Climate change is often spoken of as a crisis of the future, a looming storm that humanity must brace itself against. Yet archaeology reminds us that climate has always shaped human destiny. From the shifting sands of deserts to the submerged ruins along forgotten coastlines, the past whispers stories of resilience, adaptation, and collapse. Archaeology and climate change meet where earth and memory intersect—where ancient societies faced environmental upheaval, sometimes triumphing through ingenuity, sometimes faltering under its weight.

To study the link between archaeology and climate change is to hold a mirror to ourselves. It is to ask: How did people of the past respond to climate’s fluctuations? What can their experiences teach us about our own warming world? The answers, buried beneath soil and ice, are both humbling and hopeful.

Climate as a Force in Human History

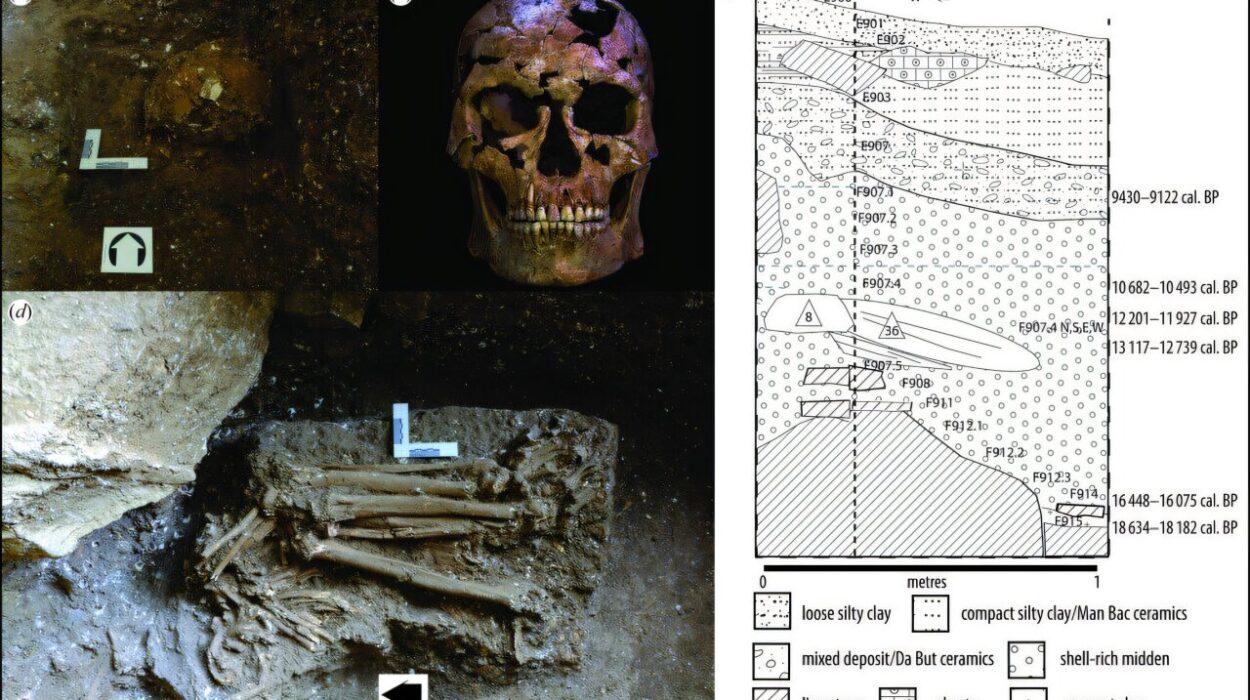

Climate is not just background scenery to history—it is one of its most powerful actors. Civilizations have risen during periods of stability, when predictable rainfall nourished crops, and have faltered when droughts or floods turned abundance into scarcity. Archaeology provides the evidence: pollen grains preserved in sediments, isotopes locked in bones, growth rings in ancient trees, and the ruins of settlements abandoned or fortified in response to shifting conditions.

Consider the African savannas, where the ebb and flow of rainfall influenced human migration and the spread of early Homo sapiens. Or the Fertile Crescent, where the balance of rivers and climate nurtured agriculture. Archaeology shows that climate has not only tested societies but has also sparked innovation—irrigation, storage, trade, and social organization often emerged as solutions to environmental uncertainty.

Lessons from the Ice

The Ice Age, or Pleistocene epoch, offers one of the clearest examples of climate’s hand in human history. As glaciers advanced and retreated, human groups adapted their tools, diets, and migration patterns. Archaeological sites across Europe reveal how Neanderthals and early modern humans responded to frigid landscapes with fire, clothing, and social cooperation.

When the last Ice Age ended about 11,700 years ago, melting glaciers transformed coastlines and created new ecosystems. The Holocene epoch, with its relatively stable climate, allowed agriculture to flourish. Archaeology captures this moment of transformation: the domestication of plants and animals, the rise of permanent settlements, and the birth of civilizations. Without this climatic stability, the trajectory of human history would have been profoundly different.

The Collapse of Civilizations

One of archaeology’s most compelling contributions to climate studies is the record of societal collapse. Civilizations that once seemed unshakable were, in fact, vulnerable to climate stress.

Take the Maya civilization in Mesoamerica. For centuries, the Maya built magnificent cities, developed advanced mathematics and astronomy, and cultivated vast agricultural systems. Yet evidence from lake sediments and cave stalagmites points to prolonged droughts between the 8th and 10th centuries CE. Archaeological findings—abandoned cities, signs of conflict, and declining construction—suggest that water scarcity undermined political stability, contributing to the Maya collapse.

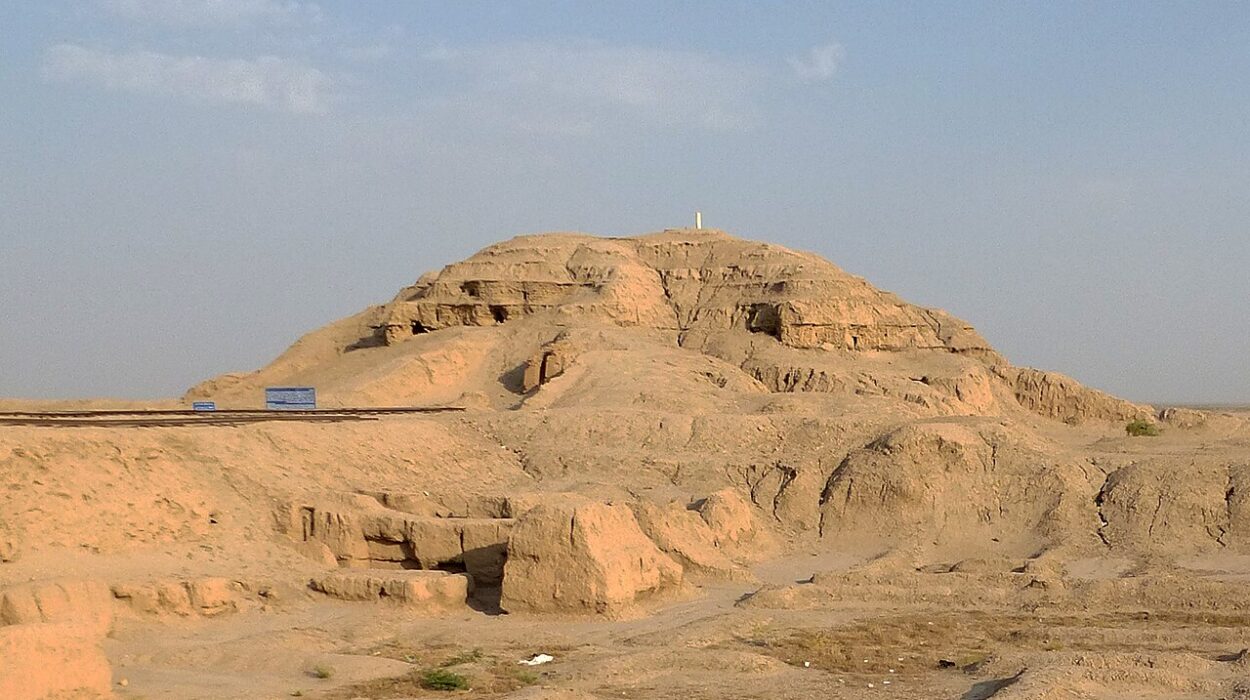

Or consider the Akkadian Empire of Mesopotamia, one of the world’s first empires. Archaeological and paleoclimate data reveal a severe drought around 2200 BCE, coinciding with the empire’s sudden decline. Crops failed, trade routes weakened, and the empire fragmented. Climate did not act alone—social, political, and economic tensions also played roles—but it was a decisive factor.

These stories are cautionary tales. They remind us that climate stress can destabilize even the most sophisticated societies, especially when combined with inequality, poor governance, or resource overexploitation.

The North Atlantic Oscillations and Viking Expansion

Archaeology also highlights how favorable climate can fuel expansion. During the Medieval Warm Period (roughly 950–1250 CE), relatively mild conditions in the North Atlantic allowed Norse seafarers to establish settlements in Greenland and even reach North America. Excavations in Greenland reveal farms, churches, and artifacts that testify to a thriving Norse presence.

Yet when the climate cooled during the Little Ice Age (around 1300–1850 CE), harsher winters and shorter growing seasons made survival in Greenland increasingly difficult. Archaeological evidence—such as dietary shifts from livestock to marine foods, signs of malnutrition, and eventual abandonment of settlements—reflects the Norse struggle against a changing environment.

The story of the Vikings underscores how climate offers both opportunity and challenge. Prosperity in warm times does not guarantee resilience when conditions shift.

Indigenous Knowledge and Adaptation

Not all stories are of collapse. Archaeology also reveals human ingenuity and resilience. Indigenous peoples across the world developed strategies to cope with climate variability long before modern science.

In the American Southwest, the Ancestral Puebloans built elaborate water management systems—reservoirs, dams, and canals—to survive in arid landscapes. Archaeological remains of terraced fields and cliff dwellings show how they maximized resources and created sustainable communities.

In the Andes, the Inca and their predecessors constructed terraced agriculture that reduced erosion, conserved water, and created microclimates. Archaeological studies of these terraces show that many are still functional today, offering lessons in sustainable farming under unpredictable conditions.

These examples remind us that adaptation is possible, that humans are not passive victims of climate but active problem-solvers. The challenge is to balance knowledge, cooperation, and innovation.

Climate Change Recorded in Archaeological Landscapes

Archaeology does not only study the human response to climate—it also preserves evidence of climate itself. Ancient shorelines, buried forests, and ice-preserved artifacts serve as natural archives.

Melting glaciers in the Alps have revealed tools, clothing, and even the frozen body of Ötzi the Iceman, who lived over 5,000 years ago. His discovery offers insights into Copper Age life but also demonstrates how climate change, by melting ice, releases long-hidden pasts.

Rising seas expose submerged settlements, from Doggerland in the North Sea—a land once connecting Britain to Europe—to ancient coastal villages drowned as ice melted after the Ice Age. Archaeology helps reconstruct these lost worlds, reminding us of the power of rising waters, a threat still present today.

Climate Archaeology as a Modern Science

Today, archaeologists and climate scientists work hand in hand. Archaeology provides deep time perspectives, showing how societies fared under different climatic regimes. Climate science, in turn, provides precise data from ice cores, sediments, and models. Together, they create a dialogue between past and present.

This interdisciplinary field, sometimes called “climate archaeology,” seeks to understand long-term human-environment interactions. By examining how past societies responded to droughts, floods, or warming, scientists hope to anticipate how modern societies might respond. Archaeology offers not only cautionary tales but also a repertoire of strategies that worked—and failed.

Modern Parallels and Warnings

The archaeological record resonates with today’s challenges. Just as the Maya struggled with drought, modern societies face water scarcity intensified by climate change. Just as the Norse settlements faltered under cooling, Arctic communities today confront melting permafrost and shifting ecosystems.

The past teaches that climate stress is rarely isolated—it interacts with political, economic, and social pressures. Societies that ignored inequality, overexploited resources, or failed to adapt suffered most. Those that invested in resilience, cooperation, and sustainable practices fared better. These lessons are urgently relevant as the world confronts rising seas, intensifying storms, and global warming.

Climate Change and the Fragility of Heritage

Climate change is not only a challenge to the present but also a threat to the past. Rising seas, desertification, melting permafrost, and wildfires endanger archaeological sites worldwide. Coastal erosion gnaws away at ancient settlements, while thawing tundra releases once-frozen remains.

Preserving this heritage is vital, not only for cultural memory but also for scientific knowledge. Archaeology helps us understand how humans have adapted before—and may adapt again. Losing these records would mean losing guides to our future.

The Human Story in the Face of Change

At its heart, the study of archaeology and climate change is the study of human vulnerability and resilience. It shows us that climate has always been a force shaping our destinies, but it also shows us that survival depends on choices.

Will we, like the Maya, overextend our resources and ignore warning signs? Or will we, like the Inca, develop strategies of adaptation that endure? The past does not dictate the future, but it provides a compass—a way to navigate uncertainty with the wisdom of history.

Conclusion: Listening to the Echoes

The ruins of ancient cities, the pollen grains in lakebeds, the bones of forgotten peoples—all speak to us across time. Archaeology does not reduce climate change to numbers on a graph; it restores the human face to environmental crises. It reminds us that climate change is not only about parts per million of carbon dioxide but also about hunger, migration, innovation, and survival.

What the past reveals is both sobering and empowering. Civilizations can and do fall when they ignore the climate. Yet humans have also shown resilience, creativity, and adaptability in the face of challenge.

As we stand at the edge of a rapidly warming world, archaeology invites us to listen to these echoes. To understand that our ancestors walked through climate crises of their own—and that their stories, carved into stone and soil, are not just relics of the past but warnings and guides for the future.