Archaeology has a way of whispering across centuries, turning fragments of bone and soil into stories of human struggle, survival, and identity. One such story emerges from the hills of northern Iran, where the remains of a Parthian man have shed light not only on the military culture of his people but also on the limits of ancient medicine. His grave, unearthed in the Liyar-Sang-Bon cemetery of Guilan Province, carries with it a narrative of violence, endurance, and technological mastery.

The Parthians, descendants of the Parnian tribe and part of the Dahae Union, were known as fearsome warriors. Masters of mounted archery, their military strategies baffled even the mighty Romans. Their skill in horsemanship and the precision of their weaponry left a mark on history, ensuring their place among the most formidable forces of the ancient world. Yet, beyond their battlefield renown, they were also artisans—gifted metalworkers whose weapons, horse gear, and accessories were admired even by their enemies.

It is within this world of warcraft and craftsmanship that the story of a single man’s injury and burial speaks volumes about the strength, resilience, and fragility of life in the Parthian era.

The Grave in Guilan

Between 2016 and 2018, three archaeological excavations at Liyar-Sang-Bon uncovered seventy-seven skeletal remains. Among them was a crypt grave holding an adult man. His body was laid to rest on his left side, legs bent in a flexed position, in accordance with burial traditions of his people. The skeleton, though poorly preserved, still offered valuable clues: portions of the pelvis, ribs, vertebrae, and left arm were missing, but the bones that remained carried the weight of history.

Beside him were grave goods—a handful of artifacts that paint a picture of the world he lived in. A jar stood out among them, crudely made with low firing quality, its construction lacking refinement. And yet, its polished exterior hinted at a final act of care, a vessel that held both symbolic and practical meaning. Inside were traces of smoke and the remains of a bird, perhaps an offering meant to accompany the deceased into the afterlife.

But it was not the pottery or the scattered objects that told the most compelling story. It was the bone itself—the right tibia of the man—that held a secret no less striking than the weapons that filled Parthian battlefields.

An Arrow in the Bone

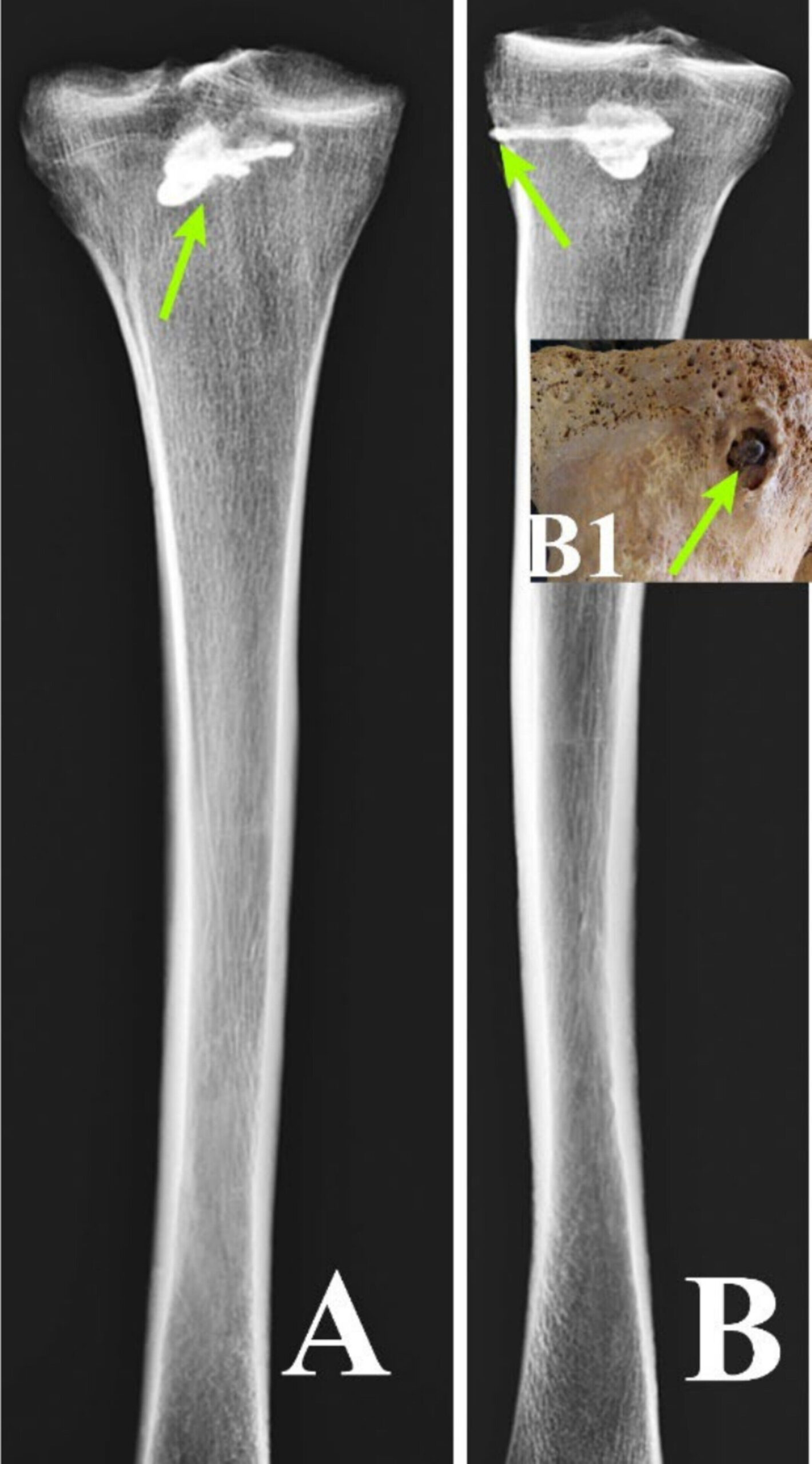

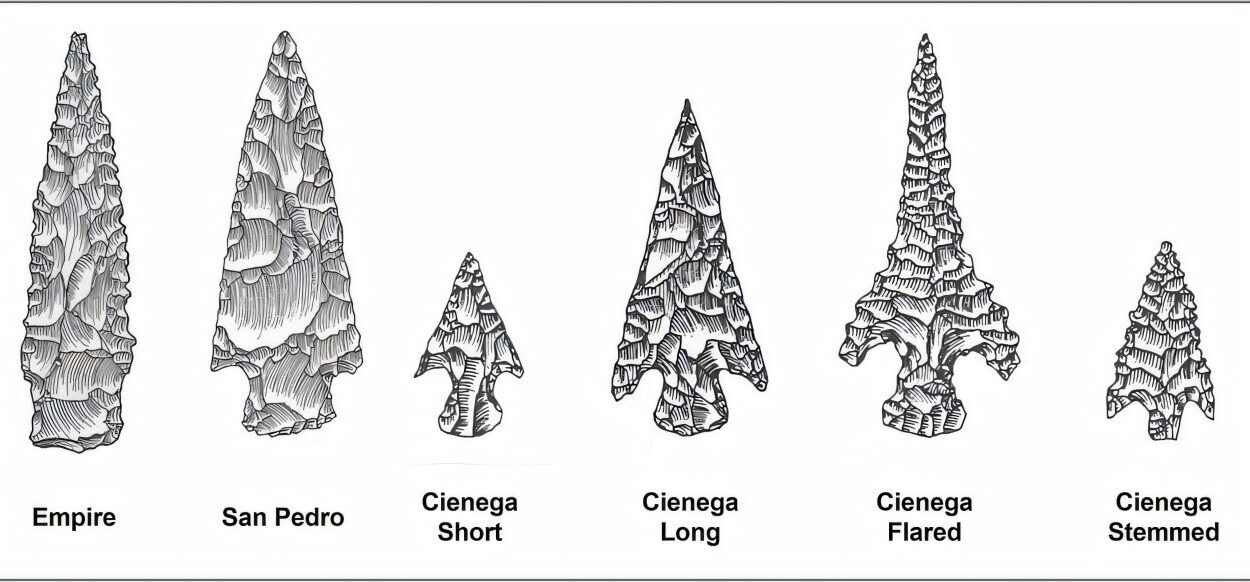

Using advanced tools such as X-ray fluorescence, quantometer analysis, and CT scans, researchers led by Dr. Mohammad Reza Eghdami identified a foreign object lodged deep within the man’s shinbone. It was a three-bladed iron arrowhead, 44 millimeters long and 15 millimeters wide, unmistakably Parthian in design.

The arrowhead was not just a remnant of war—it was a testament to the precision of Parthian craftsmanship. Its symmetry and lethal efficiency demonstrated the metallurgical expertise of a people whose skill in weapon-making was legendary. This was no accident of crude forging; it was a carefully designed tool of battle, meant to pierce flesh and bone, to disable and kill.

Yet the arrowhead told another story as well, one of survival. Examination revealed that dense bone tissue had begun to grow around the foreign object. The body of the warrior had attempted to heal, wrapping itself around the wound in a biological act of resilience. This growth indicated that the man did not die immediately after being struck. He lived for some time—perhaps weeks, months, or even longer—with a shard of iron lodged in his leg.

The Shadow of Pain and Survival

How long did he endure this injury? The answer may never be known. What is clear is that his body was locked in a battle of its own, trying to repair itself around the object that had caused such trauma. The absence of widespread infection or bone degradation suggested that his body adapted to the intrusion, though no evidence of surgical intervention was found.

This raises a poignant question: why was the arrowhead never removed? The Parthians were skilled in many domains, but surgery may not have been one of them. Dr. Eghdami notes that little is known about their medical practices. Unlike the Greeks or Egyptians, who left behind detailed records of their medical knowledge, the Parthians remain silent on this front. The embedded arrowhead thus serves as a sobering reminder of both their technological prowess and their medical limitations.

The wound also reveals the deeply human dimension of war. This man was not a nameless soldier lost in the chaos of battle; he was an individual who bore the weight of pain and survival. He lived long enough for his body to respond, for bone to grow around the metal shard, for the story of his endurance to be written into his skeleton.

The Warrior’s Legacy

Weapon-related injuries were rare among the remains at Liyar-Sang-Bon, making this find all the more remarkable. Only one other case in the cemetery—a knife wound to the throat and jaw—suggested violent death. The rest spoke of lives lived and ended in quieter ways. This scarcity underscores the significance of the man with the arrow in his leg: he was not just a statistic of war but a vivid reminder of its brutality and its survivors.

His injury also highlights the duality of Parthian culture. On one hand, their weapons were refined, deadly, and celebrated even by their enemies. On the other, their medical knowledge appears limited, their ability to treat such wounds constrained by the resources of their time. The arrow that gave them military superiority also exposed their vulnerability when it turned against their own.

Medicine in Silence

The Parthians left little direct evidence of their medical practices. Dr. Eghdami laments that scientific information about this aspect of their civilization remains scarce. Were they familiar with herbal remedies? Did they use poultices, cauterization, or bone-setting techniques? The record is largely blank.

Future research in paleobotany—the study of ancient plant remains—may reveal whether the Parthians used medicinal herbs to treat injuries like this one. Archaeologists also hope that medical texts or other indirect evidence might one day provide answers. For now, the silence persists, broken only by the testimony of bones.

A Story Larger Than One Man

The discovery of the arrowhead does more than tell us about one man’s fate. It enriches our understanding of the Parthian world—its warfare, its craftsmanship, its cultural values, and its limitations. It also bridges past and present, reminding us that the human experience of pain, resilience, and mortality has not changed.

When we imagine this man—perhaps a warrior, perhaps caught in the violence of conflict—we glimpse not only his suffering but his endurance. He lived long enough to heal, to leave behind evidence of survival against the odds. His story is not one of defeat but of persistence, written into his bones by the very arrow that was meant to end him.

Conclusion: The Arrow and the Echo

In the quiet earth of Guilan Province, one man’s wound has traveled across two thousand years to reach us. It speaks of the Parthians’ brilliance in warcraft, their artistry in metallurgy, and their silence in medicine. It tells of a life lived under the shadow of violence but marked by resilience.

Through this discovery, the past becomes immediate. We are reminded that behind every artifact lies a human life, with its struggles, hopes, and endurance. The arrow in the bone is not just a piece of metal—it is an echo of courage, a symbol of survival, and a testament to the enduring connection between the living and the dead.

The Parthian man’s story is not lost. It has been written into history by the hands of archaeologists and scientists, and into memory by those who listen. In this way, a single arrow preserves the humanity of a warrior, and through him, the spirit of an age.

More information: Mohammad Reza Eghdami et al, Weaponry and a Healed Wound From the Parthian Era (247 bce to 224 ce): Insights From the Liyarsangbon Cemetery, Guilan, Iran, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/oa.70038