High up in the thin, crisp air where mountains scrape the sky, animals have evolved countless extraordinary tricks to survive. But a new study suggests that life at altitude may come at an unexpected cost: the ancient gift of smell.

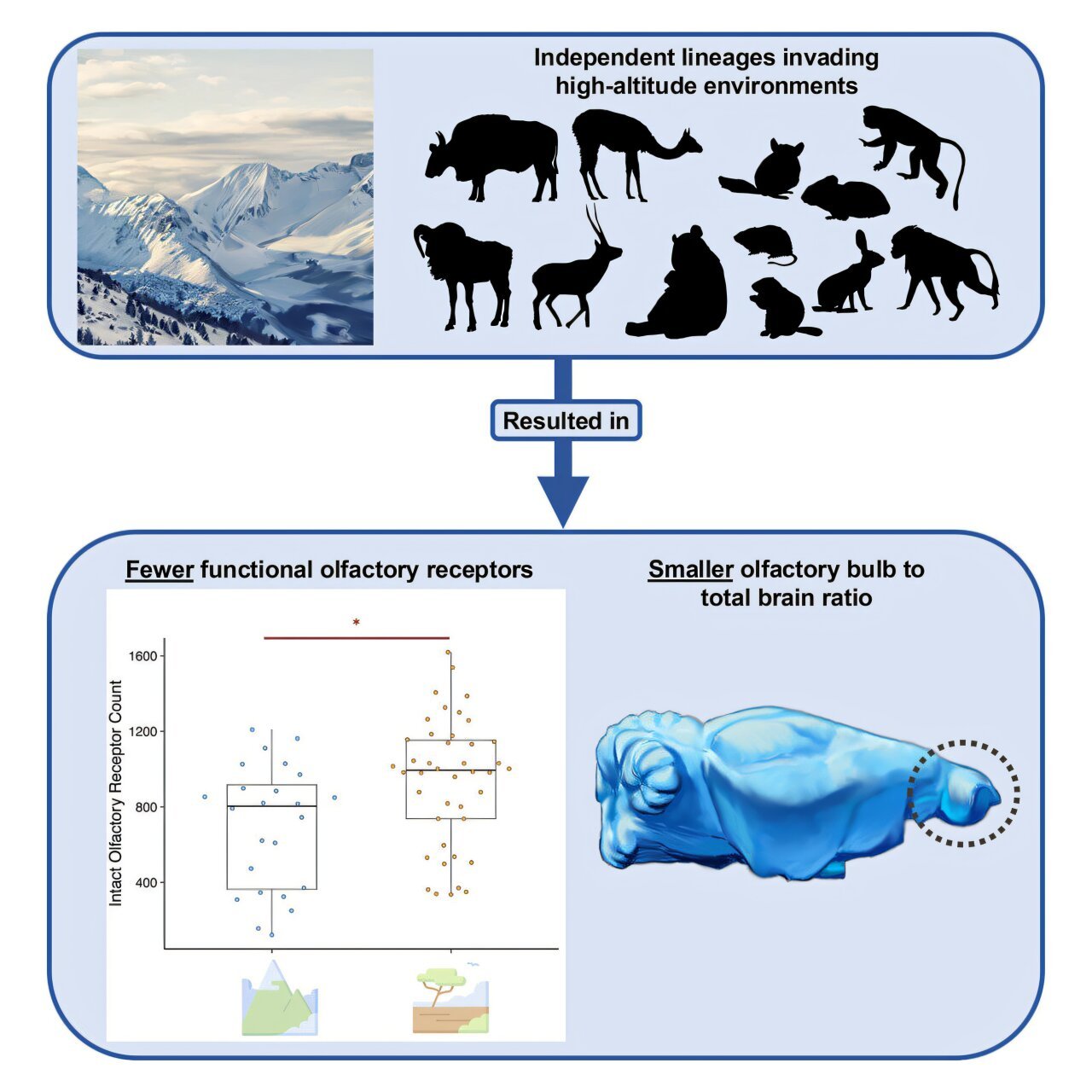

A paper published this week in Current Biology reveals that mammals living at elevations above 1,000 meters have significantly fewer genes tied to scent detection—and smaller smell-processing centers in their brains—than their lowland relatives. From monkeys perched in misty mountain canopies to nimble goats leaping across rocky cliffs, these creatures appear to be trading away their noses in the name of survival.

“This isn’t just about gaining new abilities to handle the cold or the thin air,” said Dr. Li Zhang, evolutionary biologist and lead author of the study. “Sometimes evolution means losing things. In this case, it seems animals are giving up a good chunk of their sense of smell.”

A Genomic Dive Into Mountain Life

To uncover this hidden twist in high-altitude evolution, the researchers screened the genomes of 27 species spanning a dazzling range of mammalian life. They examined both domesticated and wild animals: monkeys swinging through Himalayan forests, llamas grazing Andean slopes, goats scaling Alpine crags, and even humble guinea pigs adapted to life above the clouds.

The genetic findings were striking. High-altitude animals showed an average 23% reduction in genes dedicated to olfaction—the sense of smell—compared to their lowland kin. In anatomical terms, the olfactory bulb, a critical brain center for processing smells, shrank by about 18% on average.

But intriguingly, these losses were specific. Genes tied to pheromone detection (used in mating and social signaling) and taste appeared untouched.

“It’s like nature has chosen to trim away one sense, while leaving others intact,” Dr. Zhang explained. “This kind of selective loss tells us a lot about how animals adapt—or maladapt—to extreme environments.”

The Mountain Air: Beautiful, Breathless, and Scentless

Why would life at high altitudes erode an animal’s sense of smell? The answer lies partly in the rarefied mountain air.

At higher elevations, the atmosphere is thinner, colder, and far drier. Scent molecules—the invisible chemical whispers animals rely on to find food, detect predators, and communicate—struggle to travel through such conditions. It’s like trying to smell flowers in a room with all the windows open during a blizzard: the scents simply blow away.

Moreover, thin air and freezing temperatures often cause nasal congestion and inflammation. For creatures living year-round in these harsh conditions, chronic stuffy noses might make sniffing out scents almost impossible.

“If there’s nothing left to smell, or if your nose is constantly blocked, then having a powerful sense of smell might become useless—or even a waste of biological resources,” Dr. Zhang said.

Losing Smell, Gaining Something Else?

Yet the story might not end with a dulled nose. Evolution is rarely one-sided. Researchers suspect that mountain-dwelling mammals may be compensating for their diminished olfactory powers by sharpening other senses, like vision or hearing.

“A goat that can’t smell as well might need to spot predators from further away,” Dr. Zhang noted. “Or a monkey in the mountains might rely more on sight and sound to locate food or recognize friends.”

At this stage, such ideas remain hypotheses. The study didn’t directly measure enhancements in other senses. But it opens a tantalizing question: has the sacrifice of smell helped unlock other evolutionary superpowers in the highlands?

Humans Defy the Trend—for Now

In a fascinating twist, the researchers extended their genomic sleuthing to humans. They compared the DNA of Tibetans—whose ancestors have lived above 3,000 meters for thousands of years—with the low-altitude Han Chinese population. Despite the challenging mountain air, they found no significant genetic changes linked to smell in Tibetans.

Why might humans buck the trend?

Scientists suggest two possible reasons. First, highland and lowland human populations have mixed throughout history, potentially diluting any genetic changes tied to olfaction. Second, there simply may not have been enough time—or enough generations—for such genetic shifts to appear.

“Humans are complicated,” Dr. Zhang said with a smile. “We’re mobile, we migrate, we intermarry. That makes our genetic story different from animals that are isolated in specific habitats.”

A New Chapter in Evolutionary Biology

This study doesn’t just reveal a quirk of mountain life; it adds a fresh layer to our understanding of evolution itself. Until now, scientists have mostly focused on how species gain new abilities to survive in extreme environments—thicker fur, higher red blood cell counts, better cold tolerance.

But this research highlights that evolution can also work through loss—an idea known as maladaptation. In some situations, shedding certain traits may be just as crucial as acquiring new ones.

“It’s a shift in how we think,” Dr. Zhang reflected. “Loss can be a form of adaptation. Evolution is not always about getting better at everything—it’s about getting better at the things that matter most in a given environment.”

Scent of Future Discoveries

The implications of this research ripple far beyond mountain meadows. Understanding how certain traits fade away could help explain genetic diseases, sensory disorders, or even how our own species might adapt—or maladapt—to changing climates.

It also raises poignant questions about what animals lose in the invisible trade-offs of evolution. A goat that can’t smell its way through mountain winds may be better equipped to live at altitude—but does it lose a piece of the sensory world that once shaped its ancestors’ lives?

As scientists continue to climb the genomic peaks of evolutionary biology, one thing is clear: in the mountains, survival may depend not only on what you gain—but also on what you’re willing to leave behind.

Reference: Allie M. Graham et al, Convergent reduction of olfactory genes and olfactory bulb size in mammalian species at altitude, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.05.061