In the heart of the Mediterranean, on the rugged island of Sardinia, a unique civilization flourished during the Bronze Age. Known today as the Nuraghe culture, these people left behind one of the most extraordinary archaeological legacies in Europe: their iconic stone towers called nuraghi and their enigmatic bronze figurines, the bronzetti.

The nuraghi—towering megalithic structures that still rise from the Sardinian landscape—are silent witnesses to a society that combined military strength, ritual practice, and far-reaching trade networks. But it is the bronzetti, small yet powerful bronze sculptures depicting warriors, animals, deities, and daily life, that have captivated scholars for generations. Their stylized forms—helmeted warriors, archers, and horned figures—speak to a culture of symbolism and artistry.

For years, one puzzle has remained: where did the copper used to make these bronzetti come from? The answer to that question is not just about metallurgy; it reveals the threads of connection between Sardinia, the wider Mediterranean, and even distant northern Europe.

Unlocking Metal’s Origins: A New Scientific Breakthrough

Until recently, determining the precise origins of ancient metals was notoriously difficult. Copper, tin, and lead—the essential components of bronze—often carry overlapping chemical signatures that blur their provenance. Traditional methods could only provide hints, not certainties.

That changed with the development of a multi-proxy approach at the Curt-Engelhorn Center for Archaeometry in Mannheim. By combining analyses of copper, tin, lead, and the rarer osmium isotopes, researchers gained a much clearer picture of where the bronzetti metals originated.

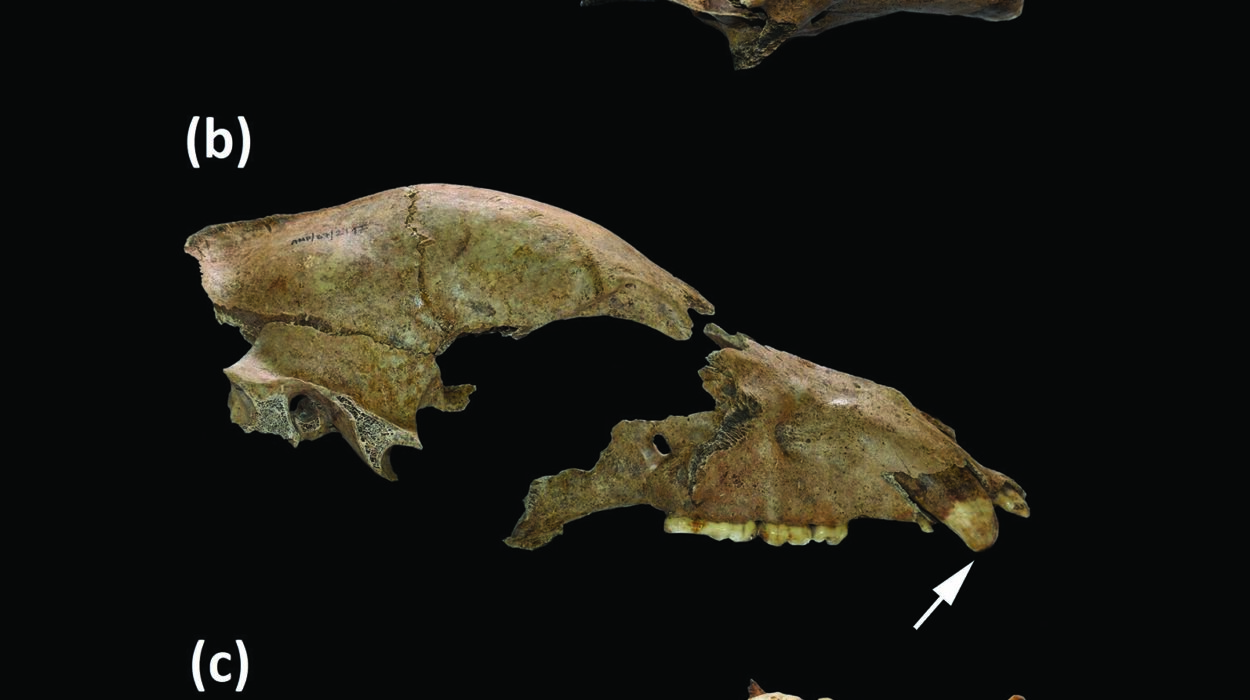

Dr. Daniel Berger, who spearheaded this work, emphasized how osmium isotopes provided the decisive breakthrough. The analysis revealed that the copper used in Sardinian bronzetti came primarily from Sardinia itself, though in some cases it was mixed with copper imported from the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal). Surprisingly, copper from the Levant—once thought to have been part of Sardinia’s bronze trade—played no role. Without osmium analysis, this detail would have remained invisible.

The findings, published in PLOS One, have reshaped our understanding of Sardinia’s place in the Bronze Age world.

Science Meets Archaeology

Behind these discoveries lies a story of collaboration. As Professor Helle Vandkilde of Aarhus University explains, archaeology provides the cultural and historical framework, while cutting-edge science refines and tests those interpretations. Together, they reveal insights neither discipline could reach alone.

For example, isotopic analysis did more than identify copper sources. It also uncovered evidence of strategic alloying. Sardinian bronzes were sometimes deliberately mixed from metals of different origins—not out of necessity, but to achieve certain qualities, such as stronger alloys or more striking colors. This hints at a sophisticated knowledge of metalworking and aesthetic choices deeply tied to cultural identity.

Even more intriguingly, when researchers examined bronzetti from three of the largest Nuraghic shrines, they discovered that the metals used across all sites were remarkably consistent. This suggests that Sardinia had a shared island-wide approach to bronze production, reflecting either centralized organization or a powerful cultural consensus.

The Mystery of Tin and Trade

Bronze, by definition, requires tin mixed with copper. Yet Sardinia, despite its mineral wealth, did not use its own tin or lead resources for the bronzetti. Instead, isotope signatures revealed that the tin used was imported from the Iberian Peninsula.

This detail opens a window into Bronze Age trade routes. Sardinia was not an isolated island but a vital hub within a vast network spanning the western Mediterranean. Tin, one of the most sought-after resources of the era, likely traveled through trade connections linking Iberia and Sardinia, feeding into the Nuraghe culture’s flourishing craftsmanship.

The reliance on imported tin underscores Sardinia’s importance: it was not only self-sufficient in copper but also well-positioned to participate in long-distance exchanges.

A Bridge Between the Mediterranean and the North

Perhaps the most fascinating revelation lies beyond Sardinia. Researchers have begun tracing stylistic and cultural links between the bronzetti and Nordic Bronze Age artifacts in Scandinavia, particularly in Denmark and Sweden.

The most striking connection is the appearance of horned helmets. In Sardinia, bronzetti depict warriors with dramatic horned headgear—an iconography that also appears in northern Europe. The famous Viksø helmets from Denmark, as well as petroglyphs in Tanum, Sweden, depict similarly adorned figures.

This is more than coincidence. Collaborative fieldwork between Aarhus University and Moesgaard Museum has shown that between 1000 and 800 BC, Sardinia and Scandinavia shared symbolic motifs. While direct contact remains debated, the parallels suggest that ideas, styles, and perhaps even objects traveled great distances along the Bronze Age trade networks.

Associate Professor Heide Wrobel Nørgaard notes that by studying where the bronzetti metals originated, researchers can now map Sardinia’s connections not just within the Mediterranean but all the way to northern Europe. The horned warrior motif serves as a cultural thread linking distant communities across thousands of kilometers.

The Human Story Behind the Metals

These scientific results are more than data—they reveal a human story. The Nuraghe people were not only skilled builders and metalworkers but also active participants in the grand web of Bronze Age exchange. Their bronzetti were not isolated creations but objects that carried the weight of cultural connections, ritual meanings, and technological sophistication.

Each figurine embodies not only copper from Sardinian soil but also tin from Iberian mines, knowledge passed through generations, and symbols that resonate from the Mediterranean to Scandinavia. They are small in size but monumental in meaning: tangible proof of a connected Bronze Age world.

Conclusion: Sardinia’s Place in the Bronze Age World

The Nuraghe culture of Sardinia, with its stone towers and mysterious bronzetti, has long fascinated archaeologists and historians. Thanks to advances in isotope science, we now know more about the origins of these bronze figures than ever before. The copper was mostly local, but the tin was imported, underscoring Sardinia’s role as a node in the Bronze Age trade networks.

More than that, the artistic and symbolic connections between Sardinia and northern Europe reveal that ideas, styles, and perhaps even beliefs traveled vast distances, binding together communities separated by seas and forests.

What began as a question about where copper came from has blossomed into a deeper story: one of human ingenuity, collaboration across disciplines, and the interconnectedness of ancient worlds. The bronzetti remind us that even in the Bronze Age, people lived in a world far more connected—and far more creative—than we might ever have imagined.

More information: Daniel Berger et al, Multiproxy analysis unwraps origin and fabrication biographies of Sardinian figurines: On the trail of metal-driven interaction and mixing practices in the early first millennium BCE, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0328268