In the rugged highlands of Jordan, archaeologists have uncovered a landscape unlike any other—one that whispers the story of how ancient people confronted the collapse of their world. The site, known as Murayghat, dates back nearly 5,000 years to the Early Bronze Age, and recent excavations led by researchers from the University of Copenhagen have revealed it as a remarkable center of ritual, remembrance, and rebirth.

Far from being a mere collection of stones, Murayghat represents an ancient response to crisis—a place where communities gathered to redefine themselves after the fall of an earlier civilization. It is a monument not only to death and ritual but also to human resilience, adaptation, and the enduring search for meaning in times of upheaval.

The World Before Murayghat

To understand Murayghat, one must first look at what came before. Around 4500–3500 BCE, the region was home to the Chalcolithic culture, a flourishing society known for its copper tools, rich symbolic art, and domestic settlements dotted with small shrines. This was a period of innovation and spiritual expression, when people lived in permanent villages and cultivated intricate community ties.

But that world did not last. Climate change, shifting trade routes, and internal social tensions seem to have led to the collapse of Chalcolithic society. Villages were abandoned. Copper production waned. The familiar rhythms of daily life gave way to uncertainty. And yet, rather than vanish, people adapted. They reimagined their relationship with the land, the dead, and the divine.

Out of this transformation arose the Early Bronze Age—and with it, the mysterious ritual landscape of Murayghat.

Stones of Memory and Meaning

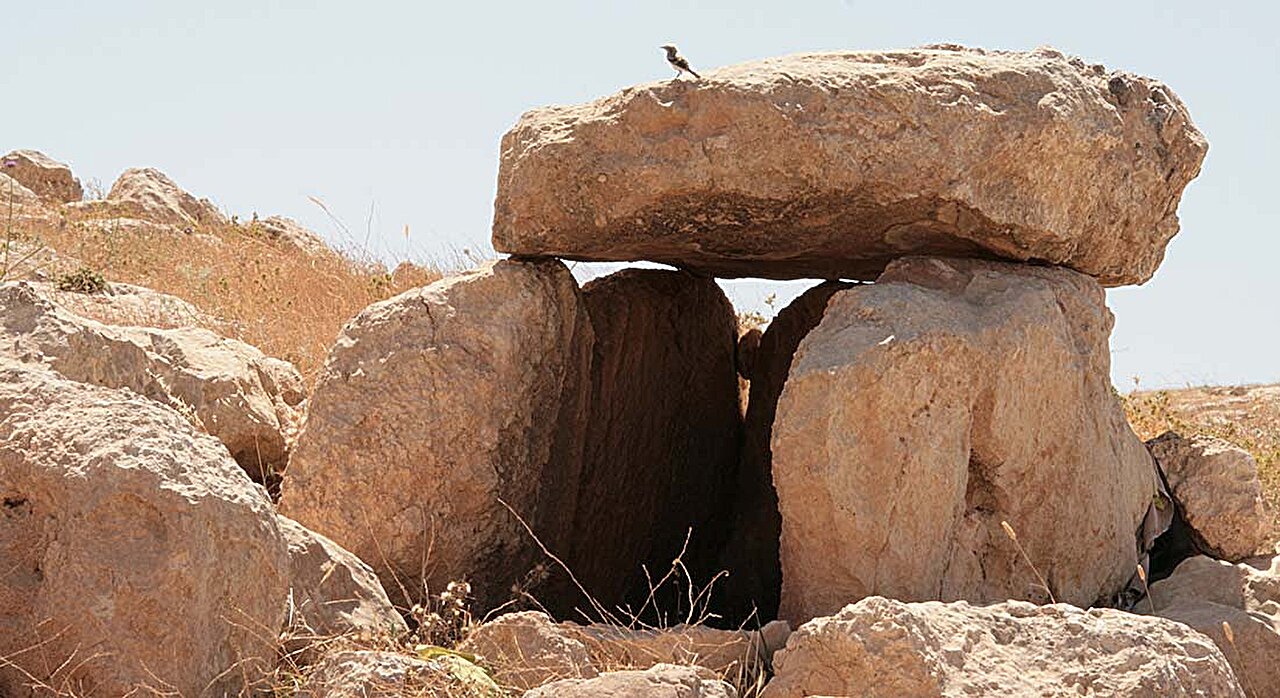

Led by archaeologist Susanne Kerner from the University of Copenhagen, the research team has uncovered a vast cluster of dolmens—stone burial monuments that stand like silent sentinels across the Jordanian hills. More than 95 dolmens have been documented so far, along with standing stones and megalithic enclosures that dominate the hilltop of Murayghat.

Unlike the domestic settlements of the Chalcolithic era, Murayghat was not a place for the living to dwell. There are no houses, no evidence of permanent habitation. Instead, the site appears to have been a space for ritual gatherings and communal burials, where early Bronze Age groups came together to honor their dead and renew their collective identity.

“The arrangement of dolmens and standing stones suggests deliberate design,” explains Kerner. “These were not random structures but visible symbols of belonging—markers of identity and territory in a time when traditional social systems had broken down.”

A New Kind of Community

What makes Murayghat extraordinary is not only its architecture but its social message. In the wake of societal collapse, when strong central authorities had faded, people used ritual and monument-building as tools for survival.

The dolmens, towering megaliths, and carved rock features may have served as communal anchors—physical expressions of a shared past and a redefined sense of belonging. By building these monuments, communities created new social roles and reasserted control over their landscape.

Murayghat’s hilltop location would have made it visible from miles around, a constant reminder of unity and identity. The monuments stood not only for the dead but also for the living, who found in ritual a way to rebuild social order when the old ways had crumbled.

The Archaeological Treasures of Murayghat

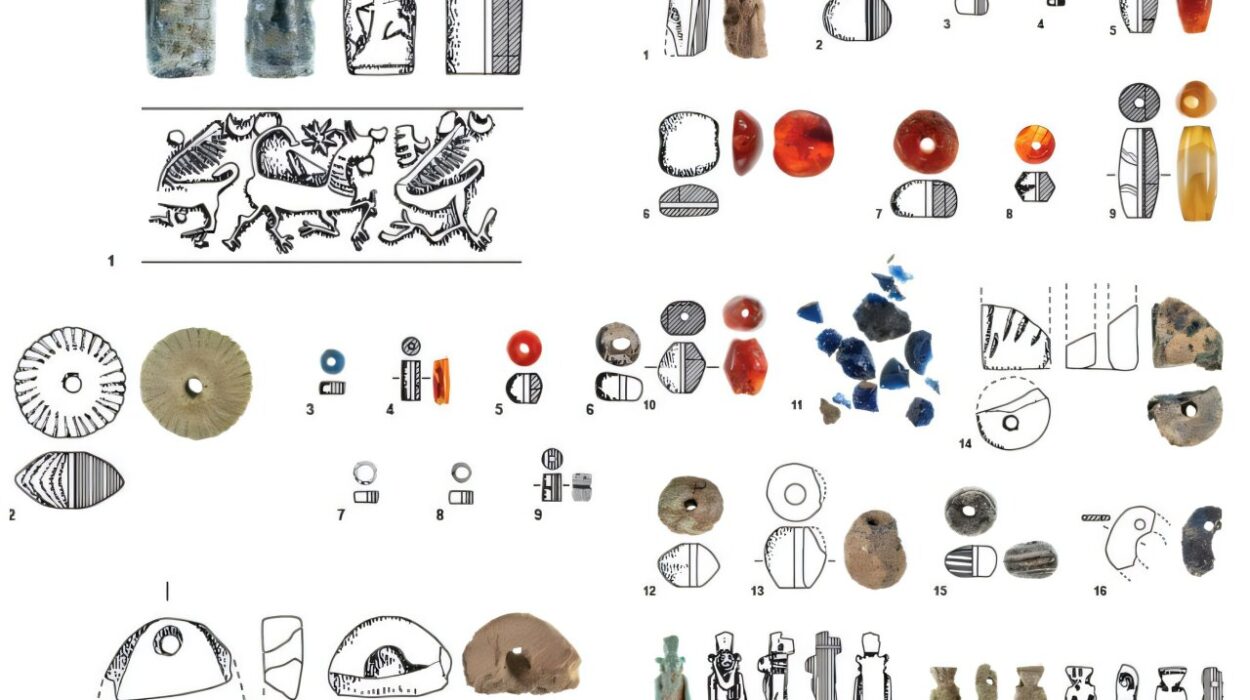

Beyond the monumental architecture, the excavations have revealed an abundance of artifacts that bring this ancient world vividly to life. Archaeologists have unearthed Early Bronze Age pottery, large communal bowls, grinding stones, flint tools, animal horn cores, and even copper objects—all traces of ritual activity and shared feasting.

These findings suggest that Murayghat was a gathering place, a ritual center where people from different groups met to commemorate, celebrate, and perhaps negotiate their relationships. The act of sharing food in communal bowls hints at ceremonies of renewal, feasting not just for sustenance but for spiritual and social cohesion.

The presence of copper artifacts—though rare—adds another layer of meaning. Copper had long been associated with craftsmanship and status in the Chalcolithic world, and its continued use at Murayghat may symbolize a conscious link to the past, a way of honoring old traditions while creating new ones.

Redefining Territory and Belonging

Kerner and her team believe that Murayghat played a vital role in redefining territory at a time when political and social structures were in flux. The visible placement of dolmens and standing stones across the hillsides may have served as markers of community space, delineating sacred or shared lands.

In a world without central rulers or formal boundaries, these monuments would have been powerful symbols—statements carved in stone about who people were and where they belonged.

“Murayghat gives us fascinating new insights into how early societies coped with disruption,” says Kerner. “When traditional authority faded, people turned to ritual and memory. They built monuments that redefined who they were and where they stood in the world.”

Rituals of Renewal in a Changing World

Archaeology often deals with fragments—broken pottery, weathered stones, scattered bones—but from these fragments, a profound human story can emerge. Murayghat tells one such story: that of a society rebuilding itself through ritual creativity.

In the Early Bronze Age, communities across the Levant faced environmental stress, resource scarcity, and social fragmentation. Yet instead of descending into chaos, many responded by creating new systems of meaning. Murayghat stands as a ritual landscape born from resilience, a spiritual map drawn by people determined to find balance between past and present, life and death, stability and change.

The site’s communal nature—its shared feasts, collective burials, and monumental expressions—suggests a deliberate move away from individual authority toward collective identity. In that sense, Murayghat was not just a cemetery or a shrine; it was a symbol of social renewal.

The Science and Spirit of Archaeology

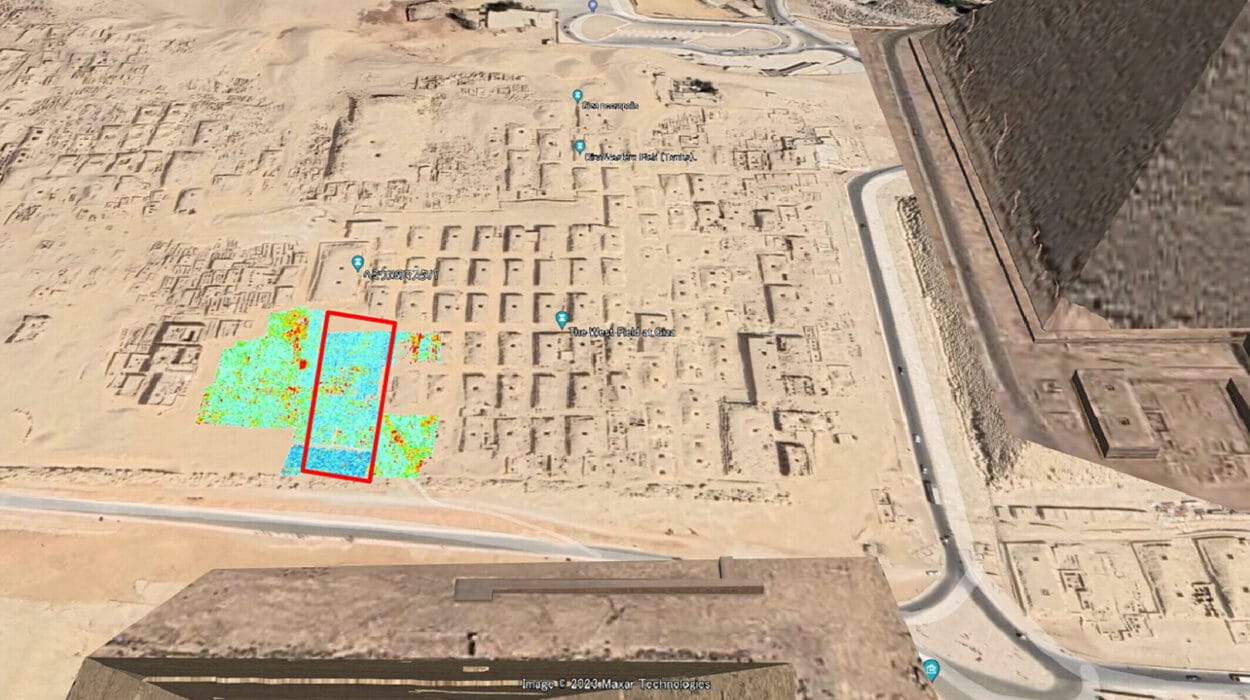

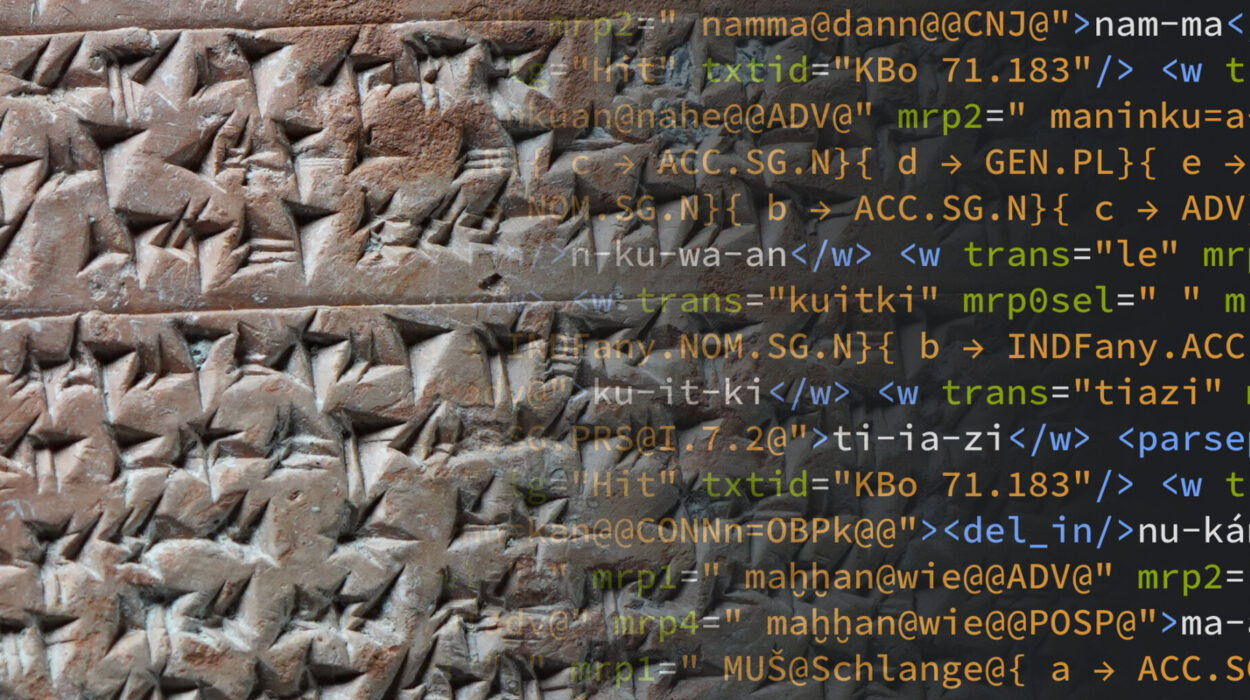

Kerner’s team combines traditional excavation with cutting-edge techniques, including drone mapping and 3D modeling, to reconstruct the ancient landscape. Their findings, recently published in the journal Levant under the title “Dolmens, Standing Stones and Ritual in Murayghat,” are helping to reshape our understanding of the Early Bronze Age in the Near East.

But beyond data and artifacts, the excavation at Murayghat also speaks to something deeply human—the enduring need to find meaning in the face of uncertainty. These ancient builders, with their monumental stones and sacred gatherings, were not so different from us. When their world changed, they responded with creativity, cooperation, and reverence for what connected them.

Echoes Through Time

Standing among the dolmens of Murayghat today, one can almost feel the echoes of those long-ago gatherings—the hum of voices, the glow of firelight against stone, the rhythmic pounding of grain into flour for a communal feast.

The landscape, though silent now, once pulsed with ritual energy. It was a place where memory was not written in books but carved into bedrock. Each monument was a promise: that life would continue, that communities would endure, that meaning could be rebuilt from ruin.

A Legacy of Adaptation

Murayghat is more than an archaeological site—it is a testament to human adaptability. It reveals that even 5,000 years ago, people possessed the same emotional and social intelligence that guides us today. They faced climate change, resource scarcity, and social upheaval, yet found ways to reinvent their world through collaboration and ceremony.

In studying Murayghat, we learn not only about ancient Jordan but about ourselves. We see that the impulse to create, to remember, and to come together in times of crisis is deeply woven into what it means to be human.

The Story That Still Unfolds

As research continues, Murayghat promises to reveal even more about the people who built it—their rituals, their beliefs, and their strategies for survival. Each excavation uncovers new clues, each stone adds another verse to the story of how humanity endures.

Murayghat reminds us that even in the face of collapse, there is always the possibility of renewal. When old worlds fall apart, new meanings arise from the dust. And across the millennia, the stones still speak, telling us that the power to rebuild—through ritual, memory, and shared identity—has always been at the heart of the human story.

More information: Susanne Kerner, Dolmens, standing stones and ritual in Murayghat, Levant (2025). DOI: 10.1080/00758914.2025.2513829