On any clear night far from city lights, the sky appears as a vast black dome punctured by countless stars. The darkness feels natural, even comforting, as though night itself were an obvious and inevitable feature of the universe. Yet this apparent simplicity conceals one of the most profound puzzles in the history of science. If the universe is filled with stars and galaxies extending in all directions, why is the night sky dark at all? Why is it not ablaze with light in every direction, glowing as brightly as the surface of a star?

This question, deceptively simple and deeply unsettling, lies at the heart of what is known as Olbers’ Paradox. It is not a paradox in the sense of a logical trick or wordplay, but a genuine conflict between reasonable assumptions about the universe and the stark reality we observe. The darkness of the night sky becomes, under careful thought, a clue pointing toward the true nature of the cosmos: its history, its structure, and its evolution.

The story of this paradox is not only about stars and light, but about humanity’s growing understanding of time, space, and the limits of the observable universe. It is a story in which darkness speaks louder than light.

The Intuitive Expectation of a Bright Sky

To appreciate why the darkness of the night sky is puzzling, one must begin with a simple and intuitive line of reasoning. Imagine a universe that is infinite in size, filled uniformly with stars similar to the Sun. In such a universe, every direction you look should eventually end at the surface of a star. Even if a star is extremely distant, there should be another star behind it, and another behind that, extending endlessly into space.

In this picture, distance alone does not eliminate light. While individual stars become fainter as they are farther away, the number of stars increases with distance. For every shell of space you consider, farther shells contain more stars, and their combined light should compensate for their greater distance. The result, according to this reasoning, is unavoidable: the sky should be uniformly bright, with no true darkness anywhere.

This expectation was not merely philosophical speculation. It followed directly from classical physics and geometry. Light travels in straight lines, stars shine continuously, and space is assumed to be eternal and unchanging. Under these assumptions, darkness becomes the anomaly, not brightness. The blackness of the night sky stands in direct contradiction to what logic seems to demand.

Early Reflections on the Dark Sky

Long before the paradox was formally named, thinkers had noticed the problem. Johannes Kepler, writing in the early seventeenth century, wondered why the sky was dark if the universe contained countless stars. He suggested that the universe might be finite in size, with stars occupying only a limited region of space. This idea was radical at the time, challenging the prevailing belief in an infinite cosmos.

Other thinkers proposed different explanations. Some suggested that interstellar dust might absorb starlight before it reaches Earth. Others speculated that stars might not shine forever, eventually burning out and leaving dark regions behind. These ideas reflected genuine attempts to reconcile observation with theory, even though they were incomplete or flawed by modern standards.

The paradox took its name from the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers, who discussed the problem in the early nineteenth century. Olbers himself proposed that dust scattered throughout space might block light from distant stars. However, this explanation contained a fatal flaw. Any dust that absorbs light would eventually heat up and re-radiate that energy, glowing until it became just as bright as the stars themselves. Dust could not hide an infinite number of stars forever.

The persistence of the paradox signaled that something more fundamental was wrong with the assumptions underlying the classical picture of the universe.

Light, Distance, and the Geometry of Space

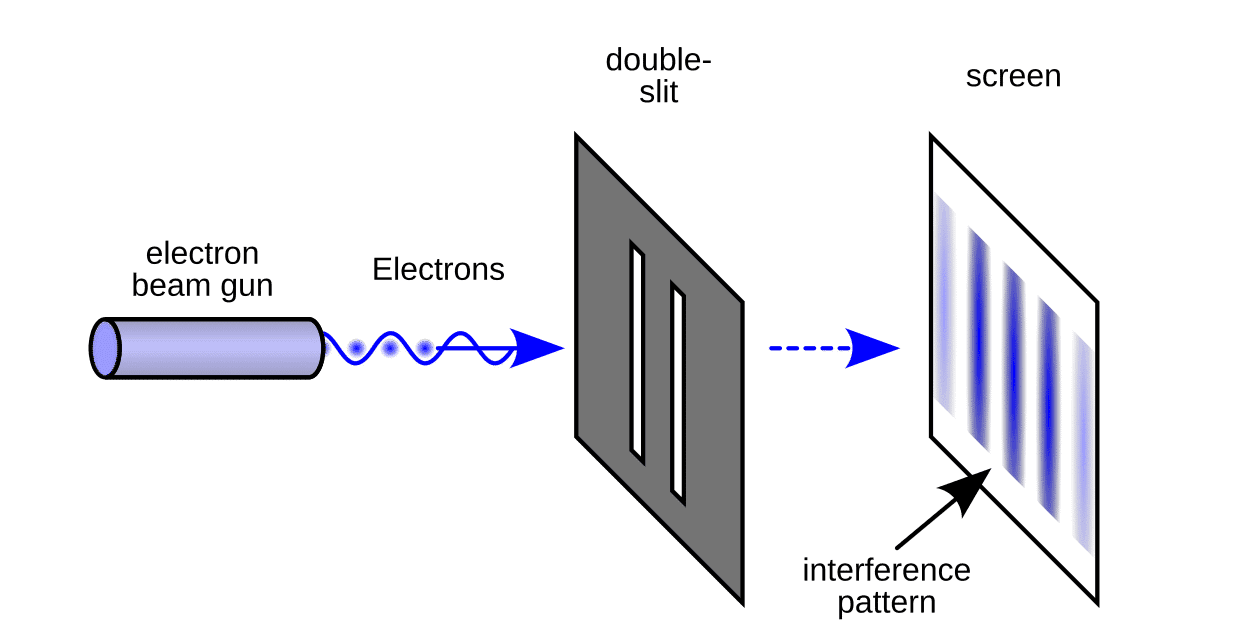

At the core of Olbers’ Paradox lies a subtle interplay between geometry and physics. As distance increases, the brightness of an individual star decreases according to the inverse square law. Double the distance, and the light spreads over four times the area, reducing brightness to one quarter. At first glance, this seems to solve the problem of distant stars contributing little light.

However, geometry intervenes. The number of stars within a given distance increases with the volume of space, which grows as the cube of the distance. When considering thin spherical shells at increasing radii, the number of stars in each shell increases as the square of the distance, exactly compensating for the inverse square dimming of individual stars. Each shell, regardless of its distance, contributes roughly the same amount of light.

This elegant but troubling result implies that the total brightness of the sky should diverge, becoming infinitely bright if the universe is infinite, eternal, and uniformly filled with stars. The fact that it does not forces us to question one or more of these assumptions.

The Finite Age of Stars

One possible resolution to the paradox lies in the lifetimes of stars. Stars are not eternal beacons; they are born, evolve, and eventually die. The Sun, for example, has been shining for billions of years, but it will not shine forever. If stars have finite lifespans, then perhaps the universe has not existed long enough for light from all possible stars to reach us.

This idea introduces time as a crucial factor. Light travels at a finite speed, and the universe may have a finite age. If the universe began at a specific moment in the past, then there is a limit to how far light could have traveled since that beginning. Regions of space beyond this cosmic horizon would be invisible to us, not because they do not exist, but because their light has not yet arrived.

This realization transforms the paradox. The darkness of the night sky becomes evidence that the universe is not eternal in the classical sense. Instead, it suggests a dynamic cosmos with a beginning, a history, and an evolving structure.

The Expanding Universe and the Redshift of Light

The discovery that the universe is expanding added another crucial piece to the puzzle. In the early twentieth century, observations revealed that distant galaxies are moving away from us, with their light stretched to longer wavelengths in a phenomenon known as redshift. This stretching reduces the energy of the light we receive, making distant objects appear dimmer than they would in a static universe.

In an expanding universe, space itself is growing, carrying galaxies apart and diluting the energy of the light they emit. This effect compounds the simple dimming due to distance. Light from extremely distant sources is not only faint because it has spread out, but also because its wavelength has been stretched by the expansion of space.

As a result, even if there are vast numbers of stars and galaxies, their combined light does not overwhelm the night sky. Much of it is shifted into wavelengths invisible to the human eye, such as infrared or microwave radiation. The darkness we see is not an absence of light altogether, but an absence of visible light.

The Cosmic Microwave Background as a Remnant Glow

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence supporting this modern understanding of Olbers’ Paradox is the cosmic microwave background radiation. This faint, uniform glow fills the universe and represents the afterglow of the hot, dense state from which the cosmos emerged. It is the oldest light we can observe, dating back to a time when the universe became transparent to radiation.

The cosmic microwave background demonstrates that the universe is not dark in an absolute sense. It is filled with radiation, but that radiation has been stretched by cosmic expansion into microwave wavelengths, far beyond human vision. If our eyes were sensitive to microwaves instead of visible light, the sky would appear uniformly bright in all directions.

In this way, Olbers’ Paradox is not so much solved as reinterpreted. The night sky is dark because the universe has evolved, and the light that fills it has changed character over time.

The Role of Galaxy Formation and Structure

Another important factor in resolving the paradox is the non-uniform distribution of matter in the universe. Stars are not evenly spread throughout space. They are grouped into galaxies, which themselves are arranged into clusters and vast filamentary structures separated by enormous voids. This large-scale structure means that many lines of sight do not end at the surface of a star or even a galaxy.

The universe is not a continuous sea of starlight, but a complex cosmic web. The spaces between galaxies are vast and relatively empty, allowing darkness to persist. While this factor alone does not fully resolve the paradox under classical assumptions, it contributes to the overall picture of a universe in which light is not uniformly distributed.

Moreover, star formation itself is not constant over time. The rate at which stars form has changed throughout cosmic history, peaking billions of years ago and declining since then. This temporal variation further limits the amount of light available to fill the night sky.

Energy Conservation and the Fate of Light

Classical attempts to resolve Olbers’ Paradox often stumbled over misunderstandings of energy conservation. If light from distant stars were absorbed by matter, that matter would heat up and re-emit radiation, eventually glowing just as brightly. This reasoning remains valid, but it assumes a static universe.

In an expanding universe, energy conservation takes on a more subtle form. As space expands, the wavelength of light stretches, reducing its energy without transferring that energy to matter. This cosmological redshift allows light to fade without heating the universe indefinitely. The expansion of space itself provides a mechanism for diminishing the brightness of distant light sources.

This insight highlights the deep connection between cosmology and fundamental physics. The resolution of Olbers’ Paradox depends not only on astronomy, but on our understanding of spacetime, energy, and the laws governing the universe as a whole.

Darkness as Evidence, Not Absence

It is tempting to think of darkness as emptiness or nothingness, but in cosmology, darkness is often rich with meaning. The dark night sky is a record of the universe’s history, encoded in the absence of overwhelming brightness. It tells us that the universe had a beginning, that it has been expanding, and that its contents are finite in age and energy output.

Every dark patch between stars is a reminder that we are looking out into a cosmos with limits, horizons, and an evolving structure. The darkness does not contradict the existence of countless stars and galaxies; it confirms the dynamic nature of their existence.

In this sense, Olbers’ Paradox transforms from a problem into a powerful diagnostic tool. It forces us to confront our assumptions and refine our models, guiding us toward a more accurate picture of reality.

The Emotional Power of a Dark Sky

Beyond its scientific significance, the darkness of the night sky carries emotional and philosophical weight. For countless generations, humans have looked up into the blackness and wondered about their place in the universe. The contrast between the vast dark expanse and the scattered points of light evokes both humility and curiosity.

If the sky were uniformly bright, the stars would lose their individuality, blending into a featureless glow. The darkness allows stars to stand out, to become landmarks and symbols. It enables the patterns of constellations, the navigation of travelers, and the poetic imagination of cultures around the world.

In a profound way, the darkness of the sky is what makes the light meaningful. It frames the stars, giving them context and depth, much as silence gives shape to music.

Olbers’ Paradox as a Turning Point in Cosmology

Historically, Olbers’ Paradox played an important role in challenging the idea of a static, eternal universe. It exposed the limitations of classical cosmology and hinted that time and evolution must be part of the cosmic story. Long before the Big Bang theory was formulated, the paradox suggested that the universe could not be infinitely old and unchanging.

As modern cosmology developed, the paradox found its resolution within a broader framework that includes cosmic expansion, finite age, and the evolution of matter and radiation. It became a striking example of how simple observations can have far-reaching implications when examined carefully.

In this way, Olbers’ Paradox exemplifies the power of physics to extract deep truths from everyday experiences. The night sky, familiar and unremarkable at first glance, becomes a gateway to understanding the origin and structure of the universe.

A Universe That Tells Its Story Through Light

Light is the primary messenger of cosmology. Every photon arriving at Earth carries information about its source and the journey it has taken through space and time. The darkness between those photons is equally informative, revealing the limits of what has had time to reach us and the transformations light has undergone.

When we look at the night sky, we are not seeing the universe as it is now, but as it was in the past. The farther we look, the deeper into cosmic history we peer. The darkness marks the boundary of our observable universe, beyond which light has not yet arrived or has been stretched beyond detectability.

This perspective turns the sky into a historical document, written in light and shadow. Olbers’ Paradox teaches us how to read that document correctly.

The Continuing Relevance of an Old Question

Although the basic resolution of Olbers’ Paradox is now well understood, the question it poses remains relevant. Modern research continues to explore the detailed history of star formation, the nature of cosmic expansion, and the behavior of light over vast distances. Each of these areas refines our understanding of why the night sky looks the way it does.

New observations, from powerful telescopes on Earth and in space, push the boundaries of the observable universe ever farther. As we detect fainter and more distant objects, we deepen our appreciation of the balance between light and darkness that defines the cosmos.

The paradox also serves as a reminder of the importance of questioning assumptions. What seems obvious may conceal deeper complexities, and even the most familiar experiences can challenge our understanding when examined closely.

Darkness, Light, and the Human Perspective

Ultimately, the question of why the night sky is dark connects scientific inquiry with human experience. It reminds us that our perceptions are shaped by the physical laws governing the universe, and that understanding those laws can transform how we see the world.

The darkness above us is not a void, but a consequence of cosmic history. It reflects a universe that began, evolved, and continues to change. In recognizing this, we see the night sky not as an empty backdrop, but as a dynamic and meaningful aspect of reality.

Olbers’ Paradox invites us to look at the familiar with fresh eyes, to find wonder in the ordinary, and to recognize that even silence and darkness can speak volumes about the nature of existence.