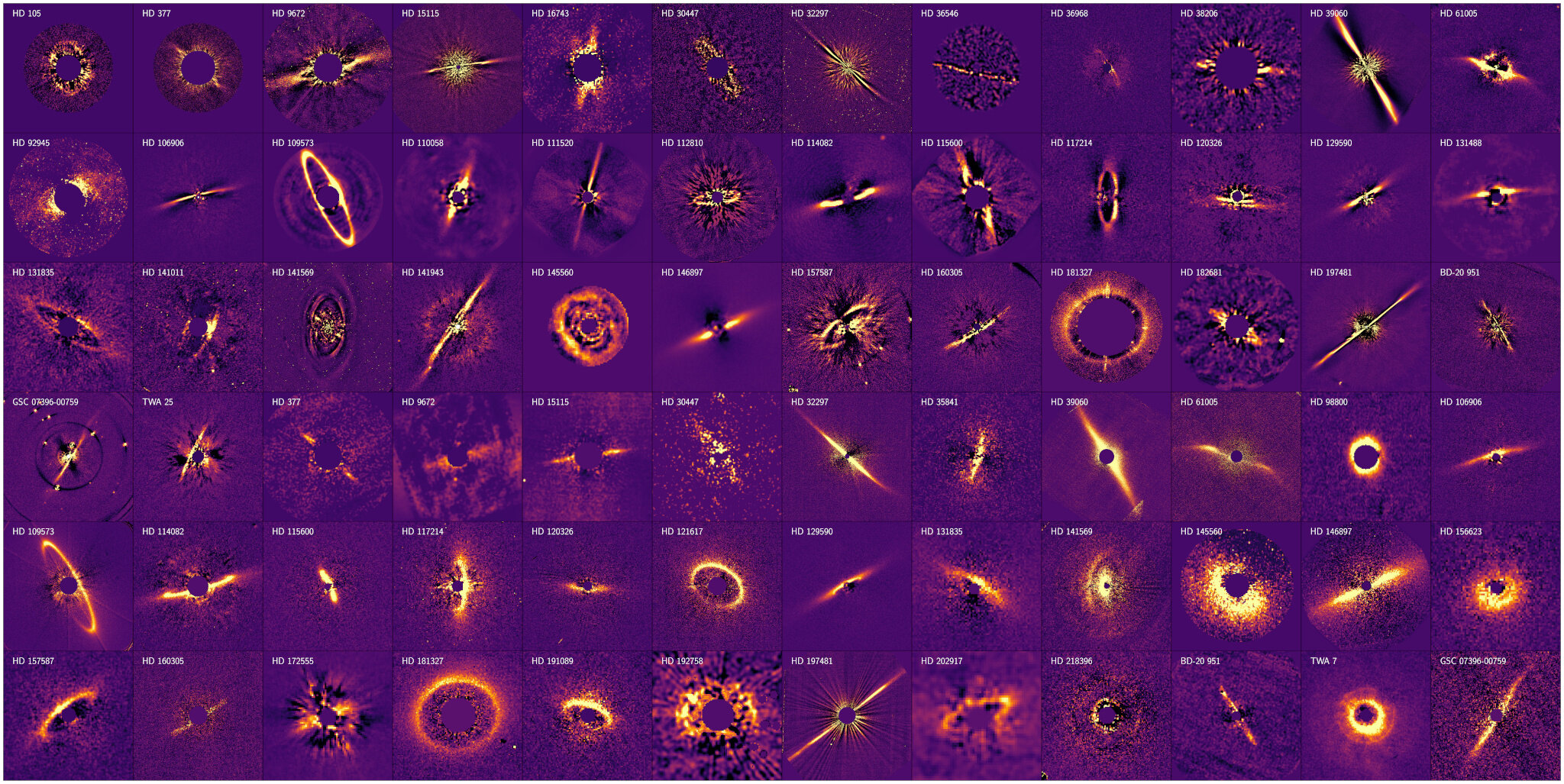

In a groundbreaking achievement, astronomers using the SPHERE instrument at ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) have captured an extraordinary gallery of images of “debris disks” around distant stars. These stunning observations provide rare glimpses into the building blocks of exoplanetary systems and give us a unique opportunity to peer into the early stages of planetary formation, far beyond our solar system.

As humans, we’ve always been fascinated by the night sky, wondering about the celestial bodies that fill it. And while we’ve been able to observe thousands of exoplanets—planets orbiting stars other than our own Sun—the small, elusive objects that might one day form planets have remained hidden. That is, until now. The SPHERE instrument, mounted on one of the world’s most advanced telescopes, has revealed an unprecedented collection of debris disks around young stars, providing insights into the material that surrounds planets before they fully take shape.

An Astronomical Treasure

Gaël Chauvin, project scientist for SPHERE and a co-author of the research, refers to this new data as an “astronomical treasure.” It’s a phrase that captures just how valuable these images are. For the first time, astronomers are able to observe the remnants of planetesimals—small bodies like asteroids and comets—in far-off planetary systems. These tiny objects, which are scattered across young star systems, are like fossils of the solar system’s earliest history. They offer a direct link to the time when our own planets were forming.

Chauvin’s excitement is shared by others in the field, including Dr. Julien Milli, an astronomer at the University of Grenoble Alpes, who emphasizes the difficulty of studying small bodies in distant planetary systems. “Finding any direct clues about the small bodies in a distant planetary system from images seems downright impossible,” he explains. And yet, SPHERE has managed to reveal these faint traces of dust and debris—evidence of the chaotic, early years of star systems.

Dust That Tells a Story

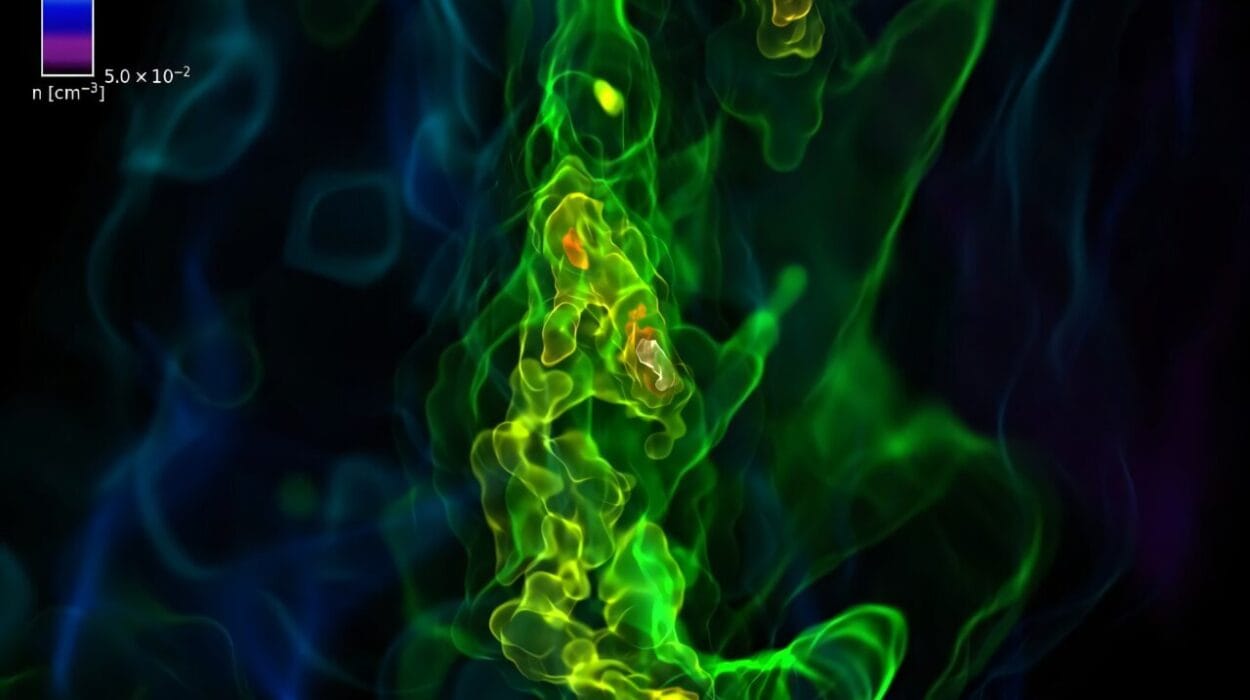

The key to unlocking this mystery lies in dust—the very stuff that makes up debris disks. When planetesimals like asteroids or comets collide, they produce copious amounts of dust, and this dust is visible across vast distances. While the planets themselves may be difficult to see, the dust they create tells a different story.

Picture an asteroid the size of a mountain, breaking apart into countless smaller particles. As each particle is split apart, it exposes far more surface area to the surrounding light, allowing it to reflect starlight in a way that can be detected by powerful telescopes. This reflection of light allows astronomers to study these distant debris disks in stunning detail, revealing the nature of the material surrounding young stars.

In our own solar system, we have remnants of these small bodies, such as the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and the Kuiper belt beyond the orbits of the giant planets. These collections of rocky and icy bodies are relics of our solar system’s early days. However, these features are difficult to observe in distant systems—until now.

The Technical Marvel of SPHERE

Capturing clear images of debris disks is no easy feat. Astronomers face significant challenges when observing distant objects like these, often competing with the bright light from the central star of the system. Imagine trying to photograph a faint puff of smoke near a glaring stadium floodlight from several kilometers away. That’s the astronomical equivalent of what SPHERE has accomplished.

At the heart of SPHERE is a clever technique known as a coronagraph, a device that blocks out the overwhelming light from a star, allowing astronomers to focus on the faint glow of surrounding debris. However, this technique requires extreme precision, and to meet this challenge, SPHERE employs adaptive optics—a system that compensates for the distortions caused by the Earth’s atmosphere in real-time, ensuring the clearest possible images.

In addition to this, SPHERE’s advanced instruments can filter out light reflected by dust particles, making it easier to distinguish debris disks from starlight. This combination of technology allows the telescope to produce some of the most detailed images ever taken of distant star systems.

A First Look at Alien Asteroid Belts

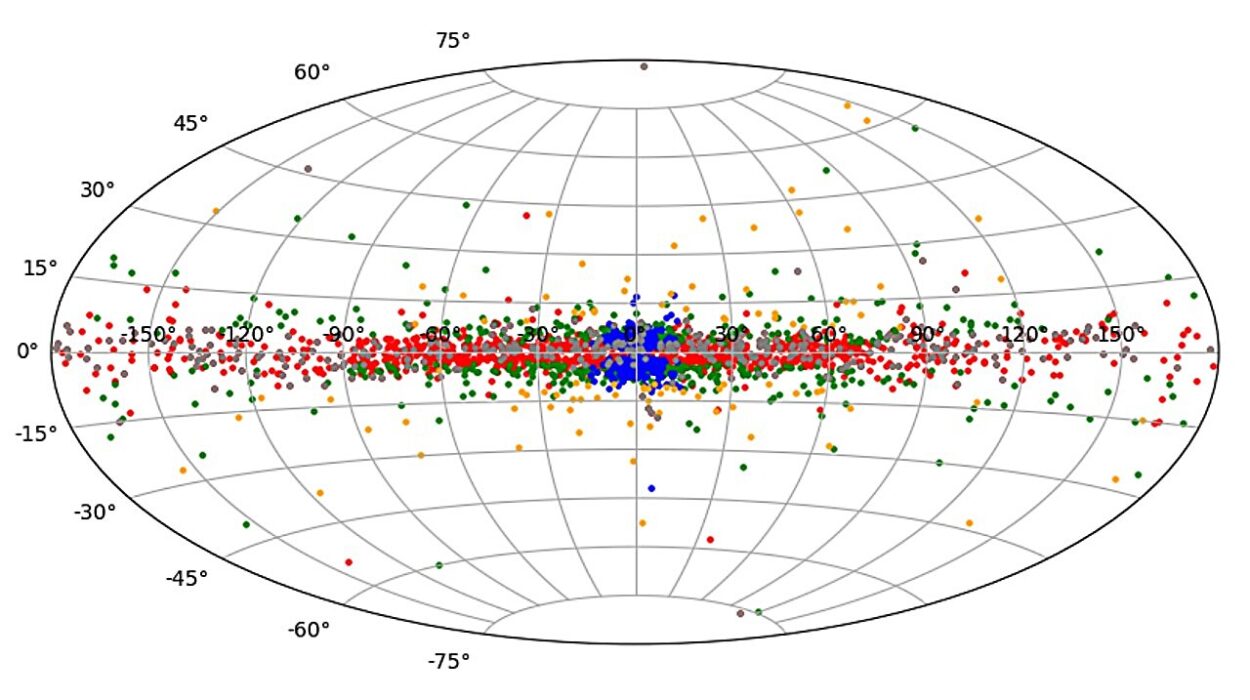

The new study, published in Astronomy and Astrophysics, presents a collection of debris disk images from 161 young stars. These stars, located relatively close to Earth, emit infrared radiation that indicates the presence of debris disks—a sure sign that planets may be forming. The resulting images reveal a staggering 51 debris disks, with a diverse range of shapes and sizes. Some disks are small and compact, while others are larger and more extended. Some are seen edge-on, while others appear nearly face-on, providing astronomers with various perspectives of these distant systems.

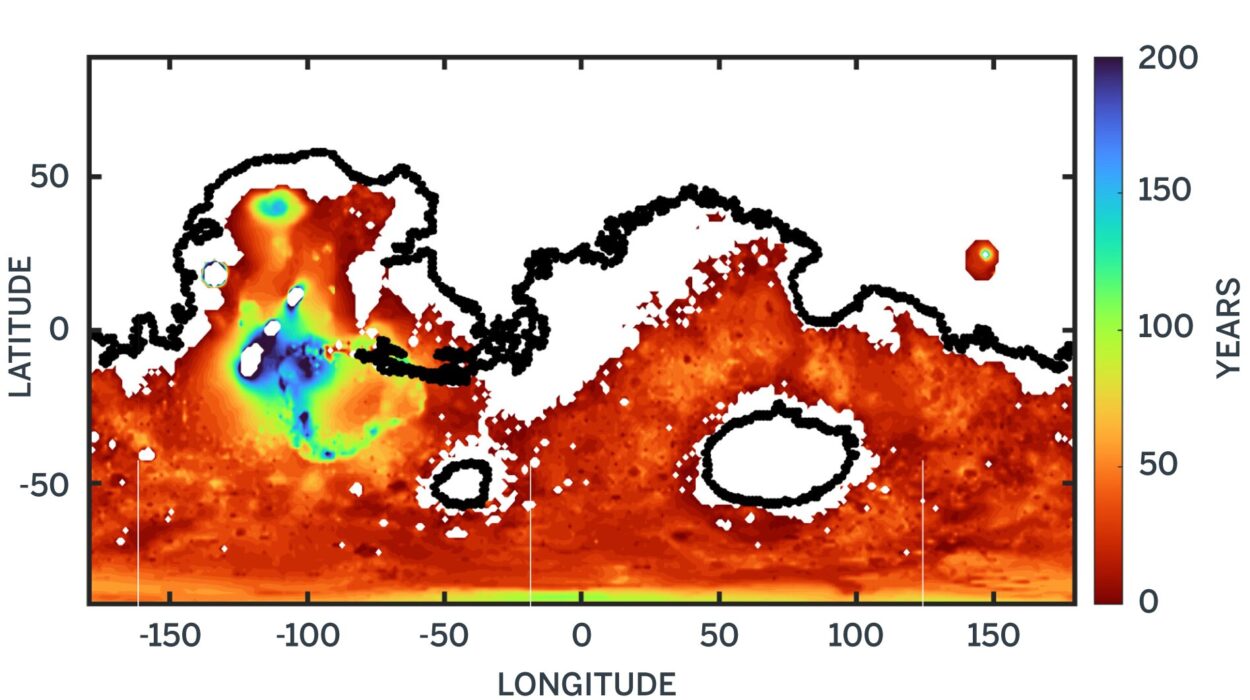

The discovery is significant for several reasons, not least because four of the debris disks were imaged for the first time. These new images offer tantalizing clues about the structure and evolution of these distant systems. For instance, many of the debris disks exhibit a ring-like structure, where material is concentrated at specific distances from the central star. This pattern mirrors the arrangement of small bodies in our own solar system, with the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and the icy Kuiper belt beyond Neptune.

What’s even more exciting is that some of these features hint at the presence of unseen planets. The sharp inner edges or asymmetries seen in certain debris disks could be the result of giant planets clearing their orbits of smaller bodies. These unseen planets are influencing the structure of the disk in ways that could eventually make them visible to the next generation of telescopes, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) or the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT).

What This Means for the Future of Astronomy

The images captured by SPHERE are not just beautiful; they hold the key to understanding the processes that govern the formation of planetary systems. By studying the debris disks in these far-off systems, astronomers are piecing together the puzzle of how planets form from the dust and gas that surround young stars. These disks, filled with debris from planetesimal collisions, are the birthplace of the building blocks that make up planets, moons, and other celestial bodies.

The findings also open up exciting possibilities for the future. As astronomers gain a deeper understanding of these disks, they can use the data to guide further observations with more advanced telescopes. The JWST, which is expected to launch soon, could take these observations to the next level, providing even clearer images of planets and their disks. In the coming years, the ELT—currently under construction by ESO—will allow astronomers to observe even fainter objects in the universe, bringing us closer to discovering planets and planetary systems that we once thought were beyond our reach.

Why This Research Matters

The research conducted with SPHERE is important for several reasons. First, it gives us a closer look at the processes that govern planet formation—an understanding that could help us answer one of humanity’s biggest questions: How did our own solar system come to be? But perhaps even more intriguing, it brings us closer to answering the question of whether we are truly alone in the universe. By studying debris disks around other stars, astronomers can gain insights into the likelihood of planets like Earth forming elsewhere, and whether those planets might host life.

As the study of exoplanets and planetary systems advances, the discoveries made by SPHERE will continue to shape our understanding of the universe. The data collected is a powerful reminder that the universe is full of wonders waiting to be uncovered—and that, just like our own solar system, countless others are in the process of being born.

More information: Characterization of debris disks observed with SPHERE, Astronomy and Astrophysics (2025). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202554953