For decades, oncologists have known that cancer doesn’t play fair between the sexes. Men are statistically more likely to develop most cancers, but women—especially before menopause—carry their own invisible vulnerabilities. Melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, is one of them. Despite rigorous sun protection campaigns, younger women remain inexplicably susceptible to the disease’s more aggressive forms. Now, thanks to a groundbreaking study from researchers at Institut Curie, we may finally know why.

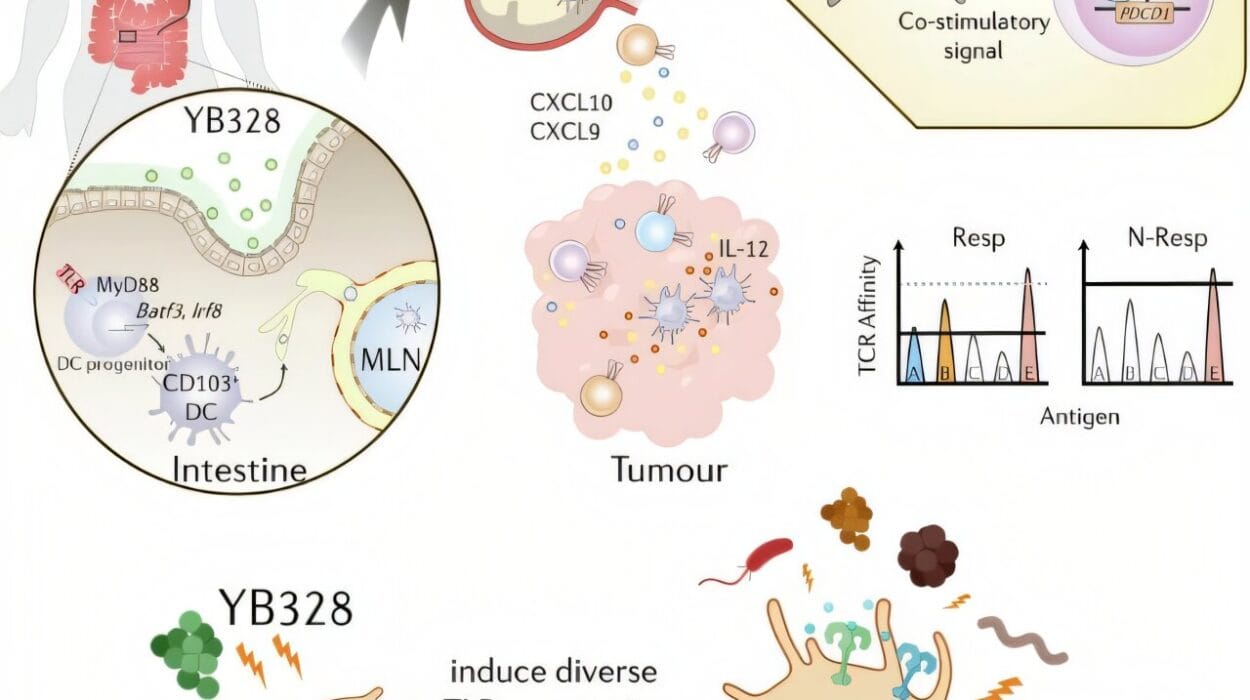

Published in the prestigious journal Nature, the study reveals a sex-specific molecular chain reaction that only activates under particular conditions—chief among them, the loss of a key adhesion protein called E-cadherin. This cascade involves the estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and a lesser-known but potent player: the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR).

The discovery doesn’t just solve a mystery; it could rewrite how doctors treat melanoma—and potentially many other cancers—in women.

The Guardian Protein That Silently Vanishes

To understand the implications, we need to meet E-cadherin. This molecule acts like biological glue, anchoring cells together and preventing them from slipping into the bloodstream and colonizing distant organs—a process we know as metastasis.

But E-cadherin often vanishes early in cancer development, particularly in aggressive tumors. Its absence has been noted before, but this new research digs deeper into what happens after it disappears, especially in female patients.

Using an advanced mouse model of melanoma, the Institut Curie team induced tumors in animals both with and without the E-cadherin gene. What they found was startling: although tumor size and timing were similar in all mice, female mice without E-cadherin developed lung metastases nearly four times more often than those with the protein intact.

It was a signal that something deeper was at play—something that had, until now, gone unnoticed.

A Receptor Emerges from the Shadows

When researchers zoomed in on the tumors, they discovered the culprit: GRPR, a receptor typically buried in the background of cancer biology. GRPR is a G-protein-coupled receptor, the kind often involved in transmitting signals inside cells. It’s not usually associated with melanoma—until now.

In E-cadherin-deficient female melanoma cells, GRPR was expressed at dramatically higher levels than in male cells or those with normal E-cadherin. Intriguingly, when scientists artificially introduced GRPR into melanoma cells, even without any other changes, those cells became significantly more metastatic in mice.

But the truly remarkable result came when they blocked GRPR with a drug called RC-3095. Suddenly, the runaway metastasis stopped in its tracks.

“This was a lightbulb moment,” said lead investigator Dr. Masaaki Miyahara. “We had a pathway we could see, manipulate, and—most importantly—shut down.”

A Loop That Feeds on Itself

The study didn’t stop at the surface. The team wanted to understand how E-cadherin loss could trigger such a dramatic GRPR surge. The answer lay in a well-known molecular troublemaker: β-catenin.

In healthy cells, β-catenin is held in check by E-cadherin. But when E-cadherin vanishes, β-catenin runs free, activating genes it shouldn’t. One of those is ESR1, the gene that encodes estrogen receptor-α (ERα)—a hormone receptor central to breast cancer biology. Once activated, ERα ramps up production of GRPR.

Even more troubling, GRPR itself seems to suppress E-cadherin further, creating a self-sustaining loop: loss of E-cadherin leads to more GRPR, which in turn prevents E-cadherin from coming back, pushing the tumor deeper into its metastatic identity.

“This feedback loop acts like a runaway train,” said Dr. Miyahara. “And in female cancers, especially those with hormone sensitivity, it may explain why certain tumors escalate so rapidly.”

Borrowing Tools from Breast Cancer

Here’s where the story takes a hopeful turn. Because ERα is already a familiar target in breast cancer, there are already clinically approved drugs designed to block it—most notably, Fulvestrant. The Institut Curie team tested Fulvestrant on their melanoma models and found that it significantly reduced metastasis, especially in female subjects with high GRPR levels.

This suggests that tools designed for one cancer could be repurposed for another—provided we understand the underlying biology.

It also suggests that melanoma, long considered hormone-independent, might not be so independent after all, at least not in women.

A Future of Sex-Specific Cancer Medicine

The study adds to a growing body of research showing that men and women don’t just experience cancer differently—they may need to be treated differently too. For too long, female-specific mechanisms have gone underexplored, with most therapies designed for a hypothetical “average patient” who often skews male.

This research forces a rethinking of that paradigm.

“This isn’t just a melanoma story,” said Dr. Miyahara. “It’s a story about how we’ve overlooked sex-specific biology in cancer for too long. Our findings suggest that hormone signaling, especially in the context of cell adhesion loss, might play a much bigger role in many tumors than we ever realized.”

The implication? Hormone pathway inhibitors could become part of treatment regimens not just for breast or ovarian cancer, but for melanomas and perhaps other solid tumors where E-cadherin is lost.

The Questions Still Ahead

As with any scientific breakthrough, this discovery opens as many doors as it closes. How widespread is this ERα–GRPR axis in other cancers? Could it explain aggressive disease patterns in other premenopausal cancers? Might it help explain recurrence patterns or treatment resistance?

Future studies will focus on these questions, as researchers explore how this molecular circuit operates in other tumor types and patient populations.

Meanwhile, the GRPR inhibitor RC-3095 and ERα blockers like Fulvestrant could enter trials for new indications, guided by biomarkers such as E-cadherin loss or GRPR expression levels. The hope is that precision medicine will finally start accounting for precision biology—down to the chromosomal level.

Beyond the Genome: A Gendered Future for Cancer Care

In a time when cancer care is rapidly evolving toward personalization, this research stands as a reminder that genes aren’t the only factor worth customizing for. The human body is shaped not just by DNA, but by hormones, environments, and yes—sex.

For too long, the influence of hormones on cancers like melanoma has been treated as an afterthought. But in the loss of one molecule—E-cadherin—and the rise of another—GRPR—we’re beginning to see how female biology weaves itself into cancer’s script in unexpected, sometimes devastating, ways.

Thanks to the researchers at Institut Curie, that script is being rewritten—and with it, the future of cancer therapy for millions of women worldwide.

References: Jérémy H. Raymond et al, Targeting GRPR for sex hormone-dependent cancer after loss of E-cadherin, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09111-x

Svenja Meierjohann, Sex differences in skin-cancer risk are linked to oestrogen levels, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/d41586-025-01708-6