For most of human history, matter appeared simple. It came in three familiar forms: solids that held their shape, liquids that flowed but stayed together, and gases that dispersed into invisibility. These categories were enough to explain ice melting into water, water boiling into steam, and stone remaining stubbornly rigid beneath our feet. Yet as physics pushed deeper into extremes of temperature, pressure, and quantum scale, this tidy picture began to fracture. Matter revealed behaviors so unfamiliar that they defied everyday intuition, forcing scientists to expand the very definition of what a “state” of matter can be.

These strange states are not science fiction. They are real, experimentally verified forms of matter that arise under specific physical conditions, often far removed from normal human experience. Some exist near absolute zero, where quantum effects dominate. Others emerge in extreme electromagnetic fields or inside stars. Each one reveals something profound about how particles interact, how energy shapes structure, and how the universe organizes itself at its most fundamental level.

What follows are six of the most fascinating and scientifically established states of matter beyond solids, liquids, and gases. Each represents a triumph of human curiosity and a reminder that reality is far richer than it appears at first glance.

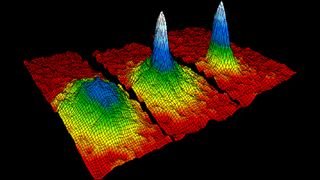

1. Bose–Einstein Condensate: Matter Acting as a Single Quantum Wave

The Bose–Einstein condensate is often described as the coldest form of matter in the universe. It arises when certain particles are cooled to temperatures just a tiny fraction above absolute zero, the point at which thermal motion nearly vanishes. At these extreme conditions, matter stops behaving like a collection of individual particles and instead acts as a single, coherent quantum entity.

The theoretical foundation of this state was laid in the early twentieth century by Albert Einstein and Satyendra Nath Bose. They predicted that particles known as bosons, when cooled sufficiently, would collapse into the same lowest-energy quantum state. For decades, this remained a mathematical curiosity. Only in the 1990s did experimental techniques become precise enough to create Bose–Einstein condensates in the laboratory.

In this state, atoms lose their individual identities. Their wavefunctions overlap so completely that the entire condensate can be described by one quantum wave. This leads to astonishing properties. The condensate can flow without viscosity, climb walls under certain conditions, and display interference patterns normally associated with light rather than matter.

Emotionally, the Bose–Einstein condensate is unsettling and beautiful. It challenges the deeply ingrained notion that matter is made of distinct, separate objects. Instead, it reveals that individuality itself can dissolve under the right conditions. Matter becomes collective, unified, and profoundly quantum. This state provides direct experimental access to quantum mechanics on a macroscopic scale, allowing scientists to observe quantum behavior not just in equations, but in visible, measurable matter.

Beyond its conceptual importance, the Bose–Einstein condensate has practical implications. It is used to study superconductivity, quantum magnetism, and precision measurement. Yet its greatest significance lies in what it teaches us about reality: that at the deepest level, the universe is governed not by solid certainty, but by waves of probability that can merge into a single, harmonious whole.

2. Plasma: The Electrified State That Dominates the Universe

Plasma is sometimes called the fourth state of matter, but its strangeness goes far beyond a simple extension of gas. When a gas is heated to extremely high temperatures or subjected to intense electromagnetic fields, its atoms lose electrons, becoming a mixture of positively charged ions and free electrons. This ionized state behaves in ways that are radically different from ordinary gases.

Unlike neutral gases, plasma responds strongly to electric and magnetic fields. It can form filaments, glow with eerie light, and generate complex, self-organizing structures. These behaviors arise because charged particles interact not only through collisions, but also through long-range electromagnetic forces.

Plasma is rare on Earth under natural conditions, yet it dominates the visible universe. Stars, including the Sun, are vast spheres of plasma. Lightning, auroras, and solar flares are plasma phenomena. Even the tenuous gas between galaxies exists primarily in a plasma state. In terms of sheer abundance, plasma is the most common form of matter in the cosmos.

What makes plasma emotionally compelling is its dual nature. It is both familiar and alien. We see it in neon signs and plasma globes, yet its behavior often appears alive, twisting and pulsing as if guided by intention. This apparent vitality emerges from the collective dynamics of charged particles, governed by well-understood physical laws but producing visually dramatic results.

Plasma physics is central to humanity’s future ambitions. Controlled nuclear fusion, a potential source of near-limitless clean energy, relies on confining plasma at extreme temperatures. Understanding plasma also protects modern technology, as solar plasma storms can disrupt satellites and power grids.

Plasma teaches us that matter is not passive. Under the right conditions, it becomes dynamic, interactive, and structurally complex. It blurs the boundary between matter and energy, reminding us that the universe is not built from static substances, but from restless, charged motion.

3. Superfluid: Matter That Flows Without Resistance

A superfluid is a state of matter that defies one of the most basic assumptions of everyday experience: that motion always involves friction. In a superfluid, liquid flows without viscosity, meaning it can move endlessly without losing energy. Once set in motion, it does not slow down.

This state emerges when certain liquids are cooled to temperatures near absolute zero. Liquid helium is the most famous example. When helium-4 is cooled below a critical temperature, it undergoes a phase transition into a superfluid state. At this point, its atoms condense into a collective quantum state, similar in spirit to a Bose–Einstein condensate, but occurring in a liquid.

Superfluids exhibit behaviors that appear almost magical. They can climb the walls of their containers, leak through microscopic pores that would block ordinary liquids, and form persistent vortices that rotate indefinitely. These effects arise because the fluid’s particles move in perfect coordination, constrained by quantum mechanics rather than classical physics.

The emotional impact of superfluidity lies in its challenge to intuition. Friction feels inevitable. It defines our physical world, from walking to breathing. Superfluids reveal that friction is not a fundamental property of matter, but a consequence of disorder and thermal motion. When that disorder is removed, matter flows with perfect efficiency.

Superfluidity is not merely a laboratory curiosity. It plays a role in astrophysics, particularly in the interiors of neutron stars, where superfluid neutrons are thought to influence the star’s rotation and thermal behavior. On Earth, superfluids provide insight into quantum coherence, phase transitions, and the boundary between classical and quantum worlds.

Through superfluids, physics shows that even the most familiar substances can hide extraordinary behaviors, waiting to emerge when conditions are pushed to their limits.

4. Superconductor: Matter That Carries Electricity Perfectly

Superconductivity is a state of matter in which electrical resistance drops to zero. In a superconducting material, electric current flows without energy loss, allowing charges to move indefinitely once set in motion. This phenomenon emerges when certain materials are cooled below a critical temperature.

At the microscopic level, superconductivity arises from a delicate quantum mechanism. Electrons, which normally repel each other due to their negative charge, become paired through interactions with the material’s atomic lattice. These pairs move in a coordinated, wave-like manner that avoids the scattering processes responsible for electrical resistance.

Superconductors display additional strange properties. They expel magnetic fields from their interior, a phenomenon known as the Meissner effect. This allows magnets to levitate above superconducting materials, creating a visually striking demonstration of quantum physics made tangible.

The emotional resonance of superconductivity comes from its promise. Energy loss is a fundamental limitation in modern technology. Power lines waste energy as heat, electronic devices require constant cooling, and efficiency always has a ceiling. Superconductors offer a glimpse of a world where these constraints are lifted, where electricity flows perfectly and silently.

Although practical superconductors currently require very low temperatures or specialized materials, ongoing research continues to push the boundaries toward higher-temperature superconductivity. The scientific challenge is immense, but the potential rewards are transformative.

Superconductivity shows that matter can organize itself into states of extraordinary order, where collective quantum behavior overrides individual randomness. It reveals that perfection, at least in a physical sense, is not only imaginable but experimentally real.

5. Degenerate Matter: The Crushing Physics of Extreme Density

Degenerate matter exists under conditions so extreme that they are almost impossible to replicate on Earth. It is found primarily in the remnants of dead stars, such as white dwarfs and neutron stars. In these environments, gravity compresses matter to densities millions or trillions of times greater than those of ordinary solids.

In degenerate matter, quantum mechanics takes control of structure. The pressure supporting the material against further collapse does not come from thermal motion, as in gases, but from the principles of quantum exclusion. Fermions, such as electrons or neutrons, cannot occupy the same quantum state. When packed tightly together, this restriction generates an immense pressure known as degeneracy pressure.

White dwarf stars are supported by electron degeneracy pressure, while neutron stars rely on neutron degeneracy pressure. In both cases, matter behaves unlike anything encountered in everyday life. Atoms are crushed, electrons are forced into extreme configurations, and matter becomes astonishingly rigid despite its immense density.

The emotional weight of degenerate matter lies in its cosmic significance. It represents the final stand of matter against gravity, the boundary between stability and collapse. When degeneracy pressure fails, matter gives way to black holes, where known physics breaks down entirely.

Degenerate matter reminds us that the states of matter are not merely laboratory curiosities. They shape the life cycles of stars, the distribution of elements, and the structure of the universe itself. Physics, in this context, becomes a story of survival under unimaginable pressure.

6. Quark–Gluon Plasma: Matter at the Dawn of the Universe

The quark–gluon plasma is one of the most extreme states of matter ever studied. It exists at temperatures and energies so high that protons and neutrons dissolve into their fundamental components: quarks and gluons. In this state, quarks move freely, no longer confined within individual particles.

This form of matter is believed to have filled the universe microseconds after the Big Bang, before cooling allowed quarks to bind together into the particles that make up atoms today. Creating quark–gluon plasma requires enormous energy, achieved only in powerful particle accelerators through high-energy nuclear collisions.

What emerges from these experiments is a state that behaves neither like a gas nor a liquid in the classical sense. Instead, quark–gluon plasma flows like an almost perfect fluid, with extremely low viscosity, despite existing at trillions of degrees.

The emotional power of this state lies in its connection to cosmic origins. Studying quark–gluon plasma is not merely about exotic physics; it is about reconstructing the earliest moments of existence. It allows scientists to probe conditions that shaped the entire structure of the universe.

Quark–gluon plasma demonstrates that matter, under sufficient energy, sheds its familiar forms and reveals deeper layers of organization. It shows that even the particles we consider fundamental can dissolve into something more primitive, more fluid, and more universal.

Conclusion: Matter Is Far Stranger Than It Appears

These six strange states of matter reveal a universe far richer than the simple categories learned in school. Solid, liquid, and gas describe only a narrow band of physical reality, shaped by the conditions of Earth’s surface. Beyond that narrow band lies a vast landscape of behaviors governed by quantum mechanics, relativity, and extreme conditions.

Each exotic state tells a story. Bose–Einstein condensates whisper of unity and coherence. Plasma crackles with energy and cosmic dominance. Superfluids and superconductors reveal perfection hidden beneath disorder. Degenerate matter stands as a monument to quantum resistance against gravity. Quark–gluon plasma carries echoes of the universe’s birth.

Together, they remind us that matter is not static or simple. It is dynamic, adaptable, and endlessly surprising. To study these states is not only to expand scientific knowledge, but to deepen our sense of wonder. Physics shows us that reality is stranger, more beautiful, and more emotionally resonant than common sense ever suggests.