to Webb’s latest observations, the cosmos has yielded new clues—but not final answers. Dark matter’s true nature still slips through our fingers like cosmic mist. Each discovery only deepens the mystery and beckons us to look further, to see what lies beyond.

Because in places like the Bullet Cluster, the universe whispers a timeless truth: there’s always more to the story.

Reference: Sangjun Cha et al, A High-Caliber View of the Bullet Cluster through JWST Strong and Weak Lensing Analyses, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/add2f0