It began not with fireworks, but with a quiet signal slipping through the data streams of a space telescope. Somewhere in the routine scanning of the X-ray sky, the Einstein Probe noticed something out of place. A brief, intense burst of X-rays had flared and faded, leaving behind a question mark where calm had been expected. The event was new, transient, and unfamiliar. Astronomers gave it a provisional name, EP J2322.1-0301, and set out to understand what they had just witnessed.

At first glance, the flare looked mysterious, the kind of fleeting cosmic event that often hints at something extreme or exotic. But as the investigation unfolded, the story turned into something more intimate and, in many ways, more fascinating: a nearby star, smaller and cooler than our sun, had briefly erupted with tremendous energy, reminding scientists that even ordinary stars can unleash extraordinary outbursts.

Meeting the Star Behind the Signal

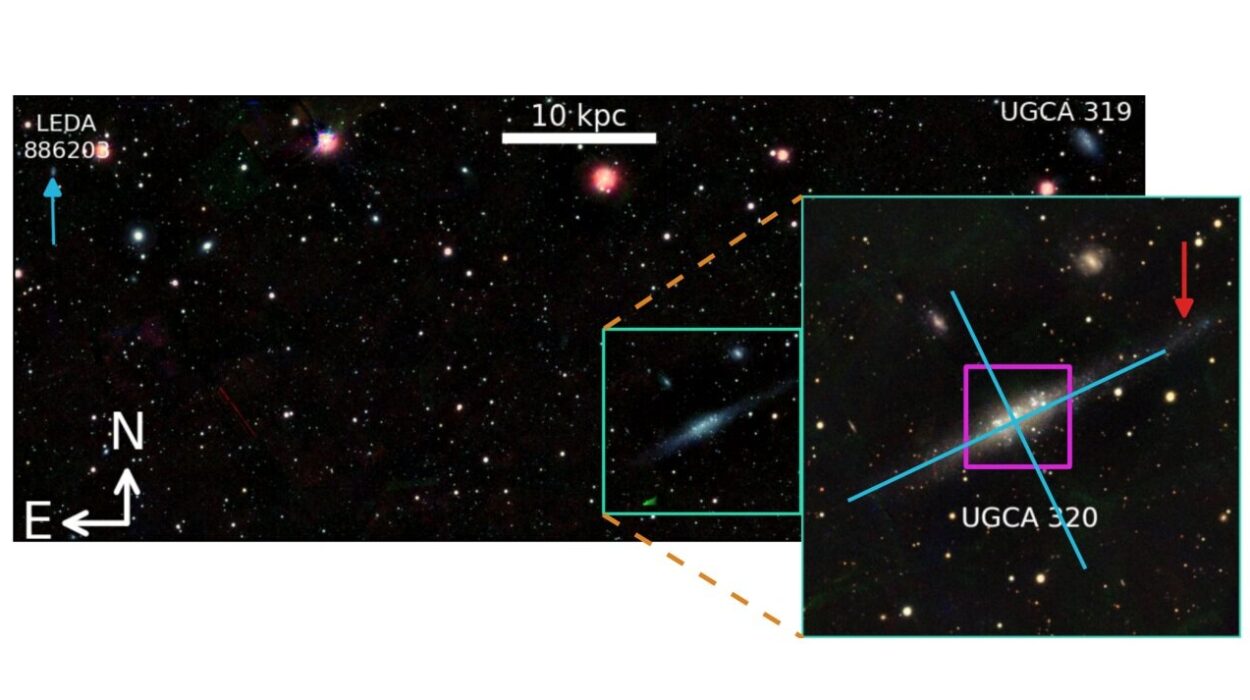

The source of the flare turned out to be PM J23221-0301, a K-type star located about 150.7 light years from Earth. Compared to our sun, it is more modest in size and mass, about 30% smaller and less massive, with an effective temperature of 4,055 K. Its age, estimated at around 1.2 billion years, places it firmly in the long, steady phase of stellar life, not the turbulent youth one might expect for dramatic eruptions.

This star was not entirely unknown to astronomers. Previous observations had already identified PM J23221-0301 as an X-ray source, albeit a quiet one, emitting what scientists call a quiescent flux. Optical monitoring had also revealed occasional episodes of brightening, subtle hints that the star was capable of brief moments of heightened activity. Those hints would soon prove crucial.

Why Astronomers Were Watching

Because PM J23221-0301 had shown signs of variability before, a team of astronomers led by Guoying Zhao of Sun Yat-Sen University in China decided to take a closer look. They organized observations using a combination of ground-based telescopes and space observatories, including the Einstein Probe. Their goal was not necessarily to catch a spectacular event, but to better understand the star’s behavior across different wavelengths.

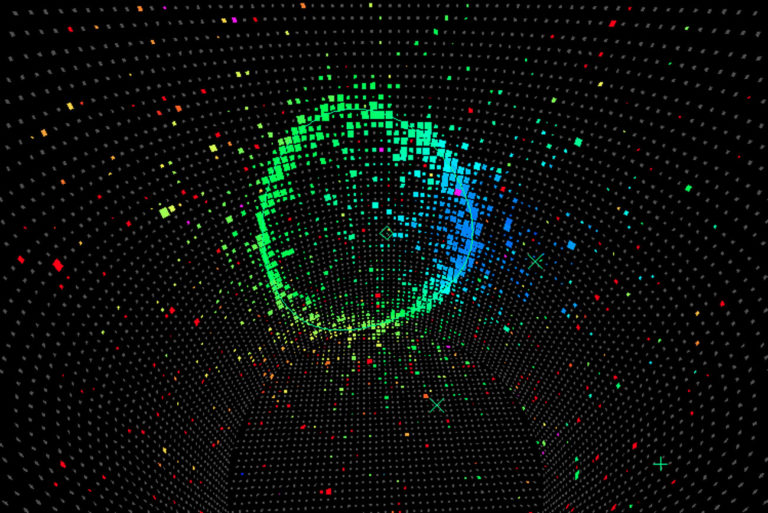

Then, in September 2024, the Einstein Probe delivered something unexpected. The data revealed an X-ray transient that lined up with the position of PM J23221-0301. The fleeting event, detected on September 27, stood out clearly against the background, demanding attention.

The researchers later summarized the moment in their paper, writing, “In this work, we present the discovery and multiwavelength characterization of the X-ray transient EP J2322.1-0301, discovered by the Einstein Probe on September 27, 2024. We identify it as a stellar flare from the high proper motion K-type star PM J23221-0301.”

Unmasking the Nature of the Flare

Once the transient was identified, the team worked through the evidence methodically. The first clue was spatial coincidence. The X-ray transient appeared within a 20-arcsecond position uncertainty of PM J23221-0301, close enough to strongly suggest a direct connection. But position alone was not enough.

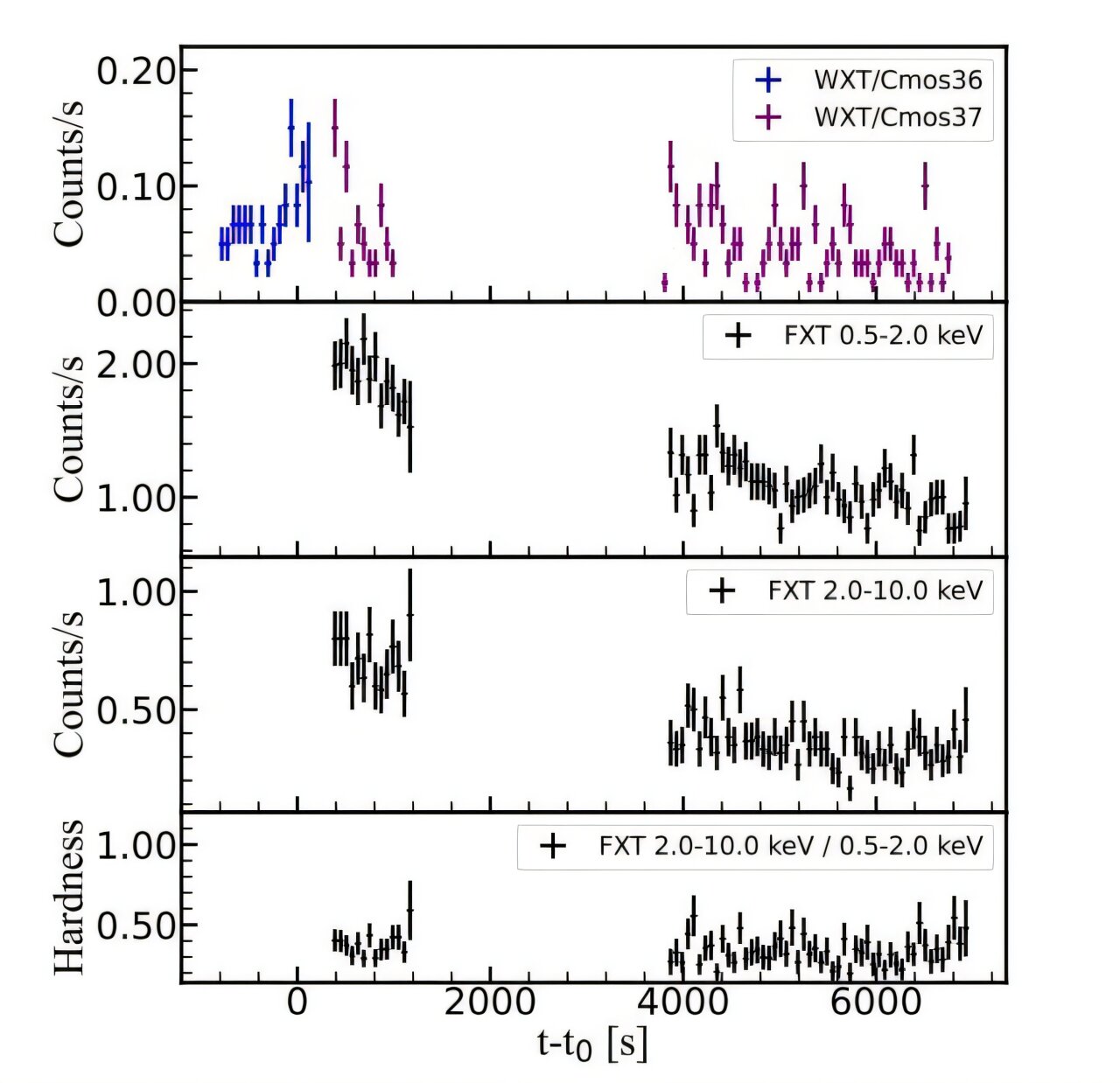

Next came the shape of the X-ray light curve. The flare rose quickly, peaked, and then faded more slowly, following what astronomers recognize as a fast-rise-exponential-decay, or FRED, profile. This pattern is a classic signature of stellar flares, events driven by sudden changes in a star’s magnetic field.

Additional confirmation arrived from optical observations. During the event, astronomers detected a transient hydrogen-alpha emission line in optical spectra, another hallmark of stellar flare activity. Finally, the overall energetics of the event matched what scientists already know about flares from stars like this one.

Taken together, these lines of evidence transformed the mysterious transient into something familiar and well-understood: a typical stellar flare, powerful but not unprecedented.

A Brief but Powerful Outburst

Although the flare was typical in nature, its scale was anything but trivial. The entire event lasted about two hours. The rise to peak brightness took approximately 0.4 hours, followed by a decay phase lasting around 1.6 hours. These timescales fit neatly within the range reported by other studies of stellar flares, reinforcing the conclusion that this was a standard, if energetic, eruption.

At its peak, the flare reached a luminosity of 13 nonillion erg per second in the 0.5–4.0 keV energy band. Over its full duration, it released an estimated total energy of 91 decillion ergs. These numbers are staggering by everyday standards, yet they fall squarely in line with measurements from other observed stellar flares.

Such events occur when shifts in a star’s magnetic field accelerate electrons to speeds approaching that of light. The energized particles then trigger eruptions that emit radiation across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to X-rays. For a brief moment, the star becomes dramatically brighter and more active, before settling back into its quieter state.

Layers of Heat in a Stellar Storm

One of the more intriguing aspects of the observation was what it revealed about the internal structure of the flare itself. The data showed evidence of a multitemperature plasma, suggesting that different regions of the flaring material were heated to different degrees. This hints at a stratified structure within the flare, rather than a single uniform burst of hot gas.

The astronomers interpreted this finding as consistent with standard flare-loop models. In these models, magnetic loops anchored in the star’s surface trap and guide plasma. During a flare, chromospheric evaporation drives hotter plasma into the upper regions of the loop, while cooler material remains at lower altitudes. The result is a layered, dynamic structure that evolves over the course of the event.

Seeing this pattern in PM J23221-0301 adds confidence that the physical processes driving stellar flares are robust and repeatable, even across stars that differ in size, age, and temperature.

From Mystery to Understanding

What began as an unidentified X-ray transient ended as a detailed portrait of a stellar flare unfolding on a nearby star. The journey from detection to explanation highlights how modern astronomy works, combining data from multiple wavelengths and instruments to piece together a coherent story.

The Einstein Probe played a central role, acting as an early warning system that flagged the transient in real time. Follow-up observations and careful analysis then filled in the details, turning a fleeting signal into a meaningful scientific result.

In the end, EP J2322.1-0301 was not a sign of something unknown or alarming. It was a reminder that stars, even relatively ordinary ones, are dynamic and occasionally dramatic objects.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it deepens our understanding of stellar behavior, especially for stars that are smaller and cooler than the sun. By confirming that PM J23221-0301 produces flares with familiar timescales, energetics, and internal structure, astronomers strengthen the broader picture of how magnetic activity operates across different types of stars.

The discovery also demonstrates the power of wide-field X-ray monitoring. The ability to catch transient events as they happen allows scientists to study short-lived phenomena that might otherwise be missed. Each detected flare becomes a natural laboratory, offering insight into magnetic fields, plasma physics, and energy release under extreme conditions.

Most importantly, this work reminds us that the universe is not static. Even stars that seem quiet and unremarkable can surprise us with sudden flashes of intensity. By paying attention to those moments, astronomers continue to uncover the subtle rhythms of stellar life, turning brief sparks of light into lasting knowledge about how stars, including our own sun, behave and evolve.

More information: Guoying Zhao et al, Einstein Probe Discovery of an X-ray Flare from K-type Star PM J23221-0301, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2512.16679